The UnSchool of Disruptive Design turns 9 years old this week! What an immense pleasure it’s been to create and share this experimental knowledge lab with tens of thousands of people from around the world over the last 9 years.

The Trap of Wishcycling

By Leyla Acaroglu, originally published on Medium

Image by Volodymyr Hryshchenko on UnSplash

Wishcycling is when people place non-recyclable items in the recycling and hope those items will end up being recycled. The unfortunate reality, though, is that these actions contaminate the recycling stream and reinforce the very problem of waste.

Wishcycling comes from a place of good intentions, but as we all know, good intentions do not always lead to good outcomes.

I think it’s safe to say everyone has done this at some stage.

We’ve popped the coffee cup into the recycling bin with some coffee still in it and the lid on, or that thin plastic wrapper, a pizza box, lightbulb, broken drinking glass, batteries, chopsticks, maybe even an extension cord (I’ve seen it happen), and hoped that it would go off and be magically made into some new thing.

Yet the truth is, we don’t have a magical recycling system where everything can be easily transformed into something new. In fact, most things you think are recyclable, are probably not. Recycling has not been able to keep up with the rapid changes to our hyper-disposable and complex material world. Yes, your uncoated paper, tin and aluminum cans, PET bottles, and a few other ridged plastic products can technically be recycled, but the vast majority of the packaging and products that end up in your home, can’t or won’t get a second life.

Waste collection systems all over the world are struggling with the diversity of material combinations of products and packaging. Coupled with the recent changes to the global recycling supply chain, we have an exponential waste crisis unfolding. The list of what not to include in your recycling (because it will end often up contaminating the entire load of recyclables and be destined for landfill or incineration, all at a cost to the recycling company) is long. It’s actually surprising just how many not-to-include items are on the list in some places. That’s because recycling is different everywhere, and because we have created a material world so complex, it’s hard for the waste processors to keep up with the diversity of ever-changing waste streams.

When modern recycling first became a regular curbside thing in the 70’s (in part to reduce the amount of waste filling up city landfills), the material world was very different. Originally it was just glass, metal and paper that were separated and collected. These had clear markets they could be sold back into, and so the economics of recycling was feasible. Then came combination products like tetra packs and chip packets (plastic and aluminum together), and a vast number of plastics. The diversity of new packages and household products started to really muddy the waters for the recyclers, and over time, most recycling moved to a single market — China.

Now we live in a material age where there are tens of thousands of different material and product combinations that enter homes the world over, and after a few decades of being told that recycling is great, we wishfully place many of them in the recycle bin, feeling good and hoping for the best.

Take, for example, the samples of packaging that I collected from different retailers in the UK. I found instructions, in small print on the back, mainly telling me that the products needed to be returned to the supermarket or were not recyclable at all. I was alarmed by how many packages (organic food products I might add) explicitly stated: “Do not recycle.” Nearly all of them were non-recyclable in my household collection system, yet a quick look in the shared recycling bin in my apartment block and it was overflowing with these very same un-recyclable materials.

The issue of greenwashing — misleading consumers into thinking something is green, or in this case recyclable, when it’s not — is a topic I have talked about in the past, and this certainly plays into the wishcycling issue. But it’s not as simple as all of us being manipulated or duped into thinking that everything with a recycling symbol is recyclable.

Many of us really do wish that things we buy can be recycled because it validates us buying them to begin with.

The people producing these types of packaging and products are very rarely thinking about the end-of-life issues that their material combination choices will have on a waste stream. They deflect responsibility onto us, the customers, and onto the city that will have to manage the plethora of produced waste from their poor designs. I also think it’s unfair that there is an expectation that the customer will be able to decipher the many different options for end-of-life management, for what appears to be the same types of materials, when they are not, as there are hundreds of different types of polymer combinations.

Equally, retailers don’t set adequate guidelines on what types of packaging they will accept in their products, so it becomes a free-for-all. Without shaming the specific brands or supermarkets, I can say that a quick walk up and down the isles of several UK supermarkets showed me that most of the packaging was un-recyclable. I’m going to guess this is the same in Australia, North American, China and most other major economies.

How can we, the customers, be responsible for not recycling when so much of what our food and hygiene products are designed into, is packaging that is not even collected in most cities? Here is a selection of packaging from fruit and nut packaging from major UK supermarkets, all non-recyclable. I wasn’t just cherry-picking these ether! Go look in your cupboards and see what is actually recyclable, and what is most likely not.

Plastics are particularly problematic as they are not easily recycled. Whilst the industry invested 50 million dollars a year to convince us that a number inside a triangle stamped on the base of a piece of plastic will mean that the product will be recycled, the likelihood of it being turned into something new will depend on many different factors, such as: if it’s even technically possible to recycle it (often not); how contaminated with food or product it is; if the local council will collect it; if the local municipal waste processing facility will take it; and if there is a market for that type of plastic to be sold into. Oh, and if there is a market for that plastic to be made into new plastic products. The oil and plastics industry has long known that it’s cheaper and easier to just turn virgin oil into new plastic than it is to collect, clean and resell it. They have profited off us believing that recycling is the solution when they have long known it is not.

This all leads to much confusion about what can and can’t be recycled, which unfortunately leads to people’s wishcycling, which then goes on to contaminate recycling streams all over the world, and then we get blamed for it! Education alone will not fix an inherently broken system.

Mainstream curbside recycling has been around for just over thirty years, and it’s in the last fifteen years that half of all the plastic that has ever been produced has been made and sold. To add to this, more than 90% of plastic ever produced hasn’t been recycled. Not because we consumers do the wrong thing, but because most of it is not easily recyclable!

The Recycling Industry

The margins on recycling are already very thin, with the collections and sorting often being more expensive than the value of the products being recycled. Some recycling processors still use human line sorters, and others are entirely mechanical. The machines that sort waste are often engineered for the main types of recyclables, such as glass, metal and hard plastics, not the plethora of other stuff that ends up in the sorting lines.

Then, even after the products are all sorted out and bailed up, the waste processing company has to find a buyer for that specific waste stream. Metals usually have a healthy demand, and thanks to the rise in online shopping, the paper board industry is doing ok. But plastics have always struggled to find a place to go (all the more reason to focus on post disposable design).

We wishcycle in part because we have been told that recycling is great and it will solve the issue of waste (this the plastics industry did a great job of convincing us of in the 90s, by creating the numbers up to 7 inside triangles that get stuck on certain types of hard plastics to supposedly help everyone identify and recycle them — side note, the history of the design of the original recycling symbol, the triangle made out of arrows, the Mobius Symbol, is fascinating and well worth the read here in this article.).

I have explained in the past that the global recycling system is broken, and that recycling is part of driving the generation of waste. It legitimizes the production of waste and creates a false solution to a manufactured problem. But here in this article, I want to explore the phenomenon that results from confused, good-intentioned, or perhaps lazy people that don’t know what to do with certain types of waste.

I will be the first to admit that even I am one of them at times. Intrigued by how others experienced this, I asked the UnSchool team to do a quick snapshot assessment of food items in their houses. As can be seen from the image below, it’s all very confusing about what the symbols mean. The cross through the recycling symbol means it can’t be recycled, but should we be happy that these ones even have any instructions at all? Because many of the other items they found had no information stating whether it was or wasn’t recyclable. This begs the question, whose responsibility is this? Ours, the supermarkets’, the local council, the recycling companies’, the packaging designers’, the product owners’? The federal government’s?

With such a confusing mess, it’s no wonder people wishcycle!

As I explored these issues, I come to feel very sorry for the recycling sector; they are beholden to the decisions made by the producers of products and packaging, and to the lack of regulation or guidance from the government. Then they’re burdened with the responsibility of finding new homes for an ever-growing stream of disposable stuff made with little care for what its end-of-life destination or impact will be.

How big is the wishcycling issue?

The less sexy name for the issue of wishcycling is recycling contamination, and in wealthy countries like the UK, Australia and the US, it’s a massive issue.

According to the UK Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), in 2018, contamination meant councils in the UK sent 500,000 tonnes of recycling to landfill. Research conducted by WRAP revealed that 82% of households in the UK add at least one item to their recycling that is not accepted. The amount of plastic packaging used in supermarkets in the UK is staggering. In 2017, the 10 biggest UK retailers produced 900,000 tonnes of packaging and 2bn plastic bags.

“More than two-thirds of consumers (69%) believe supermarkets and retailers are responsible for reducing the amount of plastic used, and many want to see more progress.” — Packaging News, 2021

In the US, the recycling system is increasingly under pressure. The EPA explains the conundrum of recycling: “Most Americans want to recycle, as they believe recycling provides an opportunity for them to be responsible caretakers of the Earth. However, it can be difficult for consumers to understand what materials can be recycled, how materials can be recycled, and where to recycle different materials. This confusion often leads to placing recyclables in the trash or throwing trash in the recycling bin.”

All over the US, recycling with no market to sell to, or place to store it is being burnt or sent to landfill. Increasing costs of processing have meant that some councils have just stopped collecting recycling altogether. This analysis shows how different states are working to address the issues with recycling in the US.

“Since 1960 the amount of municipal waste being collected in America has nearly tripled, reaching 245m tonnes in 2005. According to European Union statistics, the amount of municipal waste produced in western Europe increased by 23% between 1995 and 2003, to reach 577kg per person.” — The Economist

In Australia, a country where over 60% of people recycle, it was reported recently that 58% of plastic and 23% of glass packaging were put in the wrong bin. This is contributing to ongoing issues with contaminated exports to neighboring countries, where over 50% of recycling is sent to be processed.

To add insult to injury, Reuters reported last year that the oil industry plans on investing 400 billion dollars on plants to make new plastics and just 2 billion on reducing plastic waste. Wishcycling is only going to get worse.

Addicted to Disposability

The issues of wishcycling go deeper than just misunderstanding what is and isn’t actually recyclable. It speaks to a wider issue of waste and our relationship to it — specifically, how planned obsolescence and enforced disposability feed our addiction. To justify consumption, we need to believe that there is a better destination for our waste than just landfills, incineration or escaping into nature. We want it to be ok to create it, and as our material lives have become more disposable, more complex, there is a higher desire for the idea of recycling to work.

All over the world, the amount of municipal solid waste being generating is growing at unprecedented rates. In India, in 2001 it was 36.5 million metric tonnes, twenty years later in 2021, it’s now 110 million metric tons. This is estimated to grow to 200 million metric tons by 2041 (source, statistia).

“China is responsible for the largest share of global municipal solid waste — at more than 15 percent. However, in terms of population the United States is the biggest producer of waste. The U.S. accounts for less than five percent of the global population, but produces roughly 12 percent of global MSW and is the biggest generator of MSW per capita.” — Global waste generation — statistics & facts, Statista, 2021

Recycling is not the solution to waste. The global increases in solid waste generation are happening at rates far, far greater than any recycling system can manage (except maybe Germany, which has policies that shift responsibility back onto the producer and Wales, which is the world's third-best recycler!).

Recycling doesn’t work because its existence incentivizes and legitimizes the creation of waste. Thus, as a solution to the global waste crisis, it does no more than temporarily mask the issue at hand. We live in a linear economy, a system that requires the production of waste for it to function. We designed an incentive system of growth that relies on continual consumption, which means we must make waste to perpetuate it. To solve the waste crisis, we need to redesign the entire system of materials and how they flow throughout the economy. And certainly, companies need to be held accountable for the things that they create and pump out into the world.

This is the biggest design challenge of our time. How do we redesign everything so it works better for all of us? How do we meet human needs without destroying the systems that sustain us? This is the topic of a book I’ve been working on for some time and the more I reflect on the changes that need to occur, the more I see that many of the solutions put in place (such as recycling) are actually reinforcing the problems and preventing us from reimagining the systems that created this issues to start with!

I find this a hard realization to voice, but under the current system, recycling is a key part of legitimizing the disposable economy we live in and thus we need to stop relying on recycling and demand a full redesign.

Recycling contamination. Photo by Vivianne Lemay on Unsplash.

Aspirational Recycling

Recently there were reports of UK recycling being dumped in Turkey after the recycling market took a huge hit from the China waste ban that started in 2018 (the rise in waste trafficking is a rabbit hole I will explore in another article).

