The UnSchool of Disruptive Design turns 9 years old this week! What an immense pleasure it’s been to create and share this experimental knowledge lab with tens of thousands of people from around the world over the last 9 years.

6 Focused Learning Categories to Boost your Change-Making Skills

Here at The UnSchool, there’s a handful of things that we never stop talking about: making positive creative change, embracing systems thinking, normalizing sustainability, igniting the circular economy, leveraging the Disruptive Design Method, and finally, diving into Cognitive Science by hacking our brains, mindsets and biases so that we can all expand our sphere of influence and active our agency to make massive sustainable changes to the way we live on this beautiful planet we all share!!!

When we started this experimental knowledge lab in 2014, we did so with the intent to give others the tools they needed to disrupt the status quo and solve complex problems in order to make the future work better for us all. Now that we’ve been fully operational for almost 7 years, having transferred knowledge to thousands of change-makers like you all around the world, run fellowships in 10 countries (!), and created >80 offerings at UnSchool Online, we decided to organize our courses, toolkits and ebooks into the themed-knowledge areas that we focus on the most.

Our six brand new learning categories — Systems Thinking, Sustainability, Circular Economy, Creative Change, Disruptive Design, Cognitive Science — are designed to help you find what you need more efficiently and take a more targeted approach to refining your creative change-making skill set. Whether you are brand new to the world of making change or you’re a leader in creative change, we have offerings that can help you build your knowledge bank, refine your skillset, and amplify your impact. These new learning categories are simply like destinations on your change-making journey map, and we’ll step you through where to go based on where you are right now.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll spotlight each of the new learning categories here in our journal to help give you a better understanding of why these focused areas are so important not only to us — but for your work, too. Stay tuned!

