by Leyla Acaroglu, originally published on Medium

It should not come as a surprise to anyone that our current linear economy relies on continuous sales, which requires things to wear out faster, look a bit uglier and quickly become less desirable than the latest version, all in order to keep feeding the linear ‘waste-based’ economy. That’s why consumer products are often made to break, designed with an intentional lack of replacement parts, or have their lifespans controlled by the producer through savvy tech interventions.

The term used to define the practice of intentionally designing products to break or become aesthetically undesirable is called planned obsolescence. This is a well-used technique that companies rely on to increase sales through manipulating consumer desires and product functionality. It manifests itself in all types of products, from high-end tech to appliances, to fashion and even furniture.

When a product is designed this way, it’s hiding all sorts of tactics that are intended to lock owners out of the products they have purchased by making it nearly impossible to repair or upgrade once they break.

There are a few ways that this occurs. One is to restrict the availability of spare parts and add clauses to user agreements that state that warranties are voided or even that it’s illegal to use third-party repairs or products. Another way is to throttle usability, such as reducing the operating speed of a tech product or designing a battery to wear down after a certain number of recharges (not to mention making it impossible to get into the battery to replace it when this happens!). Products can also be easily made to appear old or outdated by manufacturers as they introduce newer versions of their best sellers. This is called aesthetic obsolescence, and it has its roots in the car industry.

To maintain the benefits of a closed system, producers work to ensure that they have legal and technical rights over their goods through iron-clad user agreements (who really reads them anyway!?) and even upgrades that limit their use (such as printers that don’t work when you use non-authorized ink cartridges — this NPR podcast tells a great story about this). Home printer companies are notorious for this kind of practice, with them losing several legal cases where consumers fought back against their tactics.

As more and more products become part of the internet of things, I wonder if all our tech-enabled consumer products will move toward limited functionality by design as well? After all, it’s a money-generating (and thus addictive) business model. What irks me the most about these insidious practices is that we citizens have limited rights to repair, and in many cases, there are great inequalities as people get trapped in continual consumption cycles that are bad for their bank balances and for the planet as a whole.

There are a host of consumer rights eradicated by these practices. What’s more infuriating than being fleeced of money for products we already own is that the material losses are far greater than just our bank balances. We eat into future resources every single time tech is wasted, not repaired or prematurely turned obsolete. Phones and laptops contain many different complex materials, including rare Earth minerals, all of which (as the name implies) are in limited supply on Earth — not to mention, there are stark concerns around the ethics of the mining of these minerals along with the energy expenditure required to dig them up in the first place!

When companies lock us citizens out of the products they produce, they are manipulating the market so that we are forced to continue to buy replacement products over and over again despite our frustration. This means people who may already be vulnerable to market changes are further disadvantaged, as re-purchasing brand new products is expensive.

But right now, so is repair!

Last week, I managed to spill my morning coffee on my cell phone as I accidentally kicked the phone off a table (don’t even ask). The result was a messy floor and a broken screen with a dash of coffee in it. I looked up a local repair shop and within an hour and a half the nice man had replaced my screen — all I had to do was part with 160 pounds. Given the cost of a replacement phone is 4 or 5 times higher than that (and I’m obsessed with sustainability), once I got over the sting, I felt the price was a fair exchange for his skills in fixing my mistake. The only issue is that since the phone company doesn’t want me or him to repair their products, they don’t issue any parts to independent repair shops. In fact, what we just did is actively policed by phone companies like Apple. The new screen is not an official replacement product (as these are not available to people outside the phone company), so it also makes my battery drain faster. All of these tactics are designed to disincentivize me from getting my phone repaired under the conditions that suit me (fast and local) and instead, attempt to keep me within a tightly-controlled ecosystem.

I used to have a Fairphone 2, which is a phone designed to allow repair by the user. When I broke that screen (again, don’t even ask, I am a very clumsy person!), I ordered the replacement part online for under $100, it was shipped to me and I replaced the screen myself. I was a bit annoyed that they didn’t offer a take-back service for the now-defunct broken screen part (which was an entire section of the phone), so when that phone finally stopped working (and they had stopped providing upgrades to that product line), I had to get a mainstream phone (albeit reconditioned and second hand).