This is where the wishcycling situation plays into a psychological bias we are all part of. It’s also called aspirational recycling, which feeds into the desires that people have to “do the right thing.” Here, we all want recycling to be the solution to our growing global waste crisis, so much so, that people are likely to recycle items that connect to their self-identity, such as the coffee cups or the take-out food containers, even if they have a suspicion that they are not recyclable (which cups are not, nor are black plastic take out containers). A Harvard Business Review article claims there is a bias whereby waste production is increased through the pre-knowledge that an item could be recycled, which leads to an increased use of disposable items. So we trick ourselves into using things that are non-recyclable by wishing that they were. This is the root cause of wishcycling.

We collectively rely on recycling as a crutch, allowing the potential of materials being reused to justify our continued consumption and use of disposable items.

Industry relies on this collective bias to continue to produce more and more non-recyclable stuff and feed into a collective misunderstanding of what is and isn’t recyclable. Confusion is a great tool for distraction. When known side effects (such as the millions of tons of plastics in the oceans) come to light — and even though there is a nonexistent recycling system for the billions of tons produced each year— they go back and blame it on us for not recycling properly!

Is Recycling Worth It? By NPR

Then there’s the issues of different rules in different places, and the persistent claims from industries that things are recyclable (even if they are not), along with the misinformation that recycling is somehow the silver bullet solution to the world’s waste crisis — it’s no wonder we’re so misdirected. We wishcycle because we have been told that recycling is the solution and we all want to do the right thing.

Our desire for things to be “greener” often makes us do un-green things. This is not really our fault though; we’ve all fallen victim to decades of marketing spin from industries addicted to disposability, saturated with ads that tell us that littering is the issue and recycling is the solution. The false answer to a manufactured problem is to believe that a simple act of separating our waste into that which can be recycled and that which will end up in the ground or being burnt will fix the myriad of environmental and social equity issues that waste creates.

Recycling may have a place in a well-designed circular economy, but it will not solve the problem created by our addiction to easy, convenient, disposable stuff. The only way we can stop waste is by designing it out of the system to start with and this requires us to redesign everything, the materials used, the way we create products through to the entire economic system that they work within.

Wishcycling is part of a fairytale that has been told to us over and over again, it says recycling is a good solution to a massive problem. It feeds into our collective delusions that disposability can be remedied by the same system that benefits from waste. This all adds up to confused good-intentioned people who put their broken Christmas lights and soiled diapers in the recycling and hope for the best. And an industry that then blames the customer for not getting it right.

Where did the wishcycling concept come from?

The term “wishcycling” first appeared around 2015 when journalist Eric Roper wrote about the waste industry’s rising challenge of dealing with new types of materials and polymers that were making their way into the recycling bins of households.

In an article, Roper interviewed Bill Keegan, who was the President of a waste and recycling firm DEM-CON, where he mentioned the idea of people wishing things would be recycled. Inspired by the concept, Roper wrote a follow-on piece the following week about the concept of wishcycling where he detailed how plastic bags and bowling balls, food sachets, and loose bottle caps were all contributing to recycling contamination.

In the article, Roper explains, “A number of materials in particular frequently show up at local processing facilities, causing problems for the complex machines that make curbside single-sort recycling possible. They ultimately end up comprising the ‘residual’ waste that facilities cannot recycle.”

Wishcycling on the news (on Fox news!)

According to the industry magazine Recycling Today, “there are five common curbside recycling contamination themes: tanglers (hoses, cords, clothes), film plastic (plastic wrap or bags), bagged things (garbage or recycling), hazardous material (propane tanks, needles/sharps) and a category that can be summed up as ‘yuck’ things that downgrade other materials and clog the system (food, liquids, diapers, etc.).”

To help address this, on a practical level, online tools like this can help keen people figure out what can and can’t go in their recycling right now. But let’s be honest, the average person is more likely to make a quick judgment based on assumptions, leading to wishcycling. I know in my case, I feel guilty when I put things in the normal waste bin, so I want to avoid it and hope that the oat milk tetra pack is indeed going to be recycled!

Commonly wishcycled items:

Paper coffee cups: They are lined with plastic and have polystyrene lids so are not easily recycled. These have to go in the trash, so get a reusable cup for your daily caffeine fix!

Paper take-out containers: They are also often lined with plastic and if not then contaminated with the oils and residues of the food, the best you could hope for is the unlined ones going directly in your home compost or organic waste collection.

Broken glasses and ceramics: Recycling facilities are usually high-tech places that use lasers and magnets to separate out the recyclables. But often there are humans working a line, and broken glass can’t be picked out by the machines — humans with hands have to separate them out.

Pizza boxes: Any food-contaminated paper product is hard to recycle because the fibers absorb the grease and thus make the recycling process harder. So they have to go in the general waste or if you have organic waste collection/composting then it should go in there.

Flexible and soft plastics: These are basically ALL your food plastic packages that are soft and flexible, such as crisp and candy wrappers, rice bags, nuts and loose lettuce bags. Anything that is flexible is unlikely to be recyclable in most mainstream waste recollection services. Some stores offer a takeback program if you are diligent enough to separate, collect and take them back to your store.

Any electronic item: 100% of these have to go in a dedicated electronic waste recycling collection service. They are filled with complex and often toxic materials and can even explode, so be sure to find out from your local council about collections and drop-offs for e-waste.

Light globes: Most light globes are made of several different materials and thus can’t be recycled through the normal collection and need to be taken to a specialty recycling drop-off location.

Any household item: Broken toys and old T-shirts are most likely not recyclable in your household collection. These need to be taken to a specific location or better still, repaired and resold.

What can we do about it?

Waste is produced as a result of consumption. So the first thing we can do is nip the issue in the bud by not buying the things that can’t be recycled to start with. Of course, it would be even better if the companies who produced unrecyclable crap stopped designing such items, and supermarkets and producers got together and figured out how to create more universal packaging solutions that dramatically reduced waste, to begin with. Ahh, that would be bloody brilliant. But in the meantime, whilst we all wait for some of the biggest companies in the world to catch up to the growing global demand for a circular economy (I’m looking at you Amazon), then we have to each take on the task of figuring out what is actually recyclable in our community and then be a bit more diligent about where it ends up.

I for one buy mostly from a local food producer who only sells local produce and delivers it in reusable boxes. When I do have to shop at the supermarket I try and take a bit of time to read the packaging (and I still get it wrong sometimes FYI). I compost all organic waste and include all light uncoated paper products and bio-based plastics in the compost drop-off point (this will be industrially processed so all the biodegradable packaging can go in it).

It can feel insignificant to take these small micro-steps against a tidal wave of waste, but our own actions are calculated up and used to influence the actions that industries take. Once they realize people are actively avoiding certain products, they will be forced to refect and hopefully change. Wherever we can flex our consumer power, we help shape the way new trends emerge through demand (oat milk, and vegan food options, for example, is a relatively new addition to grocery shelves for a reason!).

Wishcycling is a symptom of a much broader issue at play: we have designed a world addicted to waste and disposability. Until we break that cycle, we, as everyday people, will continue to have to navigate our way through the material complexity that is thrust upon us.

But as long as we believe the fairytale that recycling will solve our waste crises, then we will continue to enable industries to get away with creating more and more disposable, unsustainable and un-recyclable crap.