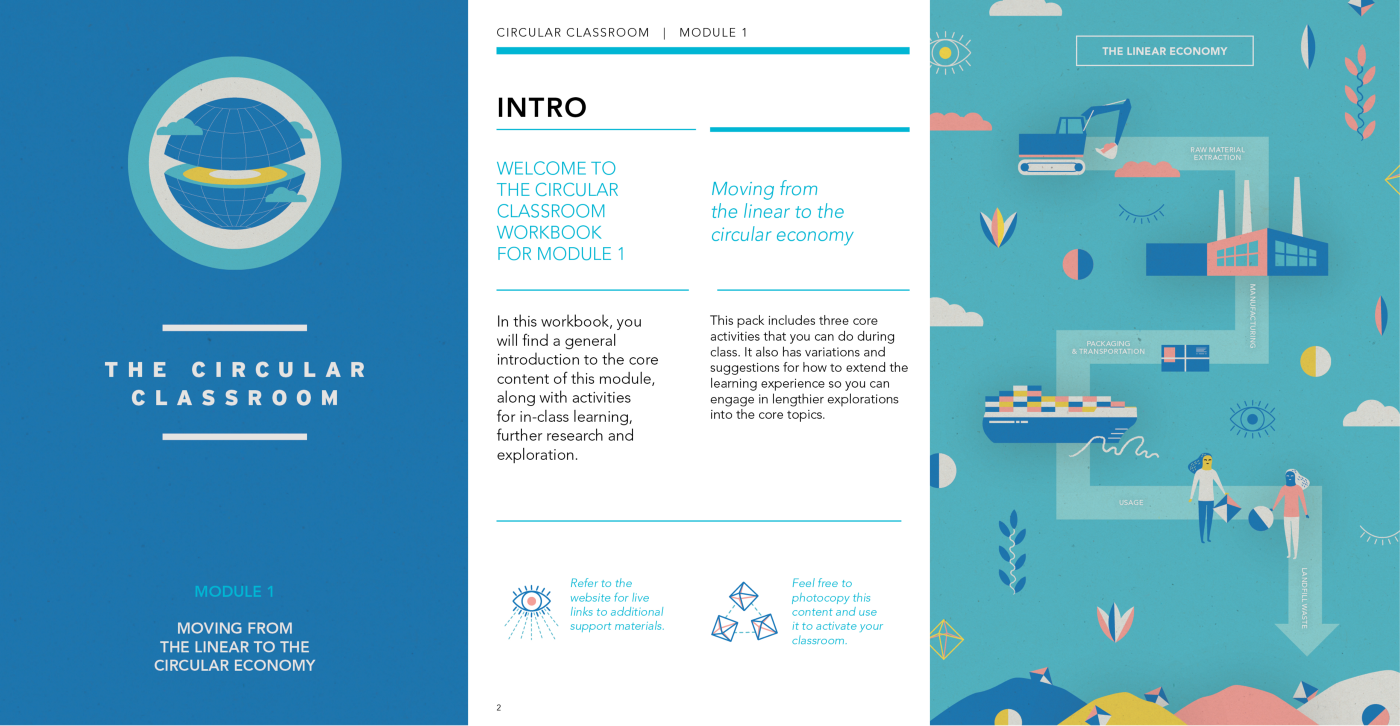

PS: Speaking of knowledge transfer, have you browsed our recently upgraded Free Resource Library lately? It’s packed with brain-activating content (like Leyla’s Decade of Disruption report, or The Circular Classroom or Sustainability in Business!) and practical tools (like the Superpower Activation Kit, the Circular Redesign Kit, and our personal Post Disposable Kit!) that you can utilize right away.

8 Creative Change-Maker Skills You Learn at The UnSchool

We know people like you want to help change the world. What a relief it is to know that you're not alone! The UnSchool was created for people just like you, and you can get involved by joining our blossoming community of creative change-makers from around the world who all agree that we can design a better future.

The UnSchool’s community is made up of creative rebels, problem solvers, and activated change-makers from all walks of life. They are deeply passionate about making positive change — a crew of people wanting to get busy unf*cking the multitude of social and environmental problems around us. Pandemic or not.

For the last six years, we have taught thousands of people how to make positive change. We know that it’s not one person’s responsibility to save the world, but that every single one of us can change it for the better.

The suite of practical tools we share through our online courses and workshops are perfectly tuned to help you take action.