Repair should be mainstream and accessible. It should not be the exclusive offerings of a small start-up phone company, but a right that we can all engage with when we need to, without breaking any laws or ending up with a battery draining issue! To do this, companies need to offer repair manuals and spare parts, as well as be open to repair being part of their product's life journey.

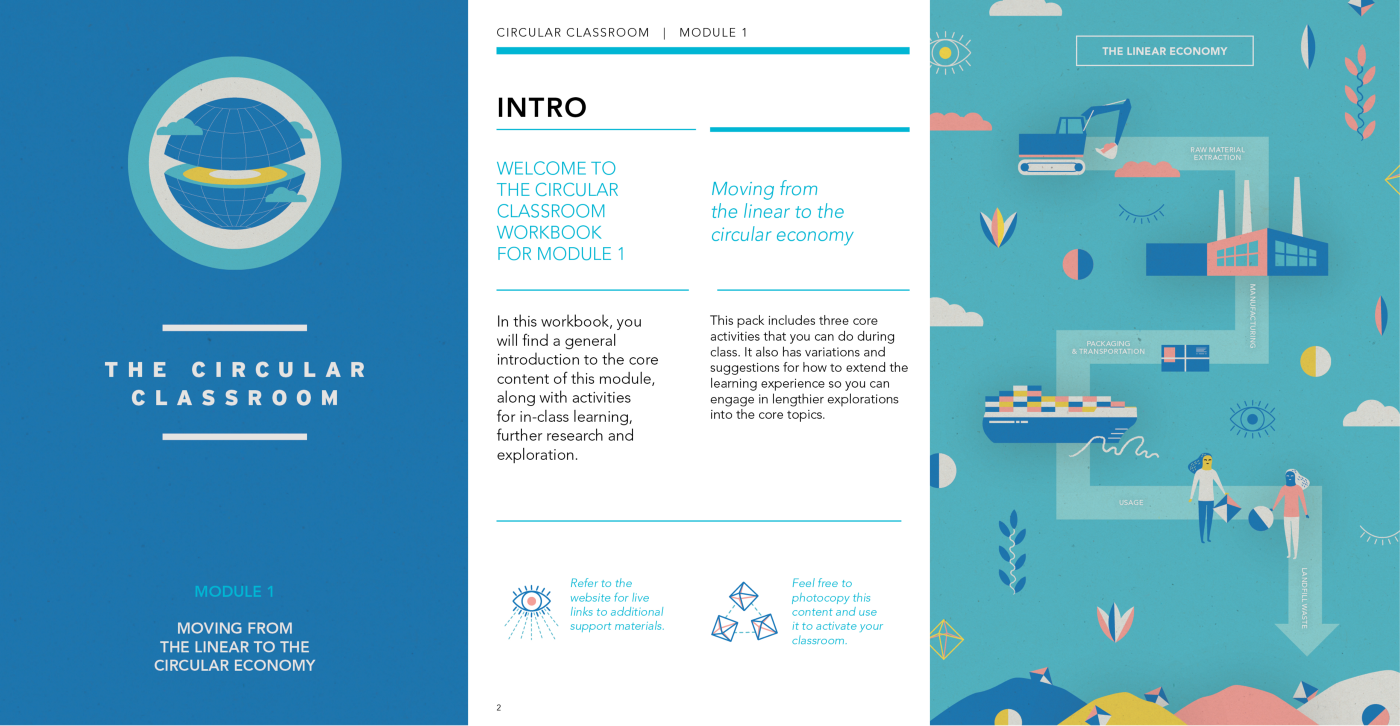

A big part of moving to a circular economy is repair. It’s a far better solution than recycling when it comes to high-value products, as it keeps functionality and materials in play. Repair is also more preferable to remanufacturing, as again, it avoids additional impacts. There is a hierarchy of post-disposable design solutions that can massively reduce waste and move us to a more sustainable future.