——————

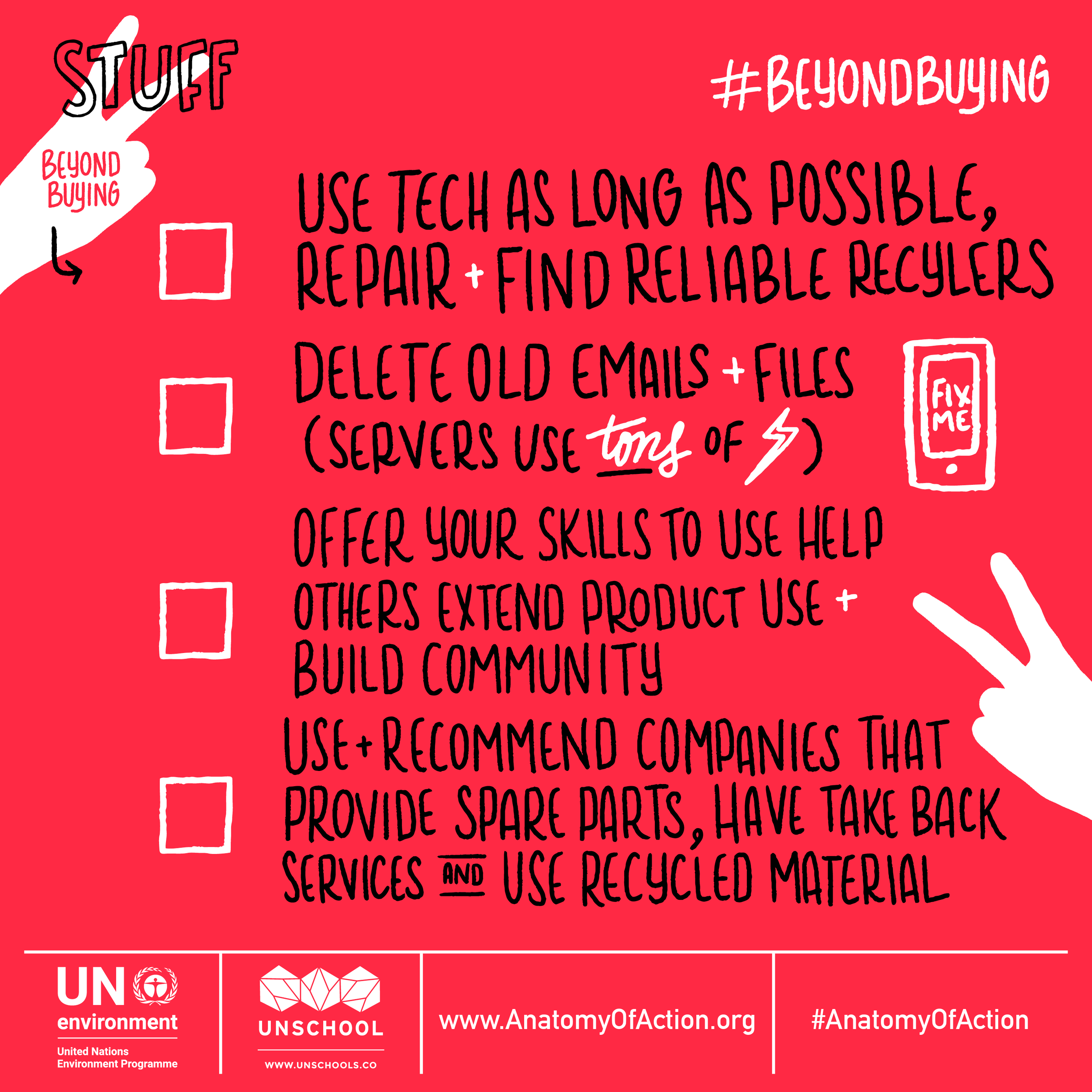

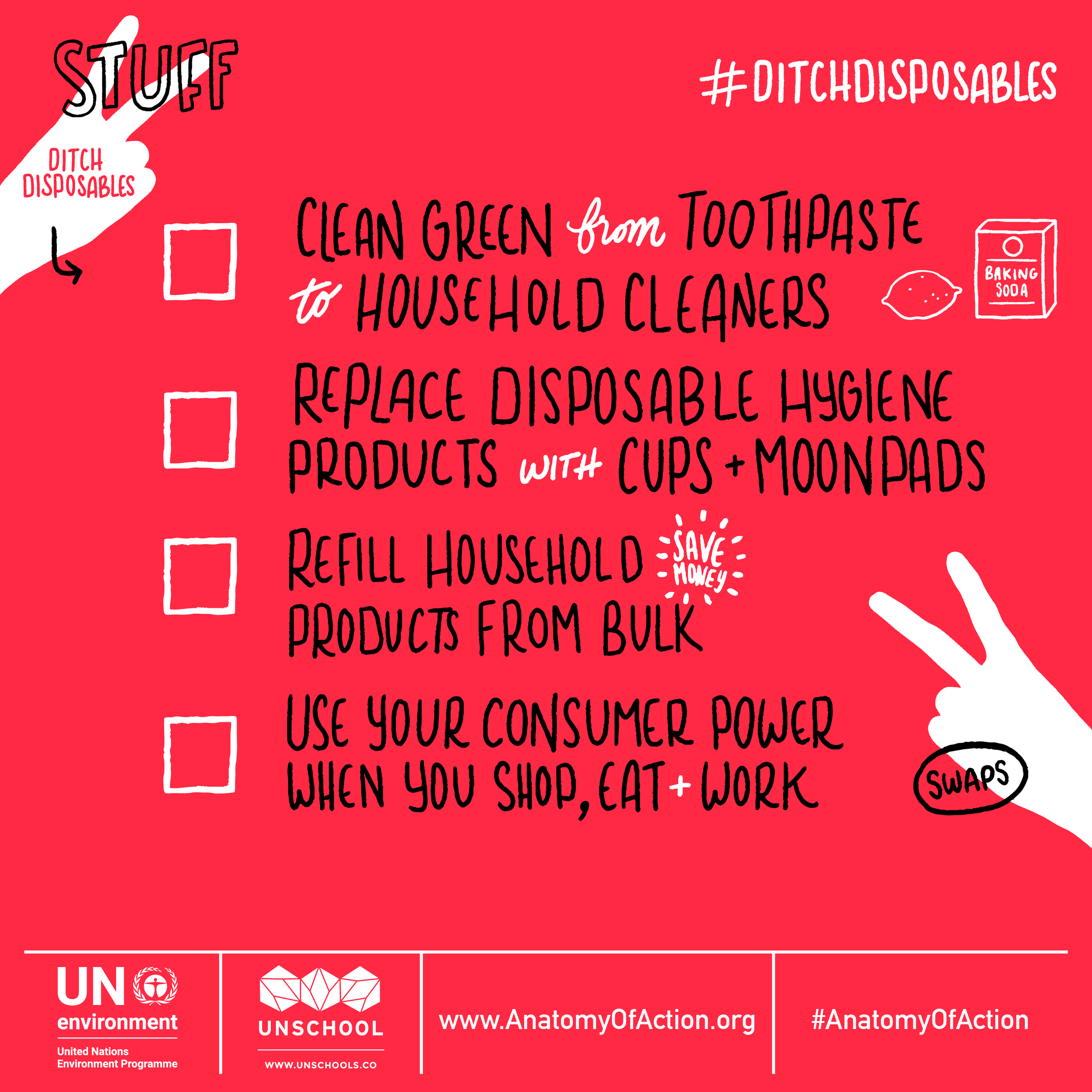

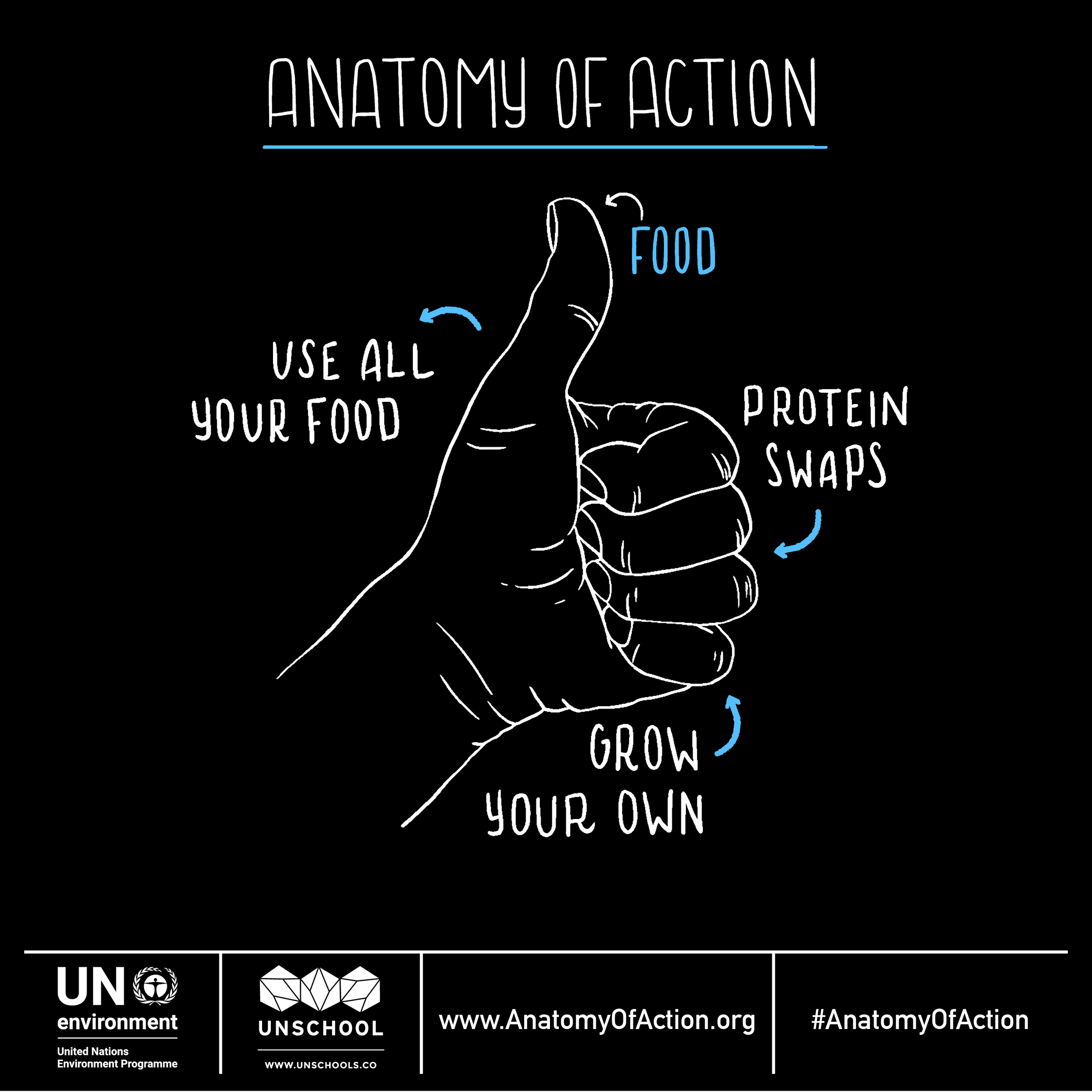

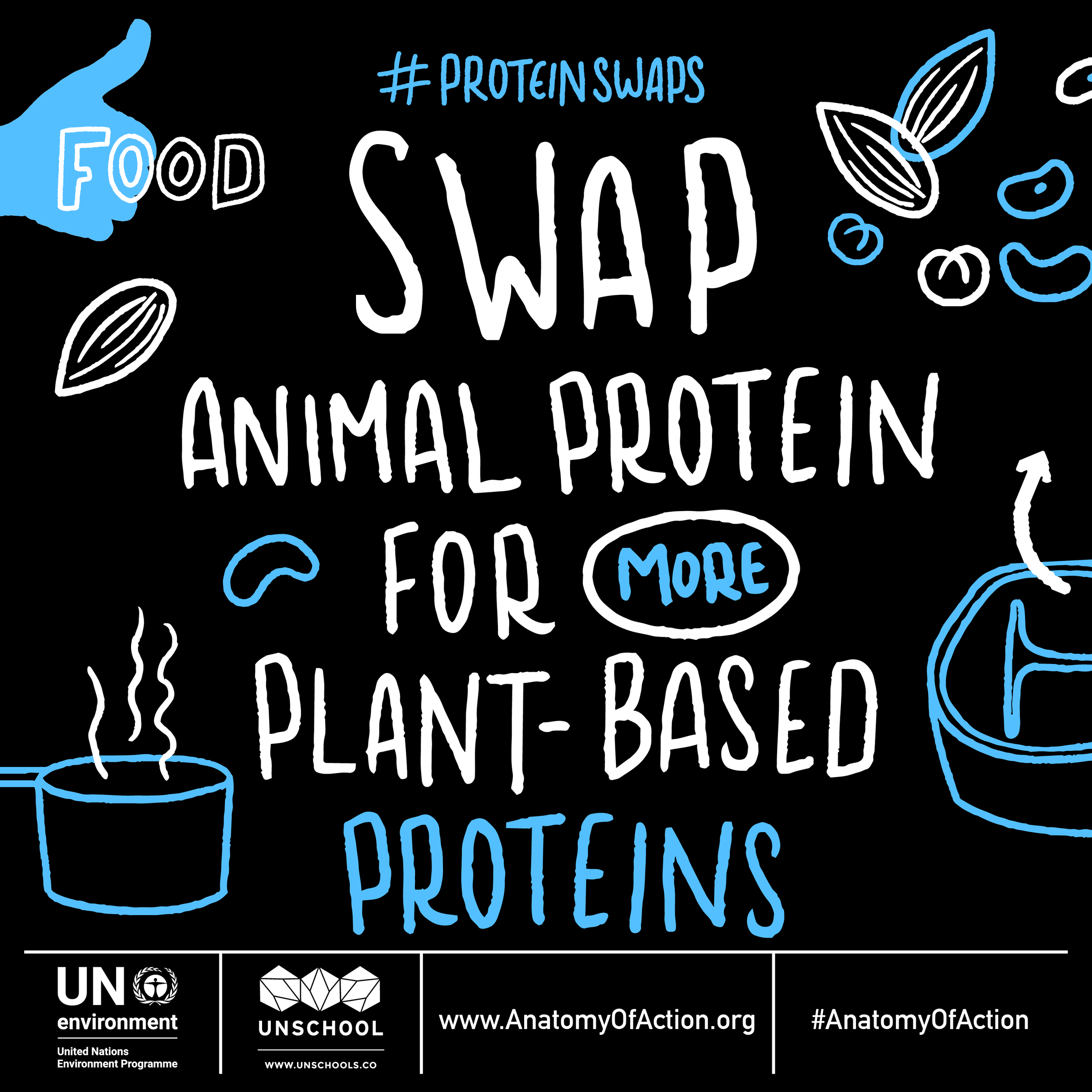

If you want to get started on your change-making journey, then check out my list of free tools for circular and sustainable design, or explore the everyday actions you can take via my United Nations collaboration, The Anatomy of Action.

The big opportunity for systemic change is in the way we do business, so I have courses on circular systems design, sustainable design, the circular economy and how to activate sustainability in business.

If you are interested in diving deeper into how to activate sustainability in any size business and want to help to bring about the transition to the circular economy, then consider signing up for my 2-day in-person Masterclass this October in London.

— -

Additional sources used in this article:

Rebecca Altma, Discard Studies, On Wishcycling, 2021, available here

Stephanie B. Borrelle, The Conversation, Recycling isn’t enough — the world’s plastic pollution crisis is only getting worse

Jackie Flynn Mogensen, 2019, Mother Jones, One Very Bad Habit Is Fueling the Global Recycling Meltdown

Erin Hassanzadeh, 2021, CBS Minnesota, Pandemic-Driven ‘Wishcycling’ Is Causing Big Problems At Recycling Centers

Drew Desilver, 2016, Pew Research Center, Perceptions and realities of recycling vary widely from place to place

Tom Mumford, 2020, ReCollect, Wishcycling 101: When Good Intentions Lead To Contamination

6 Focused Learning Categories to Boost your Change-Making Skills

Here at The UnSchool, there’s a handful of things that we never stop talking about: making positive creative change, embracing systems thinking, normalizing sustainability, igniting the circular economy, leveraging the Disruptive Design Method, and finally, diving into Cognitive Science by hacking our brains, mindsets and biases so that we can all expand our sphere of influence and active our agency to make massive sustainable changes to the way we live on this beautiful planet we all share!!!