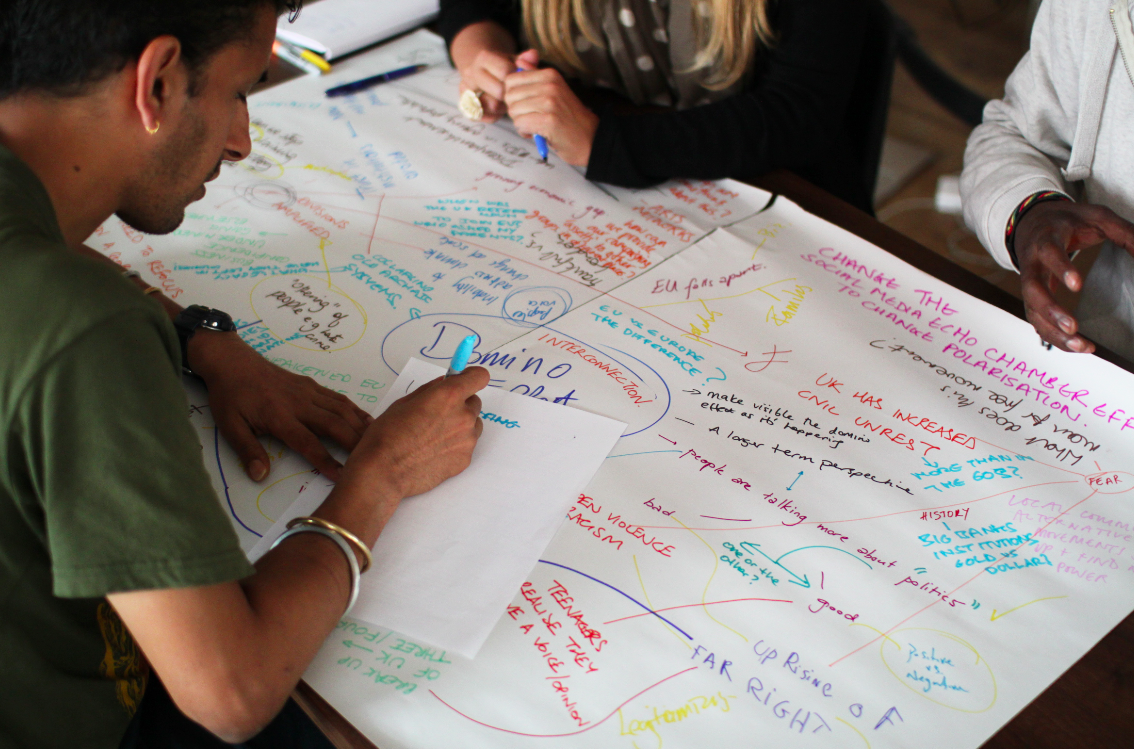

Systems mapping at an UnSchool workshop

Just wanting to be a part of change is not always enough to evoke action. We have to contend with our brain biases that thwart our efforts (Netflix and chill overload, anyone?), even among the most committed of us.

Making impactful, tangible change takes a specific mindset and toolset that helps hack these brain biases. Offering an applied knowledge set that anyone can use, the tools that we share at The UnSchool help you unravel complex interconnected problems and design positively disruptive interventions that leverage change.

When you take an UnSchool offering, you can expect transformative learning that enhances your reflective, critical, and systems thinking perspectives as powerful tools required to participate in changing the world.

We draw upon an existing knowledge bank to transfer skills to you via our Masterclasses, Online Courses or live online Workshops.

Here’s an overview of the 8 key skills you’ll gain and why they’re so crucial for any creative change-maker’s toolkit:

1. Problem Framing

Here at The UnSchool, we love love love problems and all of the brain-stretching fun that comes along with understanding what makes them tick. We’ll teach you how to love them as well (and encourage you to sleep and eat your veggies to help that brain stretching!).

You’ll learn how to write problem statements and frame your change initiatives as creative quests so you can quickly get to the heart of what it is you’re seeking to change.

Great classes that will help you gain this right now are Make Change, Research Strategies and Project Activation and Amplification.