Whilst we wait for companies to take the initiative, we need citizen’s rights to repair through consumer legislation. Thankfully, this is happening right now all over the world. France has even gone as far as making planned obsolescence illegal.

The Right to Repair Movement

Fortunately for us, there have been many people fighting for our rights to repair for decades, and they are getting some big wins right now.

The movement has gained a lot of momentum recently, with the EU and UK putting in place new legislation, and last week Joe Biden signing an Executive Order to enable the right to repair across the U.S. This will enable farmers the right to repair their tractors (currently they are locked out by the technology), and it will direct the Federal Trade Commission to create new rules to prevent manufacturers from imposing repair restrictions (such as to your cell phone!).

Biden’s Executive Order will “make it easier and cheaper to repair items you own by limiting manufacturers from barring self-repairs or third-party repairs of their products.” — The Whitehouse Fact Sheet: Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, July, 9, 2021.

A report from PC Mag showed that most Americans support a right to repair, no matter what political side of the aisle they’re on. The more people become aware that they don’t currently have a right to repair, the more the demand grows for legal remedies to this legal loophole that has been exploited at our expense for decades.

Whilst there are many things to celebrate with these new laws, there is still much room for improvement when it comes to eliminating waste by design and giving consumers true rights over the things they own (such as smartphones not being included in the new UK legislation).

The Road to Now

The use of planned obsolescence has been known for decades, and the impacts of waste on the planet too, especially electronic waste. But recently, several high-profile lawsuits (such as both Apple and Samsung having to pay out a few million dollars to settle class-action lawsuits against them intentionally throttling batteries so customers would be forced to upgrade), has made more and more people aware of the practices, which in turn, encourages a stronger legislative demand for consumer protections.

Recently, we have even had the co-founder of Apple Steve Wozniak come out in support of the right to repair. He said there would have been no Apple computer had he not had access to the schematics of tech in the 80s, which enabled him to tinker and create. Apple is not alone; they are like many in the tech sector who avoid releasing any user diagrams or schematics that would make it possible for people to upgrade, repair or adapt the products that they purchased, and should thus technically own.

This method of locking us all out of our consumer goods by limiting our ability to repair or upgrade products that we own has made its way into everything from our tech to our washing machines.

Right to repair is all about extending the useful life of products, making spare parts available for home repairs, legalizing and incentivizing repair and tackling the insidious practice of making things to break (planned obsolescence). These changes will re-enable tinkering and user adaptation; they’ll also save us money and ensure that we have our consumer rights protected.

Companies like iFixit have been working to make repair a normalized part of the design and the consumer community for years. They buy up new products as they are released, and their engineers get to work taking them apart to create the repair manuals and videos that the companies should have created to begin with (and hate them making!). They also sell the toolkits that my phone repair shop probably used to fix my coffee-laden cellular device!

ifixit reporting on right to repair wins for 2020

There are also repair cafes, the repair association, Maker Labs, and a healthy fixer community that has been pushing for these rights for years. So, thank you to everyone who has been campaigning for our rights to be protected and for the better design of products!

Many years ago, in 2011, I ran a week-long collaborative experience around waste and repair called the Repair Workshops (inspired in part by Platform 21’s Repair Manifesto). 10 talented artists and repairers first spent days repairing mounds of broken household stuff that we had been given by a local charity shop that was about to whisk it all off to a landfill (charities are often burdened with huge waste fees from people’s broken donations). Then we spent a few days open to the public, offering free repairs to anyone. It was so moving and amazing to see people of all ages come in with some personal or favorite product that they wanted to have fixed. One lady even brought in some bread with her to test the toaster she had been given on her wedding day 50 years before.

2011 Repair Workshops

Through this project, I discovered that no matter what it is, people often want to keep the things they already own. Repair is a hugely rewarding experience, as something that has lost its functionality is brought back to life again. People not only have an emotional attachment to things that have spent time in their lives, but the value of already having it makes it inherently more valuable.

The lack of replacement parts, skilled repair people and a fixing culture forces us to replace rather than repair, which increases our personal costs and eats into future generations’ ability to have access to natural resources that we are wasting today. Everything new that we make requires huge amounts of natural resources, creates carbon emissions and contributes to all sorts of environmental and social ills.