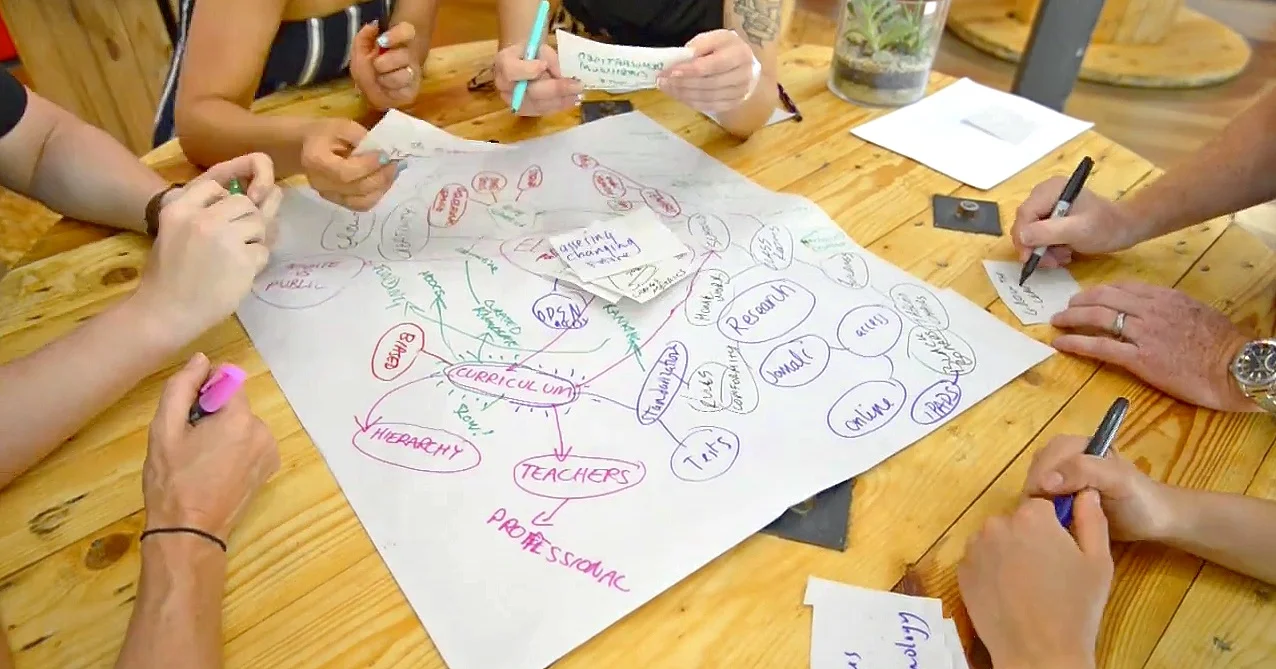

When we started this experimental knowledge lab in 2014, we did so with the intent to give others the tools they needed to disrupt the status quo and solve complex problems in order to make the future work better for us all. Now that we’ve been fully operational for almost 7 years, having transferred knowledge to thousands of change-makers like you all around the world, run fellowships in 10 countries (!), and created >80 offerings at UnSchool Online, we decided to organize our courses, toolkits and ebooks into the themed-knowledge areas that we focus on the most.

Our six brand new learning categories — Systems Thinking, Sustainability, Circular Economy, Creative Change, Disruptive Design, Cognitive Science — are designed to help you find what you need more efficiently and take a more targeted approach to refining your creative change-making skill set. Whether you are brand new to the world of making change or you’re a leader in creative change, we have offerings that can help you build your knowledge bank, refine your skillset, and amplify your impact. These new learning categories are simply like destinations on your change-making journey map, and we’ll step you through where to go based on where you are right now.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll spotlight each of the new learning categories here in our journal to help give you a better understanding of why these focused areas are so important not only to us — but for your work, too. Stay tuned!

PS: Speaking of knowledge transfer, have you browsed our recently upgraded Free Resource Library lately? It’s packed with brain-activating content (like Leyla’s Decade of Disruption report, or The Circular Classroom or Sustainability in Business!) and practical tools (like the Superpower Activation Kit, the Circular Redesign Kit, and our personal Post Disposable Kit!) that you can utilize right away.

Earth Overshoot Day & Your Ecological Footprint

Earth Overshoot Day

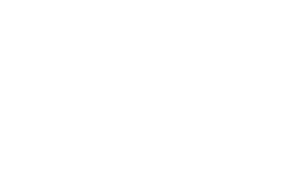

Every year the Global Footprint Network marks on the calendar a date that signifies the day we have collectively used up all the resources allocated for that year. It’s called Earth Overshoot Day, and in 2020, it falls on the 22nd of August. This is actually much better than 2019’s date, which was the 29th of July. This shift in a more sustainable direction is mainly due to the economic slow down as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Adapted from Earth Overshoot Day, last year we were a month behind this year.

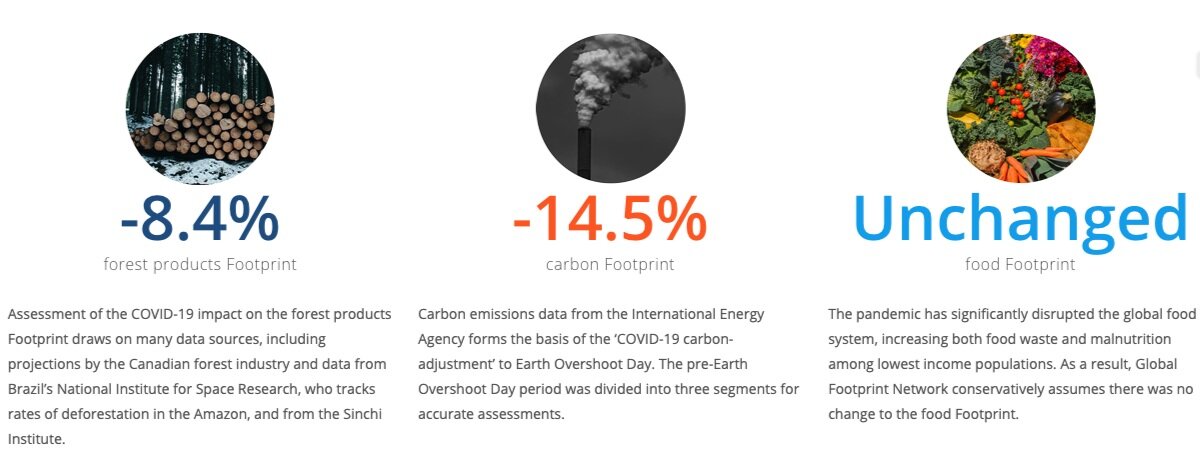

The Global Footprint Network combines the most reliable data available and forms a set of reasonable assumptions to assess the current resource use of humanity. They look at changes in carbon emissions, harvesting of forest products, food production and fossil fuel demand, along with other factors that have an impact on global biocapacity. The research team concluded that this year, as a result of the global pandemic, there has been a 9.3% reduction in the global Ecological Footprint compared to the same period last year, as reported on the Earth Overshoot Day website.

“The novel coronavirus pandemic has caused humanity’s ecological footprint to contract. However, true sustainability that allows all to thrive on Earth can only be achieved by design, not disaster.” - Earth Overshoot Day

The changes reported by the World Footprint Network as a result of changes to the economy from the Covid-19 pandemic

Your Ecological Footprint

Earth Overshoot Day brings awareness to one of the main issues that sustainability is seeking to address: we collectively consume more than the Earth can provide us with. Everything comes from nature, and the planet provides us with an abundance of resources, from minerals to shelter and food.

But since the early 1980s, we started to extract and use more resources at a rate faster than the Earth can replenish them each year. This means we are eating into future generations resources and creating a deficit. Thus we need to find creative ways of meeting our human needs, living prosperous lives, but whilst maintaining and respecting the life support systems that sustain life on Earth.

The ecological footprint methodology is a tool that helps individuals, cities, countries, and the entire world understand how big an impact they have on the one planet we all share. The eco footprint method looks at many 'impact categories', which are areas of our daily lives that have impacts on the planet and then provides a calculation of how many earths would be required if everyone lived your lifestyle. So the place you live, the types of things you consume - these all impact the size of your personal ecological footprint.