2. Systems Thinking

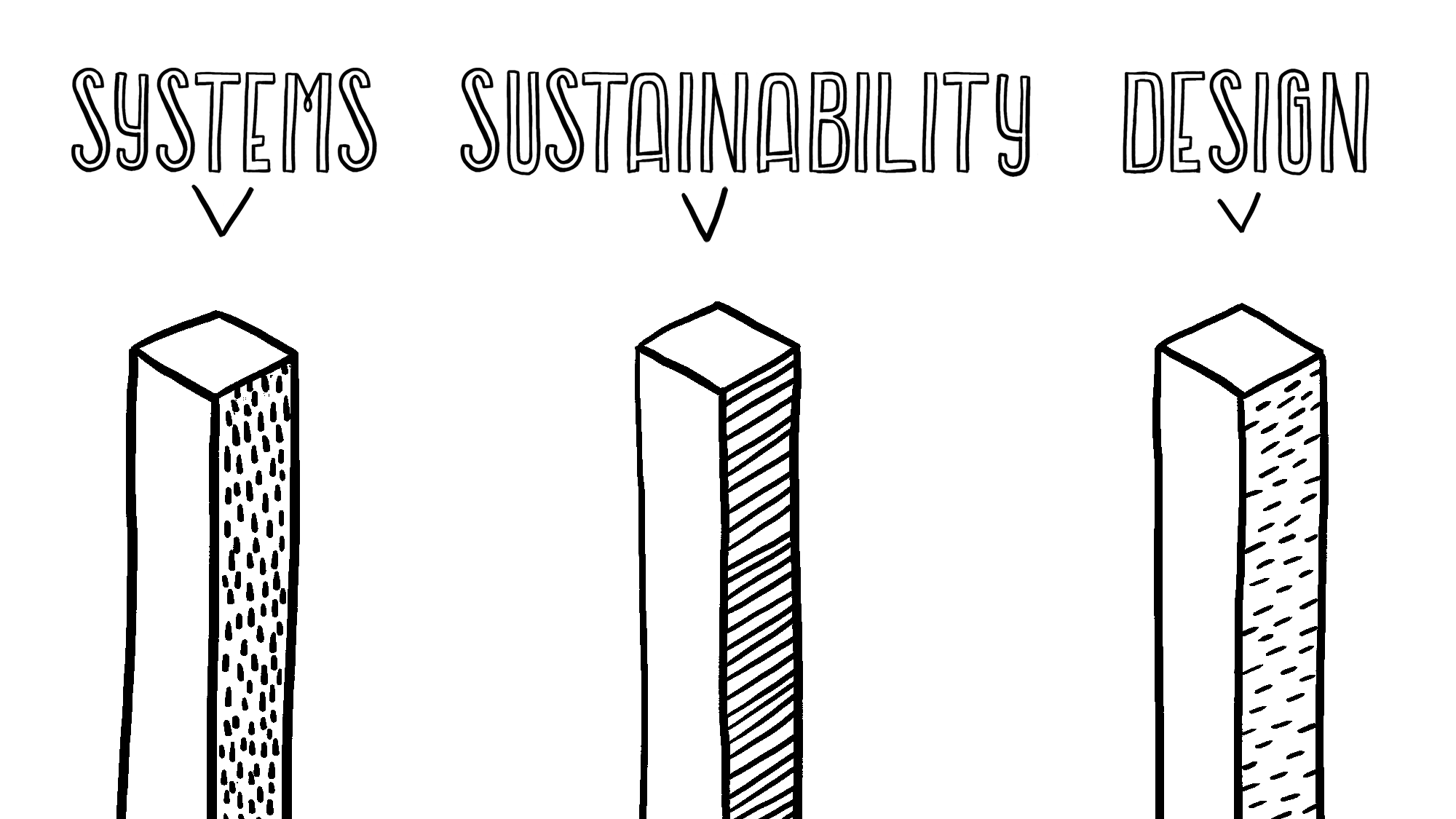

A core component of the three pillars of our philosophy (systems, sustainability and design), is the power of systems thinking. It is unmatched in creative change-making and a fundamental part of any good practice.

Everything is interconnected, and in order to leverage creativity while making change — actually, in order to do just about anything — one needs to know how to see, identify, interact with and think in systems.

Take our very popular Systems Thinking course or get started with our Introduction to Systems Mapping. More advanced players can take our Systems Intervention course.

3. Systems Mapping

When it comes to making change, knowledge without application isn’t very useful. So while thinking in systems is a great start, applying a systems mindset to designing interventions is where the real magic lies.

To help you put your systems thinking knowledge to work, we’ll teach you how to map systems via various tools like cluster maps and interconnected circles maps (and later, how to design sustainable interventions based on the insight you glean from those maps!).

Get started with Introduction to Systems Mapping, or read our e-books Design Systems Change or Circular Systems Design.

4. Life Cycle Thinking

Similar to systems thinking, you’ll uncover the secret lives of everyday things when you begin viewing them from a life cycle perspective.

We’ll show you how to easily map the production flow and material impact of anything created, as well as show you how to access life cycle data to give you the skills to do quick, paper-based life cycle explorations for comparing products and services.

We cover this in detail in our Sustainability in Business 101 course and in our Introduction to Life Cycle Thinking course.

5. Theory of Change

A Theory of Change is an approach to setting actions to get outcomes that you can map. You could say it is a description, or illustration, of the approach you would take to enact change, and it can be done both for an actual intervention or for an entire philosophy on how change happens.

We will show you how to reverse engineer your change objective by using the theory of change methodology. This is an incredible way to not only lay the pathway for change but also develop a benchmark for measuring change initiatives in the future.

Jump into the wonderful world of making change with our Make Change course, or level up your change initiatives with our Project Activation and Application course.

6. Circular Design

We are all consumers in the current linear economy, but as we transition to one that massively reduces waste and instead promotes a variety of reuse approaches, we will each become shareholders in the delivery and cycling of goods and services throughout the economy.