Repair is not just a fun and money-saving thing to do — it’s a vital part of the transition to the circular economy. Repair is about extending the life of a product, but it’s also about valuing materials that come from nature as well. By designing for repair, it shows that a company also values its customers and their choices. It shows that they have invested in higher-value, longer-lasting products that we should then also invest in.

Whilst the new right to repair bills are welcomed, until companies take proactive action to ensure that the design of their products is sustainable and circular, we will continue to be stuck with things that are made to break, along with limited options for spare parts, along with the tools and skilled people to repair them. We will bear the cost of bad design, and legislators will continue to have to try to fill the gaps of rights that tactics like planned obsolescence take away from us.

Repair is a right that we should all have the option to use when and how we need it.

— -

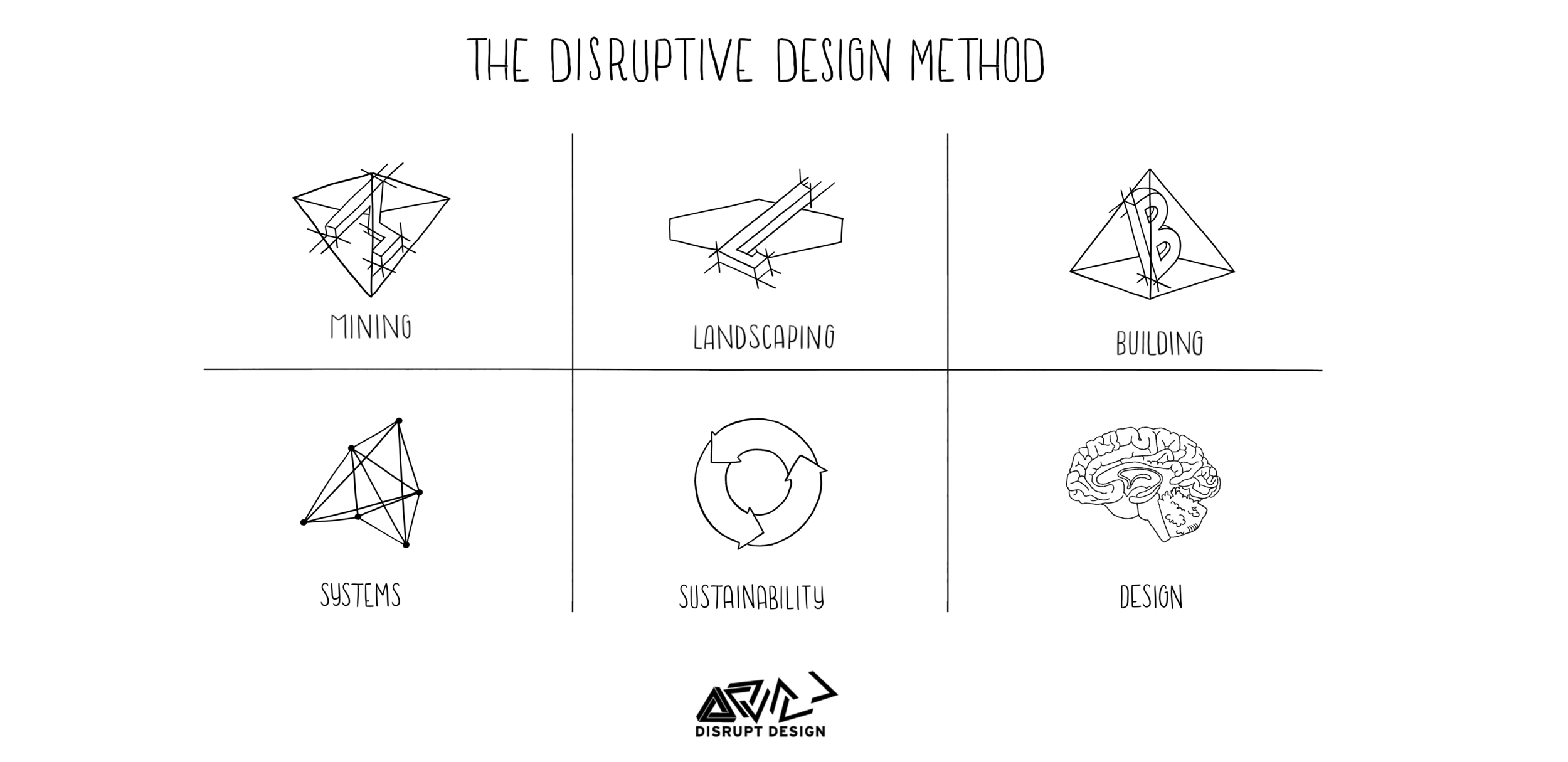

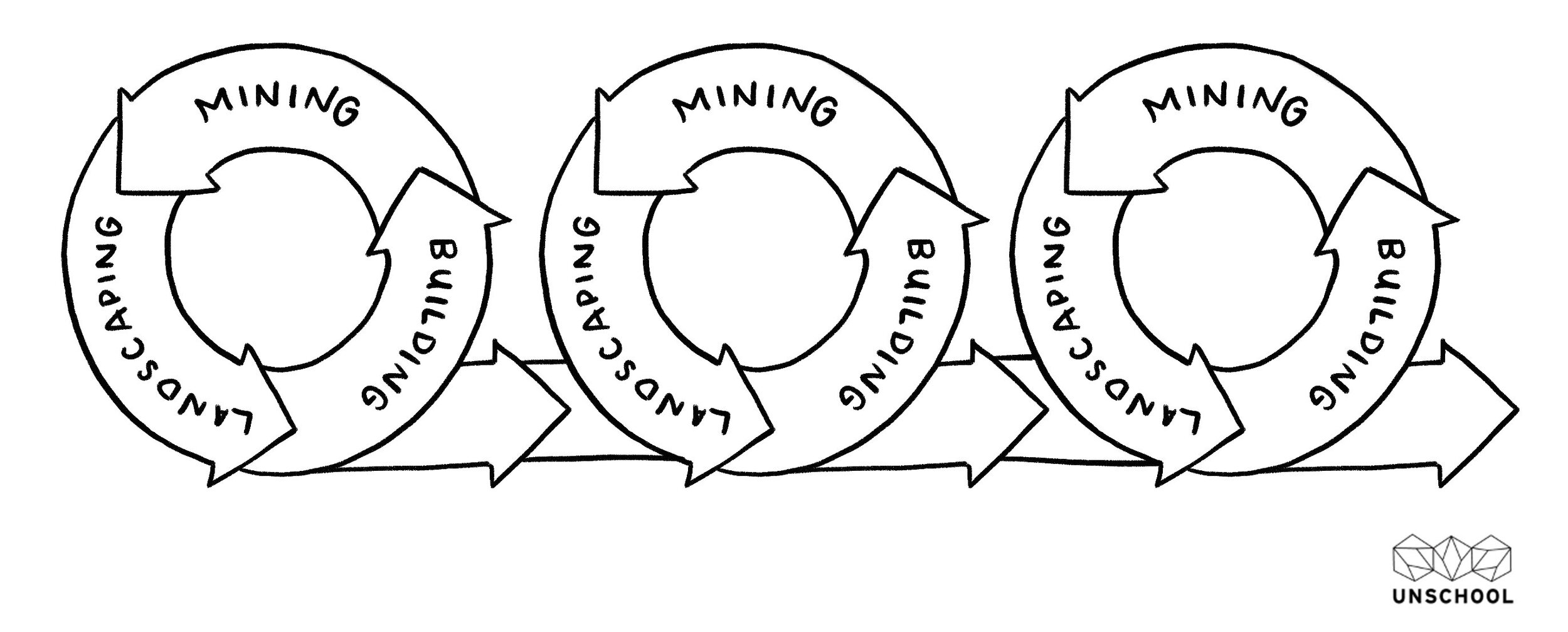

To find out more about designing for the circular economy, check out my handbook Circular Systems Design and my classes on sustainable design and the circular economy.