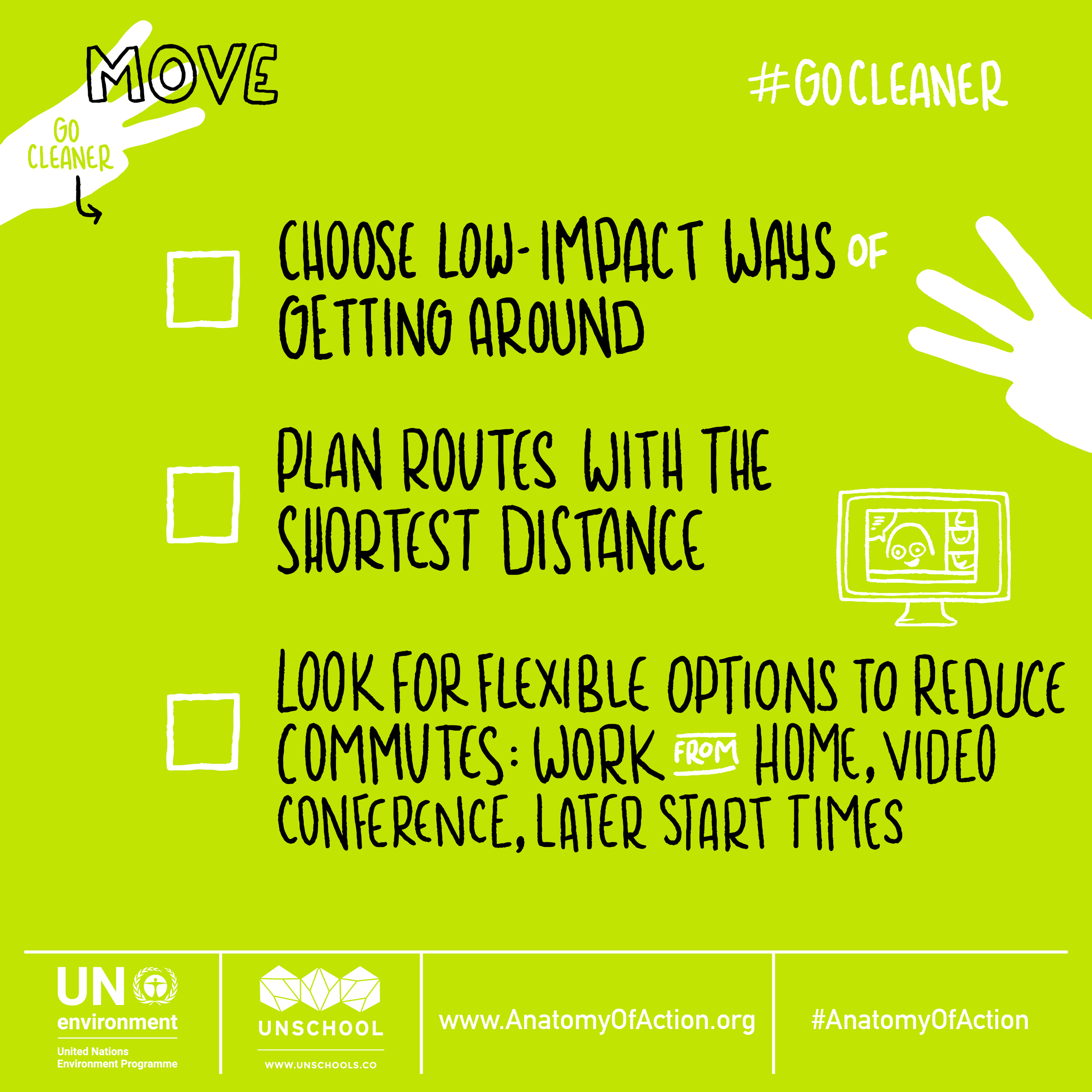

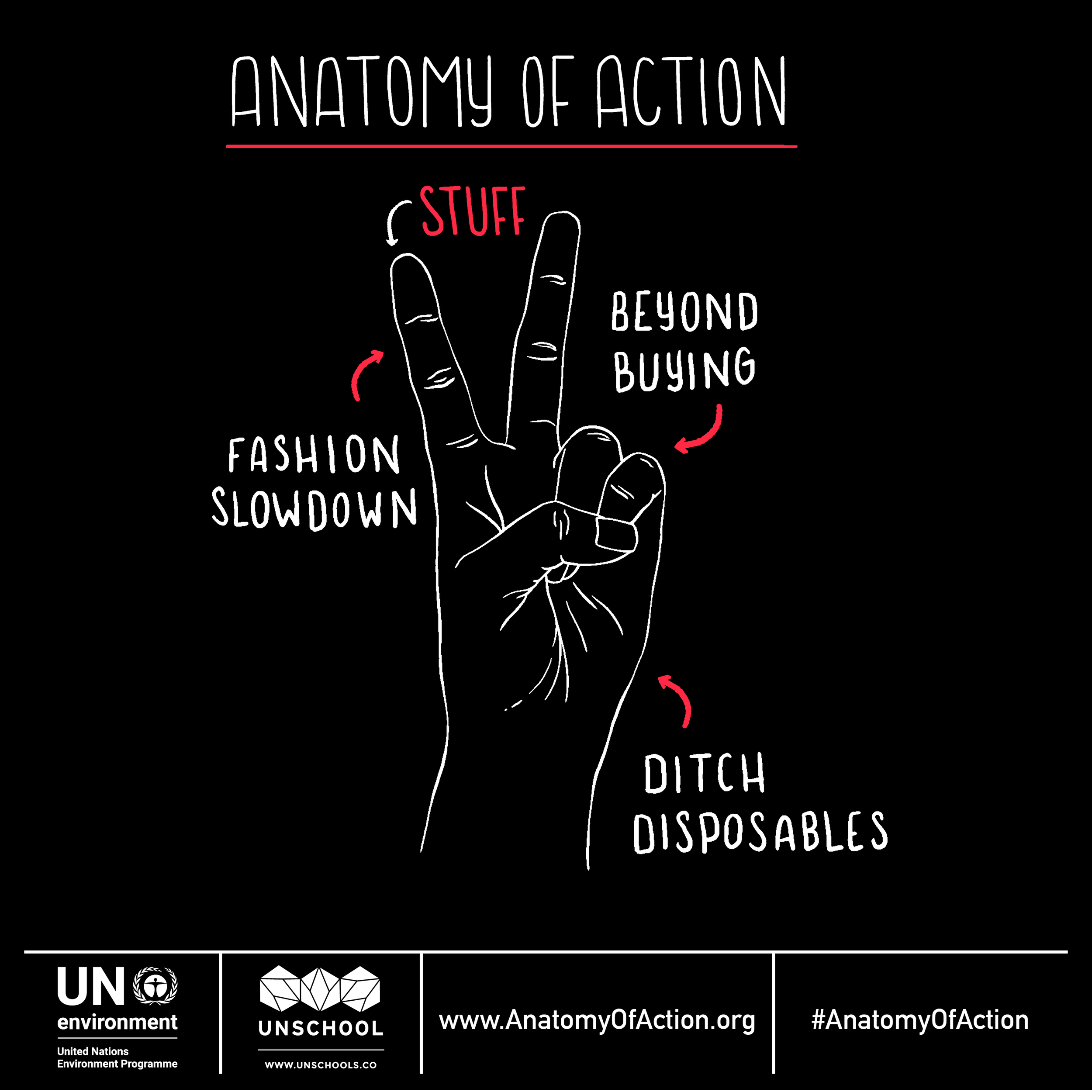

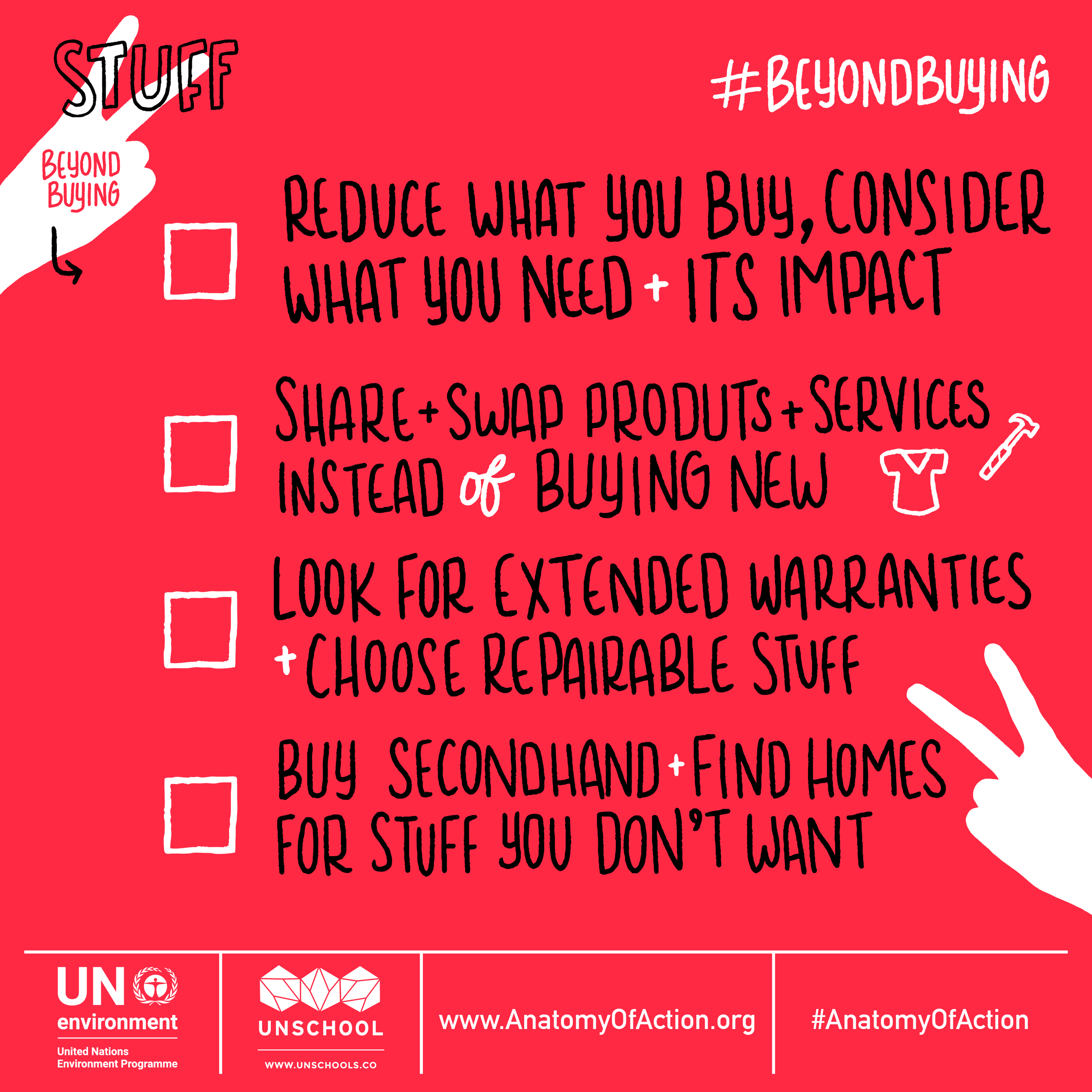

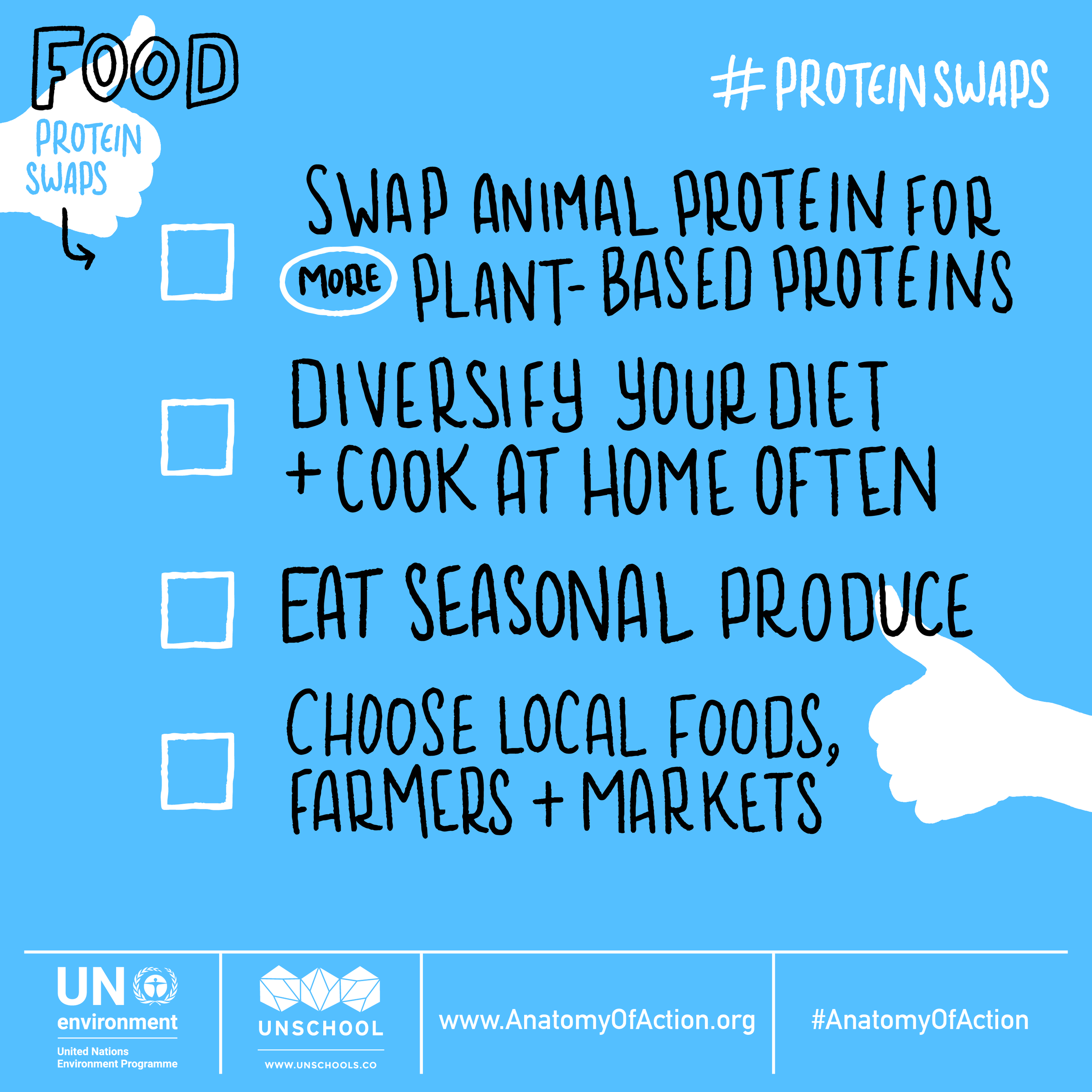

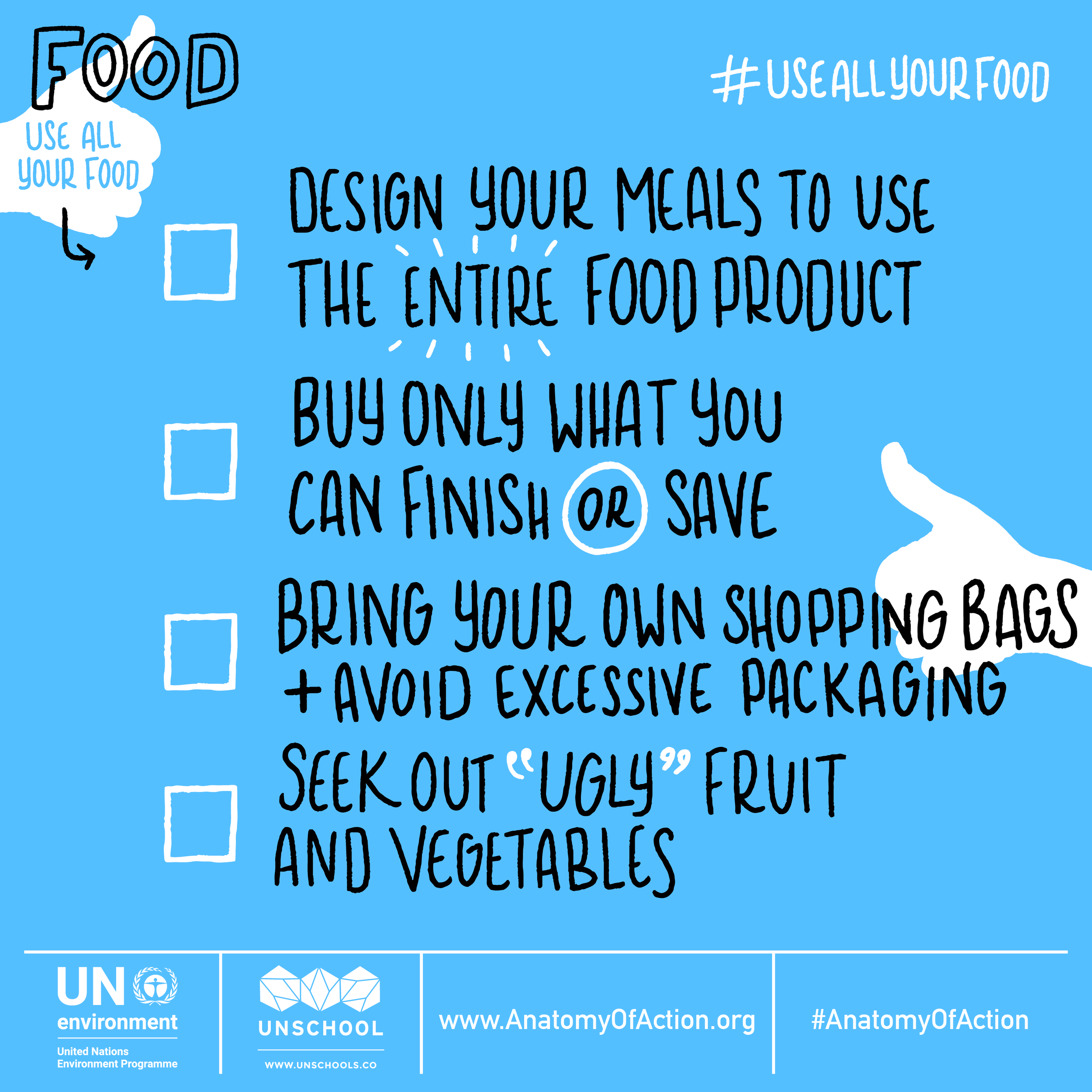

In part inspired by the ecological footprint concept, last year in collaboration with the United Nations Environment Programme, we came up with the Anatomy of Action - a set of actions everyone, anywhere, can take to live a more sustainable lifestyle. Using the hand as a memorable reference for the actions we each take in our lives, we can opt to reduce our footprint by making more effective lifestyle choices that reduce the impact of our actions.