The Circular Economy requires a redesign of nearly everything, so we’ll equip you with all the circular design (and redesign) tools and strategies you need to be apart of this global transformation.

Get reading with our Circular Systems Design e-book, download our FREE open-source Circular Redesign Toolkit or take our Introduction to Circular Economy Class to advance your capacity in this important skill.

7. Gamification Design

Gamification is the use of game mechanics in non-gaming environments, and it has become the hot tool for user experience design. It is a technique of dissecting and exploring the mechanics that motivate action in non-gaming environments — and it can truly be a ‘game changer’ when it comes to making creative change (say that 3x fast!)

You will learn all about the mechanics of gamification, the different ways you can apply it to effecting change and the fascinating world of human behavioral motivators.

We have a course in Gamification and Game Theory that covers everything you need to know! If you are already into gamification, then take our Cognitive Science and Bias course to learn more about the behavioral patterns around this.

8. Activation Planning

Pulling it all together, your activation plan is the last step before you launch your creative change idea into the world. This helps you feel confident and prepared to do what you set out to do: change the world.

We show you the tactics and practical ways of turning an idea into action and ensuring that it has sustainable, long-lasting impact.

Our Project Activation and Amplification course is the perfect place for you if you want to get your change-making ideas out into the world. We also have a 30-day activation challenge that is perfect for you if you are keen to effect change and want to learn ALL THE TOOLS!

Many of these tools can be found outlined in our FREE toolkits. You can access them suit of them here >

If you’re ready to make it happen, join us for our first live online Masterclass of 2021, The Disruptive Design Masterclass!

Taught over the course of 1 full month, you will cover one of these toolsets via 2x weekly live sessions with a cohort of like-minded creative change-makers.

Want to know what the experience is like? Check out Alumni Milosz’s experience here.

What is Disruptive Design?

By Leyla Acaroglu

Disruption was asked to be banished in 2012, 2014, and 2015, yet it still is a hot, overused ‘buzzword.’ Just like many aspirational terms before it (like sustainability and innovation), popularity leads to overuse, dilution, confusion, and fatigue. Frankly, overuse sucks the meaning right out of a concept until it’s just a shell of an idea held together by ink on a page.

Disruption, like so many overused words, is intensely misunderstood. While conceptually the term means to create an interruption into something that is maintaining a status quo, colloquially it is much more about making loads of money from the newest, most ‘disruptive’ (read: newer) technology out there. It’s toppling old industries through new smart, young, and agile upstarts. In this context, it’s not about making change; it’s about winning customers, clicks, and clients.

To disrupt is to disturb or intervene. The term came to prominence in the late 90s when Clay Christensen, an MIT professor, spoke of it in relation to business activity in his book The Innovator’s Dilemma. For Christensen, his term “disruptive innovation” is the very specific act of challenging a mainstream company by creating a new parallel product that activates previously un-activated elements of the economy; thus, it creates a shift toward the new offering, poaching consumers from the main player over to the newer innovation. It has nothing to do with coolness or edginess, or even social change or sustainability. Disruptive innovation, in this context, simply has to do with new economic activity that challenges the mainstream business establishment.

Christensen has written about how Uber, often referred to as a major disrupter, is indeed not a disruptive innovator. According to his theory, Uber misses the mark because it did not enter a low-end or new foothold market; instead, it launched in San Francisco, a place where taxi rides were already in high demand and its target audience was already accustomed to using taxis. Furthermore, Christensen points out that the term disruptive is being wrongly used to describe innovation that is simply improving upon a good product that already exists - something Uber did masterfully by offering convenience for hailing a cab and paying for it via a smart app.

But, for Christensen, they missed the mark on being disruptive because the initial consumer base did not reject it and wait for its quality to improve in order to drive down market prices; instead, those already using taxis happily thrust Uber to the top of the market. So yes, Uber is transforming the taxi industry, but, according to Christiansen’s framing of disruption, their business model does not follow the basic principles to qualify it as “disruptive.”

The Case for More Disruptive Design

So, where does disruptive design come into play? And can it really be differentiated from disruptive innovation? While the concepts have similarities on face value (such as shared a word that describes change), disruptive design is very different from the concept of disruptive innovation.

Here’s how I frame it:

Design is the act of creating something new — sometimes iterative, sometimes innovative, and in rare cases, revolutionary. Designing is an intentional act of creating a product, service, or system that embodies some degree of change. First and foremost, design has to achieve function (purely aesthetic creative productions are not, in my opinion, design; they are more so in the world of art, which is incredible and valuable and all of the adjectives to describe the power of art and yes there is always a need for more of it in the world). But art can exist without function whereas design can’t, so when we talk about Disruptive Design, we are talking about creating intentionally disruptive creative interventions that are functionally imbued with the objective of challenging the status quo and making positive change.

Design is about creating something that adds to or iterates on the existing, and disruption is about creating a disturbance with the intent of changing a system. When combined, the practice of disruptive design is to create intentional interventions into a pre-existing system with the specific objective to leverage a different outcome, and more importantly, an outcome that is likely to create positive social change.

When combined, the practice of disruptive design is to create intentional interventions into a pre-existing system with the specific objective to leverage a different outcome, and more importantly, an outcome that is likely to create positive social change.

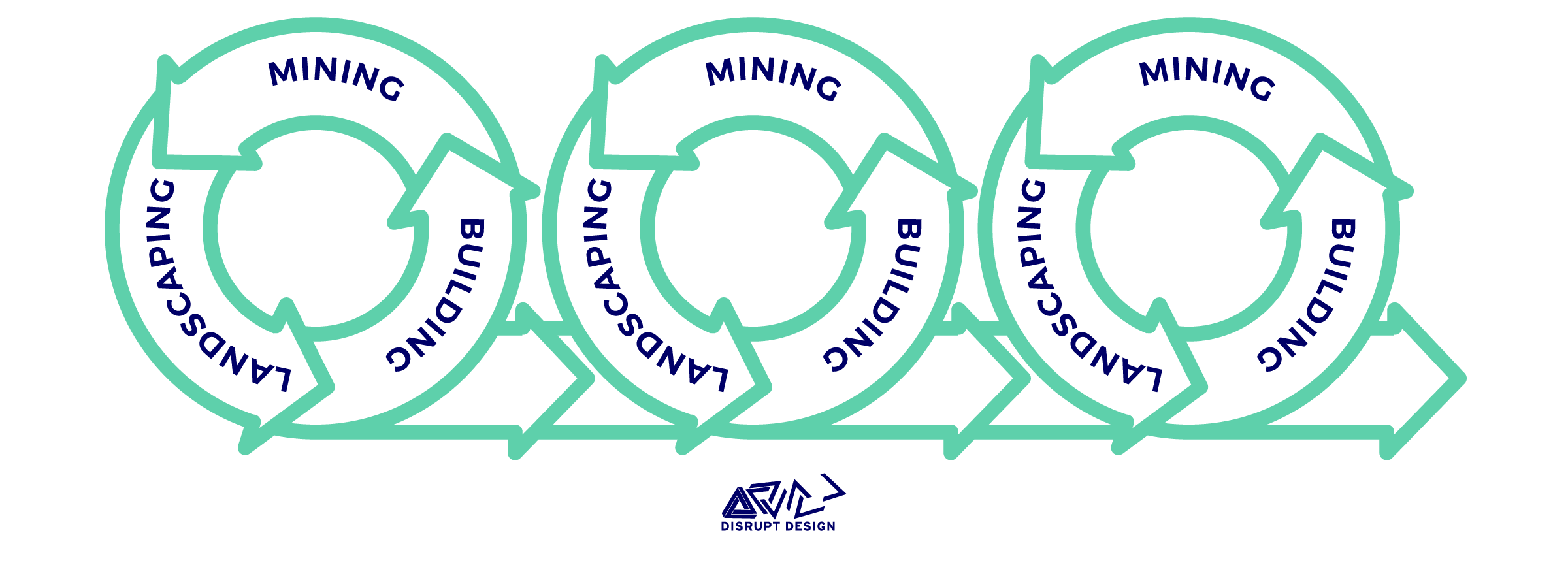

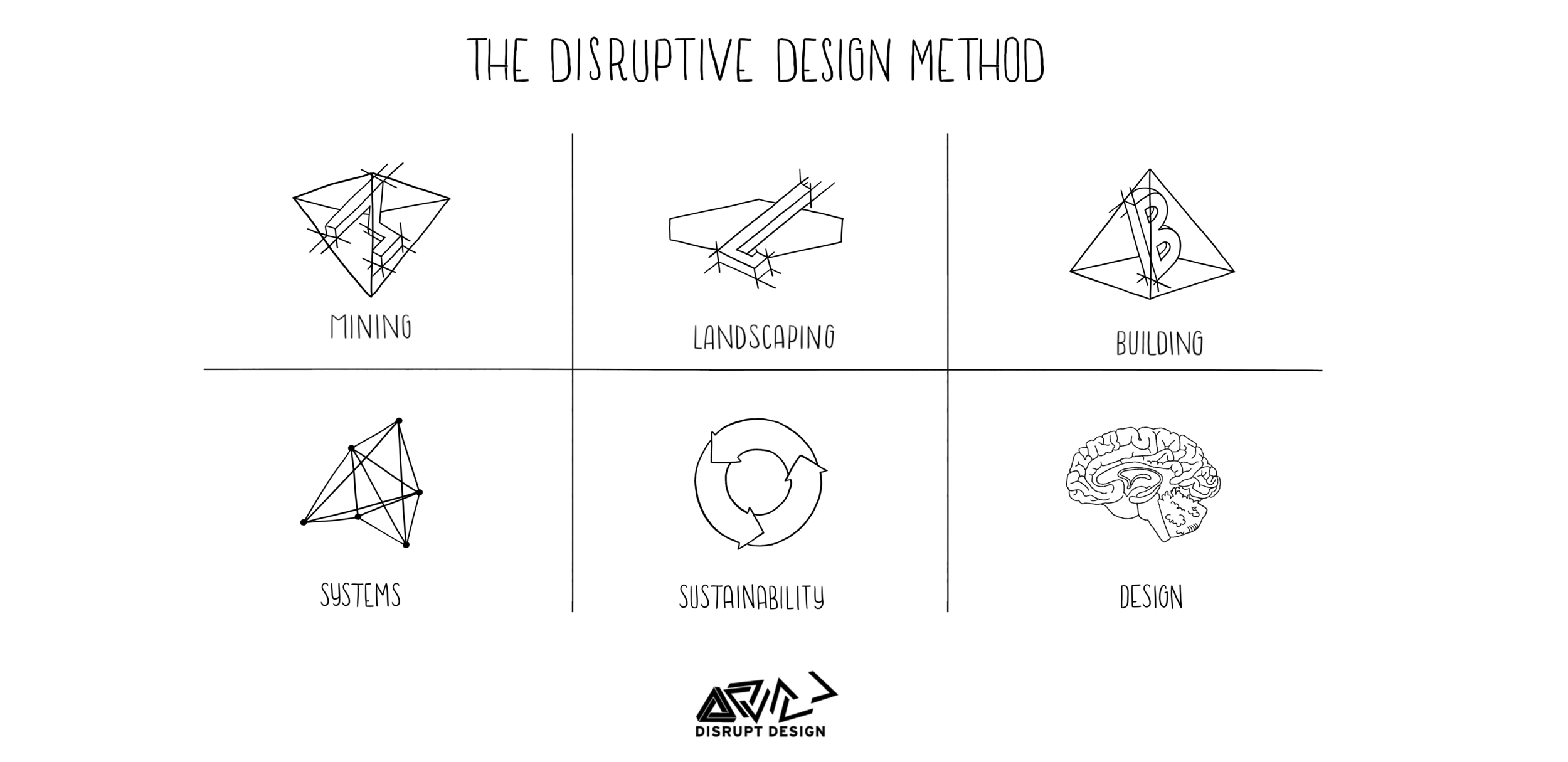

The Disruptive Design Method (DDM) is about activating sustainability principles through creative practice. It employs a series of thinking and doing tools that anyone can implement in a formulated processes of mining, landscaping, and building to develop a three-dimensional perspective to exploring, understanding, and intervening in complex hyper-local to global problems.