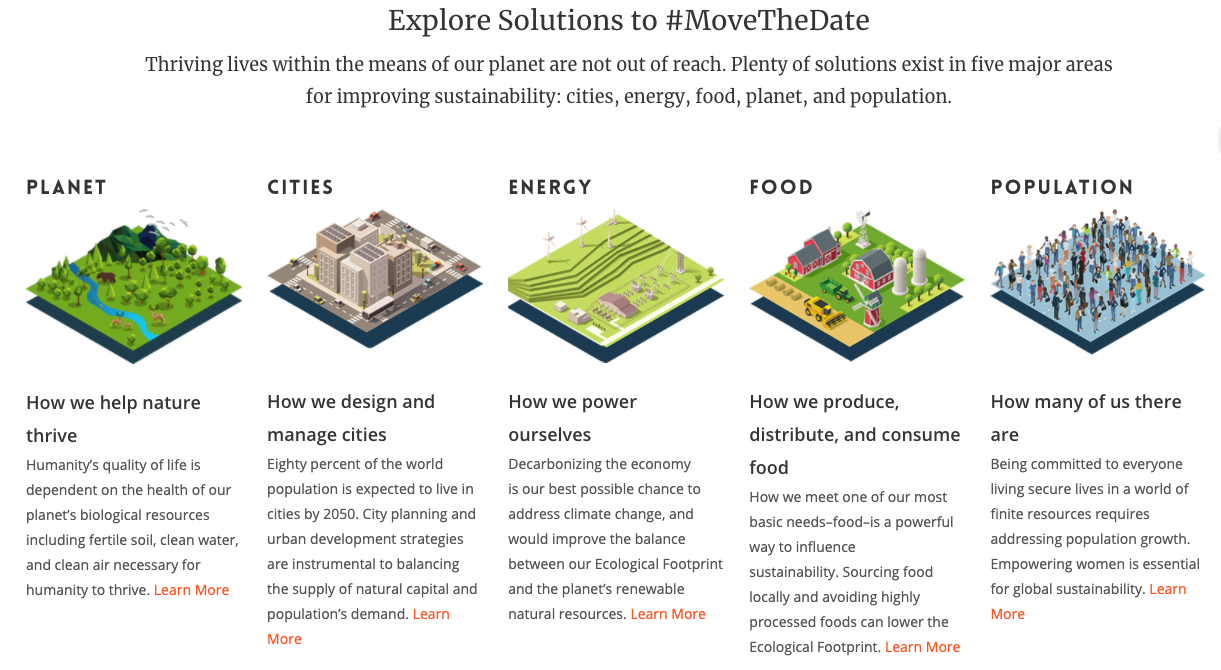

Move the date

Each year there is a campaign is to #movethedate for Earth Overshoot Day so we can get back in line with the Earth’s ability to sustain us. The last time this was the case was in the late 1970’s, so we need to collectively move the date back to December 31st, so that we are living within the carrying capacity of the planet.

In honor of Earth Overshoot Day, we challenge you to measure your own ecological footprint and see what kind of present impacts your lifestyle is having on the planet.

From the Earth Overshoot Day website, the lifestyle areas that we can change to help #movethedate

Did you know that currently, we need 1.6 planets to sustain the consumption and lifestyle choices of all the humans alive today!? “From 1961 to 2010, Ecological Footprint accounts indicate that human demand for renewable resources and ecological services increased by nearly 140% “ says a report on our growing ecological footprint.

This is our collective impact, but what is your individual footprint? Click on the image below to do the calculation and see! Then check out the Anatomy of Action to find ways you can reduce your impact and help design a more sustainable future.

Lets take action!

At the UnSchool we are all about agentzing people to help design a future that works better than today, we have classes, handbooks, toolkits, advanced learning tracks and masterclasses all on activating systems change for a sustainable and circular future.

As for the gift, to celebrate Earth Overshoot Day being moved back nearly a month this year, we’re having a 24-hour, 50% off Flash Sale on everything* at UnSchools Online, on this Saturday, 22 August!

Use the code MOVETHEDATE when you checkout, and get 50% off anything in our extensive online learning hub.

Help #MoveTheDate by activating your agency and contributing to making positive change with tools on sustainability, systems thinking, creative problem solving, and more at UnSchools Online!

*for certification tracks this applies to the first month only

A Quick Guide to Sustainable Design Strategies

By Leyla Acaroglu, Originally published on Medium

Sustainable design is the approach to creating products and services that have considered the environmental, social, and economic impacts from the initial phase through to the end of life. EcoDesign is a core tool in the matrix of approaches that enables the Circular Economy.

There is a well-quoted statistic that says around 80% of the ecological impacts of a product are locked in at the design phase. If you look at the full life cycle of a product and the potential impacts it may have, be it in the manufacturing or at the end of life stage, the impacts are inadvertently decided and thus embedded in the product by the designers, at the design decision-making stage.

This makes some uncomfortable, but design and product development teams are responsible for the decisions that they make when contemplating, prototyping, and ultimately producing a product into existence. And thus, they are implicated in the environmental and social impacts that their creations have on the world. The design stage is a perfect and necessary opportunity to find unique and creative ways to get sustainable and circular goods and services out into the economy to replace the polluting and disposable ones that flood the market today. The challenge is which designers will pick up the call to action and start to change the status quo of an industry addicted to mass-produced, fast-moving, disposable goods?

For those that are ready to make positive change and be apart of the transition to a circular and sustainable economy by design, the good news is there is a well-established range of tools and techniques that a designer or product development decision-maker can employ to ensure that a created product is meeting its functional and market needs in ways that dramatically reduce negative impacts on people and the planet. These are known as ecodesign or sustainable design strategies, and whilst they have been around for a while, the demand for such considerations is even more prominent as the movement toward a sustainable, circular economy increases.

Sustainability, at its core, is simply about making sure that what we use and how we use it today, doesn’t have negative impacts on current and future generations' ability to live prosperously on this planet. Its also about ensuring we are meeting our needs in socially just, environmentally positive and economically viable ways, so its very much a design challenge. Consumption is a major driver of unsustainability, and all consumer goods are designed in some way.

When sustainability is applied to design, it enlightens us to the impacts that the product will have across its full life cycle, enabling the creator to ensure that all efforts have been made to produce a product that fits within the system it will exist within in a sustainable way, that it offers a higher value than what was lost in its making, and that it does not intentionally break or be designed to be discarded when it is no longer useful. Provisions should have been made so that there are options for how to maximize its value across its full life cycle and keep materiality in a value flow. This is otherwise known now as the circular economy and the practice of enabling this is circular systems design.

Long before there was a Twitter hashtag devoted to all things sustainability, sustainable design pioneers like Buckminster Fuller and Victor Papanek were figuring out how to reduce the impact of produced goods and services through design. As the sustainability concept has evolved, so has the framework for the thinking and doing tools that we now can routinely integrate into our practices to help understand and design out impacts and design in higher value. I see sustainable design as one of the tools that we each need to employ in order to make things better, its the practical side of considering sustainability, connected to considerations around life cycle thinking, systems thinking, circular thinking and regenerative design. By understanding these approaches, a toolbox for change can be created by any practitioner to advance their ability to create incredible things that offer back more than they take. This should be the goal of any creative development.

The ecodesign strategy set for sustainable design includes techniques like Design for Disassembly, Design for Longevity, Design for Reusability, Design for Dematerialization, and Design for Modularity, among many other approaches that we will run through in this quick guide. Basically, the ecodesign strategy toolset helps us think through the way something will exist and how to design for value increases whilst also maintaining functionality, aesthetics, and practicality of products, systems, and services. It’s especially effective when applying materiality to any of the creative interventions you are pursuing in your changemaking practice, be it a designer or not. We have a free toolkit for redesigning products to be circular that also details all of these strategies, and more.

For decades, much progressive experimentation and exploration of ecodesign, cleaner production, industrial ecology, product stewardship, life cycle thinking, and sustainable production and consumption has occurred, which all led up to the current framing of a new approach to humans meeting their needs in ways that don’t destroy the systems needed to sustain us. Right now the framing is around creating a sustainable, regenerative, and circular economy, whereby the things we create to meet our needs are designed to fit with the systems of the planet and maintain materials in benign or beneficial flows within the economy, which requires businesses to change the way they deliver value and consumers to adjust their expectations around hyper-consumerism. Central to this success is the design of goods and services and that's where these strategies and designers' creativity fit in.

There have been thousands of academic articles and business case studies on a multitude of different approaches to sustainable and ethical business practices, demonstrating the strong and clear need for systems-level change. Contributions from biomimicry, cradle to cradle, product service systems (PSS) models, eco-design strategies, life cycle assessment, eco-efficiency and the waste hierarchy all fit together to support this approach to sustainable design.

The Circular Economy

Within the last 20 or so years, we have really started to feel the negative impacts of what's called the linear economy, where raw materials are extracted from nature, turned into usable goods, purchased and then quickly discarded usually due to poor design choices, inferior materials or trend changes (or the more insidious practice of planned obsolescence). Recently, there has been a great framing around the shift from linear to circular systems called The Circular Economy Framework, which combines a range of pre-existing theories and approaches. Moving to a circular economy (which embraces closed-loop and sustainable production systems) means that the end of life of products is considered at the start, and the entire life cycle impacts are designed to offer new opportunities, not wasteful outcomes.

Our interpretation of the value flows within the circular economy from the Circular Systems Design handbook.

You may be wondering — especially if you aren’t a designer — how can we integrate this into a creative practice to make a positive change? Well, here’s the thing, the approaches to understanding and reducing the impacts of material processes are really important to reduce the use of global materials and the ecological impacts of our production and consumption choices. This is what the circular economy movement is seeking to achieve: a transformation in the way we meet our material needs.

On top of that, these approaches are very empowering for non-material decisions — you start to see the ways in which the world works and can apply this thinking to different problem sets. Sustainable design and production techniques allow for reducing the material impact by maximizing systems in service design — thus, providing sustainability during both production and consumption.

From our free educational project, The Circular Classroom. Find out more here

EcoDesign Strategies

These sustainable design strategies are best known as starting off with Victor Papanek in the 1970’s and have been contributed to over the years by many different people and approaches. This curated life of ‘design for x’ strategies takes into consideration the circular economy and how they relate to closing the loop and dramatically changing economic models.

In this list I have curated, I have also included a few “negative” design approaches at the end to remind you what not to do, and how easy it is to accidentally do the wrong thing right, rather than the right thing a little bit wrong.

In order to achieve circular and sustainable design, some, or many, of these design considerations need to be employed in combination throughout the design process in order to ensure that the outcome is not just a reinterpretation of the status quo, but something that actually challenges and changes the way we meet our needs.

These approaches are lenses you apply to the creative process in order to challenge and allow for the emergence of new ways to deliver functionality and value within the economy. There are also separate considerations of the circularization process outlined in the next section.

Product Service Systems (PSS) Models

One of the main ideas of the circular economy is moving from single-use products to products that fit within a beautifully designed and integrated closed-loop system which is enabled through this approach. Think of alternatives to purchasable products such as leasable items that exist as part of a company-owned system or services that enable reuse. Leasing a product out — rather than selling it directly — allows the company to manage the product across its entire life cycle, so it can be designed to easily fit back into a pre-designed recycling or re-manufacturer system, all whilst reducing waste.

By transitioning away from single end-consumer product design to these PSS models, the relationship shifts and the responsibility for the packaging and product itself is shared between the producer and the consumer. This incentivizes each agent to maintain the value of the product and to design it so that it’s long-lasting and durable. PSS requires the conceptualization of meeting functional needs within a closed system that the producer manages in order to minimize waste and maximize value gains after each cycling of the product. Many of the circular economy business models are either based on this concept or create services that enable the ownership of the product to be maintained by the company and leased to the customer. But it’s critical that this is done within a strong ethical framework and not used to manipulate or coerce people, as this could also easily be the outcome of a more explorative version of this design approach.

Product Stewardship

In a traditional linear system, producers of goods are not required to take responsibility of their products or packaging once they have sold the product into the market. Some companies offer limited warranties to guarantee a certain term of service, but many producers avoid being involved in the full life of what they create. This means that there are limited incentives for them to design products with closed-loop end of life options. In a circular economy, producers actively take responsibility for the full life of the things they create starting from the business model through to the design and end of life management of their products.

Product stewardship and extended producer responsibility are two strong initiatives that encourage companies to be more involved in the full life of what they produce in the world. There are several ways that this can occur; in a voluntary scenario, companies work to circularize their business models (such as a PSS model) or governments issue policies that require companies to take back, recapture, recycle or re-manufacture their products at the end of their usable life. For example, the European Union has many product stewardship policies in place to incentivize better product design and full life management such as the Ecodesign directive, WEEE, Product Stewardship and now the circular economy directives.

The key here is that the design of both the products and the business case is created to have full life-cycle responsibility and is managed as an integrated approach to product service delivery so that the product doesn't get lost from the value system. Partnerships between organizations can enable a rapid introduction of product stewardship, such as a bottling company leasing the service of beverage containers to the drinks company. One key element of this is a take-back program, whereby the producing company offers to take back and reconfigure, repair, remanufacture or recycling the products they produced. This incentivizes them to design them to be easily fixed, upgraded or pulled apart for high-value material recycling.

Dematerialization

Reducing the overall size, weight and number of materials incorporated into a design is a simple way of keeping down the environmental impact. As a general rule, more materials result in greater impacts, so it’s important to use fewer types of materials and reduce the overall weight of the ones that you do use without compromising on the quality of the product.

You don’t want to dematerialize to the point where the life of the product is reduced or the value is perceived as being less; you want to find the balance between functional service delivery, longevity, value and optimal material use.

Modularity

Products that can be reconfigured in different ways to adapt to different spaces and uses have an increased ability to function well. Modularity can increase resale value and offer multiple options in one material form. Just like you can build anything with little Lego blocks, modularity as a sustainable design approach implicates the end owner in the design so they can reconfigure the product to fit their changing life needs.

As a design approach for non-physical outcomes, modularity enables creatives to consider how the things they create can be used in different configurations. This is all about making this adaptable to different scenarios and thus increase value over time. It’s important to ensure designs are durable enough to withstand being taken apart and reconfigured, as well as making it easy to do and the style timeless so it increases its duration of use. Modularity should also increase recycling and repairability by offering replacement parts and a service model.

Longevity

Longevity is about creating products that are aesthetically timeless, highly durable and will retain their value over time so people can resell them or pass them on. Products that last longer aren’t replaced as frequently and can be repaired or upgraded during their life as long as their style and functionality have durability as well.

Ensure that the materials you select enable a long life, and be sure to consider multiple use case scenarios such as repair options and resale encouragement.

Disassembly

Design for disassembly requires a product to be designed so that it can be very easily taken apart for recycling at the end of its life. How it is put together, the types of materials that are used and the connection methods all need to be designed to increase the speed and ease of taking it apart for repair, remanufacturing and recycling. Often the case with technology, the norm is to design products that lock the end owner out, discouraging any form of repairability during the use phase while also reducing the likelihood of recapturing the materials at the end of life.

This design strategy is particularly relevant to technology, requiring the design of the sub and primary components to be just as easily disassembled as it is to manufacture them. For maximum recapture, we need to reduce the number of different types of materials, the connection mechanisms, and the ease of extraction. This is a super critical strategy for monitoring technical materials inflow to reduce negative impacts at end of life.

Recyclability

Making a recyclable product goes beyond simply selecting a material that can be so. You have to consider the recyclability of all the materials, the way they are put together and the use case, along with the ease of recycling at end of life. Relying on something being “technically recyclable” as a sustainable design solution to your product is just lazy and often does not result in environmental benefits, as recycling is very much broken. So, you need to ensure that it is being designed to maximize the likelihood that it will be recaptured and recycled in the system it will exist within.

Assembly methods will impact how easily disassembled for recycling products will be. Also, make sure that there are systems in place so that the product can actually be recycled in the location it will end up! For it to be circular, the product has to fit within a closed-loop system, and recycling often is the least beneficial outcome since we lose materials and increase waste through this system.

Connected to disassembly is the ability to easily and cost-effectively recapture the material at end of life. Just making something recyclable does not guarantee that it will be recycled, as it’s often costly and time-consuming. Additionally, many technology items are shredded to get the valuable parts (like gold) instead of getting all the different parts back. What is crucial about this strategy is that it must be used in a system that has the appropriate and functioning recycling market, or a take-back and recapture system must be in place, as well as design features that maximize the behavioral outcomes of the end owners so that the product is actually reacquired and recycled. The Scandinavian bottle recycling system is a perfect example of this. Drink bottles are made of thick and durable materials that can be washed and re-manufactured, and the system is set up with an easy-to-use deposit program and financial incentive to maintain a high level of recapture.

Repairability

Repair is a fundamental aspect of the circular economy. Things wear out, break, get damaged, and need to be designed to allow for easy repair, upgrading, and fixability. Along with the extra parts and instructions on how to do this, we need systems that support, rather than discourage, repair in society. For example, many Apple products are intentionally designed to be difficult to repair, with patented screws and legal implications for opening products up.

Sweden recently opened the world’s first department store dedicated to repair, but any product producer can put mechanisms into place for ease of repair so that the owner has more autonomy over the product and will be encouraged to do so. The Fair Phone is a great example of this.

Reusability

Repair allows the end owner to maintain its value over time, or sell it more easily to then increase its lifespan. But there is also the option of designing so that the product can be reused in a different way from its intended original purpose, without much extra material or energy inputs. An example of this is a condiment jar designed to be used as a water glass.

There are many ways a product can serve a second or even third life after its core original purpose. This approach is useful when you have limited options for designing out disposability.

Re-manufacture

For this strategy, the producer takes into consideration how the parts or entire product can be re-manufactured into new usable goods in a closed-loop system; it’s critical to the technology sector but fits perfectly for many products.

Re-manufacturing is when a product is not completely disassembled and recycled or reused, but instead, some parts are designed to be reused and other parts recycled, depending on what wears out and what maintains its usefulness over time.

Efficiency

During the use phase, many products require constant inputs, such as energy, in the form of charging or water in the form of washing. When a product requires lifetime inputs, it’s called an “active product”, meaning it is constantly tapping into other active systems in order to achieve its function. That’s when design for efficiency comes in, designing to dramatically reduce the input requirements of the product during its use phase.

This will increase the environmental performance and also reduce wear of the product, increasing lifetime use. This approach can also be taken as an overarching one — design to maximize the efficiency of materials, processes, and human labor. As a general rule, “Weight equals impact,” and the more efficient you can be with materials, the lower the overall impact per product unit (this rule has many exceptions, as it is always related to what the alternatives are).

Influence

Things we use influence our lives. This is why social media applications are designed to act like slot machines with continuous scroll, and why airport security lines make you feel like a farm animal. The things we design in turn design us, and thus there is a huge scope for creating products, services, and systems that influence society in more positive ways.

There is still a lot of resistance to sustainability, often because it seems confusing. So, imagine how you can design things that give people an alternative experience to this mainstream perspective. Designing in positive feedback loops to the owner helps change behaviors, just as designing in less options to limit confusion can help direct the more preferable use.

Equity

Accidentally or intentionally, many goods are designed to reinforce stereotypes. Pink toys for girls, dainty watches for women, and chunky glasses for men are a few examples. Reinforcing stereotypes subtly maintains negative and inequitable status quos in society. There are entire labs dedicated to first researching an established trend, and then designing to reinforce it. Design for equity requires the reflection and disruption of the mainstream references that reinforce inequitable access to resources, be it based on gender or outdated stereotypes.

Oppression and inequality exist everywhere, from toilet seat designs to office buildings. Considering the potential impact of your designs on all sorts of humans is critical to creating things that are ethical and equitable. This also applies to the supply chain, ensuring that people along the full chain of materials and manufacturing are valued, paid fairly and respected.

Systems Change

Perhaps the most important of the design strategy tools is the ability to design interventions that actively shift the status quo of an unsustainable or inequitable system. The world is made up of systems, and everything we do will have an impact in some way of the systems around us. So instead of seeing your product as an individual unit, see it as an animated agent in a system, interacting with other agents and thus having impacts.

All systems are dynamic, constantly changing and interconnected. Materials come from nature, and everything we produce will have to return in some way. So, designing from a systems perspective with the objective of intervening will allow for more positively disruptive outcomes to the status quo (see my handbook on the Disruptive Design Method for more on this approach).

Other things to consider

Where is the energy being sourced? Shift from fossil to renewables.

What are the hidden impacts embedded within the supply chain? Remove embodied fossil fuel energy.

How can you recover and put to good use all wasted resources across the supply chain? Look for industrial symbiosis or by-product reuse opportunities.

How can you design in life extension on your products? Design repair and rescue options as a service for your products.

Are there ways of partnering to create industrial symbiosis where your product’s by-products are used as raw materials for another process? Reduce waste to landfill by encouraging secondary industries to use industrial by-products.

How can you design your product to be a service instead? Embrace full product stewardship.

Do you need to produce a product to deliver the functional need? Look for alternative business models to deliver your customer’s functional desires.

What is the energy mix in the manufacturing and use phase? The types of energy used will increase or decrease environmental impacts.

Does a product need to exist or can we deliver value and function in a different format?

The UnSustainable Design Approaches!

There are many insidious techniques used by designers to manipulate and coerce consumers into behaviors and practices that are unsustainable and inequitable. Here are three types you should avoid! There are also many accidental actions that may have good intentions that result in greenwashing, so be careful not to invest more in marketing green credentials than in R&D to ensure your product truly is what you claim it to be.

Design for Obsolescence

Planned obsolescence is one of the critically negative ramifications of the GDP-fueled hyper-consumer economy. This is where things are designed to intentionally break, or the customer is locked out through designs that limit repair or software upgrades that slow down processes. This approach tries to constantly turn a profit by manipulating a usable good so its functionality is restricted or reduced and the customer is forced to constantly purchase new goods. It’s in everything from toothbrushes to technology. The habit has led to massive growth, but at the expense of durability and sustainability. How it is used as a positive strategy is when it is part of a well-designed closed-loop system that enables the product to naturally “die” at the right time so it can be reintegrated into the system it is designed within.

Design for Disposability

Designing for things to break is due to the cultural normalization of disposability as a result of increased use of disposability in the design of everyday goods. From coffee cups to technological items, it is a race to the bottom of our economy, where many reusable things have become hyper-disposable. Single-use items plague our oceans with plastic waste and increase the end cost for small businesses and everyday people, as the more addictive the cycle of disposability is, the more costly it becomes to deliver basic service offerings. I have written extensively about this; read more here.

Dark Patterning

A term coined by designer Harry Brignull, the idea of dark patterns are intentional tricks used by designers to manipulate and lure customers into taking actions they don’t necessarily make the choice to do or may otherwise not agree to. Dark patterning includes often exploiting cognitive weaknesses and biases to get people to do things like purchasing extra items they did not need when checking out online, or creating a sense of urgency to increase purchasing — leveraging single-click buy now for impulse buys, using particular colors to evoke emotions and sharing outright misleading information to increase purchases. This website has many great examples.

LOOKING FOR MORE?

Much of this content is from my handbook on Circular Systems Design, and over at the UnSchool Online, I have a short course on sustainable design strategies and a more extensive one on sustainable design and production. You may also like to find out about the Disruptive Design Method that I created to support deeper design decisions that works to help solve complex problems. I also created the Design Play Cards which include all the eco-design strategies and fun challenges to solve.

5 Reasons It’s Time for Nature | World Environment Day 2020

Do you think it’s time for nature? The United Nations does, as “Time for Nature” is the theme for this year’s World Environment Day, which is celebrated each year on the 5th June. Of course it's in our opinion that every day should be a day to celebrate the magical natural beauty of the only known life-sustaining planet in the universe.

But we also wanted to take this opportunity to explore some of the top reasons why biodiversity is so bloody awesome and important, especially in a time where we are challenged by a global pandemic in which many top researchers and scientists warn that nature is sending us a message, drawing clear links between natural systems destruction and the rise of communicable diseases.

Nature provides all the goods and services we need to operate the economy, not to mention life. We’ve only recently lost sight of the power and importance of nature in our human existence, with the last 70ish years creating the rise of hyper-convenience-fueled lifestyles that in turn created demand for the design of disposability that then led to environmental crises like ocean plastic pollution, climate change, destructive bushfires, freak weather events and deforestation - all issues that impact biodiversity. As these issues continue to be amplified as causes for encouraging sustainable lifestyles to be on the rise, the world is reawakening and reconnecting to the unrivaled power and importance that nature uses in creation and destruction alike.

Here are five compelling reasons why this theme is so important, right now especially:

1. Biodiversity is critical to ecosystem success

Simply put, biodiversity is what makes Earth, Earth. Without diversity, we have weak systems that are susceptible to disease — which then breeds a new onslaught of system impacts. The UN explains that biodiversity encompasses the over 8 million species – from plants and animals to fungi and bacteria – that are all interconnected and share our planet as home. All ecosystems need diversity to succeed. The oceans, forests, mountain environments and coral reefs are all teaming with genetic diversity of all manner of plants and animals. Ecosystems sustain human life in a myriad of ways, cleaning our air, purifying our water, ensuring the availability of nutritious foods, nature-based medicines and raw materials, and reducing the occurrence of disasters.

To learn more about biodiversity and find out more about what you can do, check here for the UN’s “Practical Guide” to Earth Day 2020.

“At least 40 per cent of the world’s economy and 80 per cent of the needs of the poor are derived from biological resources. In addition, the richer the diversity of life, the greater the opportunity for medical discoveries, economic development, and adaptive responses to such new challenges as climate change”. - The Convention about Life on Earth, Convention on Biodiversity

2. All the beauty in the world comes from nature

There’s a reason that #naturephotography is hashtagged over 108 million times on Instagram. No manufactured life experiences can take the place of the beauty of what surrounds us every day in stunning sunrises, lush landscapes, and wondrous wildlife. We humans are biologically hardwired to be connected to nature (more on that in #3), and throughout human history we have been inspired and fulfilled through the unique, diverse natural beauty around the world. This inspiration isn’t just a feel-good philosophical inspiration (though, who doesn’t love to just feel the warm fuzzies when you see a baby animal or take in a breathtaking view) — it’s a literal contribution to the evolution of our species through ideas like biomimicry and circular systems design. It's also no wonder that one of the most watched TV series of the last fifteen years was David Antenborugh’s Planet Earth series.

This collection of videos from TED Ed perfectly explores the wonderment of nature — not just in our environment but truly in an interconnected look at the nature of stuff, the nature of design, the nature of collection action, and of course, the nature of change.

People must feel that the natural world is important and valuable and beautiful and wonderful and an amazement and a pleasure. - David Attenborough

3. The human brain needs time in nature to restore itself — and thrives when exercising outdoors.

There is mounting evidence that time in nature has huge benefits to the human brain and our bodies. While most attention has been given to the psychological impacts of nature on human well-being, like increased happiness and creativity boosts, other benefits like reduced hypertension and cardiovascular disease, and even lower risks of chronic conditions like asthma, diabetes, and obesity have also been found.

Over the last 10 years, we’ve learned that healthier soil microbes yield healthier humans (although, Marco Polo noted in 1272 in his travel diary that the people of Persia’s foul moods were attributed to the soil and conducted his own qualitative study by importing soil from Persia to his banquet hall!) and that three days in nature basically resets your brain. Additionally, exercising outdoors (just a walk will do) has shown improved cognition and increased neuroplasticity, which interestingly helps slow aging.

4. Literally everything we need to sustain our lives comes from nature

Nature is beyond crucial to our personal health and wellbeing, as it provides all the foods, air and drinkable water we need to exist! Complex systems all interact to allow for plants to photosynthesize, create oxygen and filter water. We all are in an interdependent relationship with nature, and as long as we ignore that basic fact of life, we continue to ignore the need for political and cultural changes that will not just protect nature but also find incredibly regenerative solutions that enable us to live within nature and continue to advance our civilization into the future. Technically the services provided by nature are called ecosystem services, and there are more than one could imagine all working together quickly and tirelessly to help life on Earth flourish. So, next time you take a breath or eat a strawberry or drink water and get hydrated, take a moment to think of nature and all the services that the giant ecosystem of Earth provides for us for free.

Nature’s oxygen factory

Every second breath of oxygen comes from the ocean

5. Nature is in a state of crises too

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) recently declared that nature is in a state of crises too. Aside from the links between coronavirus, climate change and nature's destruction, nature itself is seeing species being lost at a rate 1,000 times greater than at any other time in recorded human history, and one million species face extinction, making this time what scientists call the sixth great extinction. The only difference is it's not a meteoride this time — instead, it is us who are responsible for this mass extinction event. Scientists have also found something akin to an insect apocalypse, with bees and other pollinators being killed off in the millions.

“Healthy ecosystems can protect against the spread of disease: Where native biodiversity is high, the infection rate for some zoonotic diseases can be lowered,” says United Nations Environment programme (UNEP) biodiversity expert Doreen Robinson.

The foods we eat, the air we breathe, the water we drink and the climate that makes our planet habitable all come from nature.

Yet, these are exceptional times in which nature is sending us a message:

To care for ourselves

we must care for nature.

It’s time to wake up.

To take notice.

To raise our voices.

It’s time to build back better

for People and Planet.

This World Environment Day,

it’s Time for Nature.

So yes, it’s absolutely time for nature not just today, but every single day, from now until we figure this shit out and implement transformational systems change.

To further celebrate and help you get activated to support the global transition to a sustainable and regenerative economy, we are having a flash 50% off sale on everything over at online.unschools.co for this week until June 12! Use code: timefornature all week (ends midnight 5th June GMT time)

The Case for a Post Covid-19 Sustainable Recovery

As the world starts to reawaken from its months of in-house sheltering during the COVID-19 crises, there are calls from around the world for the rebuilding of the economy to be done through a green and sustainable pathway. The lockdown has shown many people just how urgent our sustainability needs are. There are many links drawn between natural habitat destruction, climate change, air pollution and other environmental issues connected to the rise and devastation of a pandemic such as COVID-19. The head of the UN called for a global green recovery, and many governments are seeing the links between the climate and the COVID-19 crises. With recovery talks emerging and governments around the world beginning to propose new budgets, we thought we’d take a look at who is (and who is not) focused on implementing sustainability initiatives in their COVID-19 response and future planning.

Dan Meyers via Unsplash.com

The European Union

Right before this crisis, the EU voted to approve the Green Deal, which sets out ambitious plans for a clean and circular economy that has no new net carbon emissions by 2050. This pandemic has emphasized the urgency of implementing the Paris Agreement, with Germany and the UK collaborating to virtually lead the the 11th Petersberg Climate Dialogue earlier in April, in which they, along with 30 countries, discussed how to begin recovery with the caveat of climate protection being linked to the economic perspective. The EU’s proposed Green Recovery also highlights the need to protect biodiversity and invest in “sustainable mobility, renewable energy, building renovations, research and innovation, and the circular economy.” While there isn’t unanimous agreement among all nations of the EU, there is certainly a majority that are in favor of using the European Green Deal as a framework for recovery, leading to rich discussions and (hopefully) favorable outcomes.

“The restart can lead to a healthier and more resilient world for everyone.” - U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres (Source)

As usual, the main pushback against green initiatives is coming from a fiscal perspective (these are the people who created the reductive, linear economy based on the hyper consumption loop, after all). We saw this happen in 2008’s recession as well — carbon dioxide levels drastically dropped and then resurged with a vengeance due to carbon-intensive stimulus spending. As such, hundreds of the world’s top economists have banded together to advise that we learn from the 2008 crisis and choose more wisely this time by investing stimulus spending in climate action, stating that “post-crisis green stimulus can help drive a superior economic recovery.” This resounding call for a green recovery is also heard from the general populace, with over a million EU citizens sharing their support for green investments. Specific countries are also putting in measures such as France offering subsidies for bike repairs to entice people to bike rather than drive.

“The current crisis is a stark reminder of how closely human and planetary health are interlinked - only together can people and nature thrive. A green recovery means restoring nature, protecting our environment, and accelerating the transition to a carbon-neutral and resilient economy. MEPs must lead the way." - Ester Asin, director of the WWF European Policy Office (Source)

Markus Spiske via Unsplash.com

New Zealand

Aside from having the leader many of us want for our own countries in Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern (The Atlantic hailed her as “the world’s most effective leader”), New Zealand has given personhood to a river, prioritized wellness as part of their economy, and now they are looking at ways they can rebuild in a greener and more sustainable way. For example, in the $50B recovery budget that was just proposed, they’ve allocated $1B toward environmental spend, creating 11,000 news jobs, and $430M is included for unemployed people to help clean up rivers and restore wetlands, as well as $300M is being allotted to prevent loss of biodiversity. To further improve energy efficiency, New Zealand is also investing $56M in their heating and insulation program, which simultaneously improves citizens’ health and thus reduces their vulnerabilities to diseases like COVID-19.

Dan Freeman via Unsplash.com

United States

Politics and science continue to be at odds in the US, with environmental science particularly taking a hit since the current administration took office in 2017 and proceeded to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, roll back regulations on emissions in favor of the fossil fuel industry, and aggressively cut trees on public lands, among many other actions that have drastically changed and reduced US environmental policies. A bright spot came about, however, when the Green New Deal was proposed in 2019, led by the popular Democratic representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. While widely rejected at the vote, the Green New Deal continues to be a powerful framework for progressive ideas and is currently being praised by scientists for its relevance to the COVID-19 recovery. While as a whole the US is falling behind on the world stage in this matter, a few progressive states like California are talking about how clean energy jobs can be significant in economic recovery, and thought leaders are at least envisioning what the future of the US could look like with green initiatives in place. For now, it’s still a fantasy, but we remain hopeful.

Researchers from University of Massachusetts working on the potential of growing crops under solar panels panels and the mutual benefits with agriculture (via Unsplash.com).

Asia

China and South Korea are leading the way in investing in sustainable recovery among Asian nations. With a total of $7T pledged as economic stimulus, China is heavily investing in infrastructure for electric vehicles, renewable energy, smart cities and smart grids, and healthier cities via focusing on reducing pollution, implementing stricter emissions standards, improving health facilities, creating more space for exercise, and promoting road safety.

South Korea has emerged as an international leader in pandemic recovery. It became the first country to hold a national election amidst this pandemic, and as a result has championed a 2050 carbon neutrality goal, along with proposals for an impressive green recovery. Publishing a “climate manifesto” and giving nod to the EU’s Green Deal for Europe and the US’s Green New Deal, the plan includes “large-scale investments in renewable energy, the introduction of a carbon tax, the phase-out of domestic and overseas coal financing by public institutions, and the creation of a Regional Energy Transition Centre to support workers transition to green jobs.”

Seoul by Daniel Bernard via Unsplash.com

Canada