Mining: Deep dive into the problem, develop research approaches, explore the elements within: PROBLEM LOVING STAGE.

Landscaping: Identify the main elements in the system and map how they interact, relate and connect: SYSTEMS MAPPING STAGE.

Building: Solutions emerge from the last two stages. Explore options, viability and possibility. Test, prototype, repeat: IDEATION & INTERVENTION STAGE.

I developed the Disruptive Design Method as a way to fill a gap between knowledge and action, to forge a community of practice that facilitates purpose-driven changemakers, to activate systems thinking, to consider sustainability sciences in what we produce and to enhance creative ideation techniques as platforms for actively participating in the world around us. Really, it’s a remedy for the perpetual frustration that many of us experience, as it provides a set of mental and practical tools to help redesign the world so that it works better for all of us.

We live in a hyper-negativity-fueled media landscape where it is increasingly difficult to escape the perception that everything is fucked. But if we all opt into this restrictive mental model, then we are opting into a self-perpetuating future. In fact, the future is not defined; we co-create it as we participate in the construction of what is relevant now. Our immediate actions actually define the future scenario that we will be in, both individually and as a collective whole (there is so much amazing nerdy stuff out there ATM on this from physicists; see here, here and here).

“The best way to predict the future is to design it” — R. Buckminster Fuller

What may be most surprising about Disruptive Design is that it is not limited to designers, engineers, techies, entrepreneurs, or any other profession that’s been unconsciously linked to the word “disrupt.” Anyone can practice the Disruptive Design Method:

Here are the general prerequisites:

Give a shit about the future of this planet

Have a burning desire to participate in designing solutions that address hyper-local to global issues that affect humanity and the sustainability of the life-support systems that sustain the planet

Be open to sharing, exchange, and collaboration

Be a pioneer who is willing to fail, discover, curiously explore, and change a core part of what they do in the world

See problems as opportunities

REthinking linear consumption

Our entire economic structure is based on the idea of producers and consumers. Whilst we know it’s a little more complex than this dichotomic bi-structure, there are very specific differences in these two approaches to living in this world. Modern lifestyles are geared toward a massive shift in production to consumption. Consumption is the act of passively absorbing the products of society, whereas a producer is an agent that forms the artifacts and elements that make up the human world. All elements of an ecosystem designed by nature are both producers and consumers.

Humans are the only species that create closed ecosystems, where one is reliant on the dictatorship of the creator. I can imagine you are reading this on a product that is created as a closed ecosystem, designed to create an addictive need for the specific products of the creator.

How does this relate to being a disruptive changemaker? It’s easy; avoid being a passive consumer, activate your agency, and become an active producer. The hard part is that it requires a rewriting of the mental codes we have all become comfortable with and are attached to for convenience and efficiency alike.

Creativity has always been about challenging the status quo. The advent of the industrial revolution came along and really helped shift the role of creativity, industrializing its role in society. When the profession of industrial design was created, it was all about customizing the user experience to overcome the mundanity that mass production had facilitated. Also, companies now needed to find new ways of getting a competitive edge, and creatives started to be the hot commodity in facilitating this need (a trend we are also seeing again on the rise now with the Internet age). Inherently, though, design, in this context, was focused on adding to the aesthetic experiences of the material world and its rapid advancement; it wholeheartedly embraced issues of planned obsolescence and the advent of the throwaway culture (there are troves of old-school reading on this; here are a few great starting points- Vance Packard’s The Waste Makers, Gils Slade’s Made to Break and The Economist’s Planned Obsolescence).

Now we have experience design (in which many jobs are filled by traditionally trained industrial designers), and it’s really about cognitive experience design (Tristan Harris, who used to be a Design Ethicist at Google, writes about this in this article). The issue here is that the designed world is often created to serve the interests of corporations as producers, to activate the latent consumer desires. Creative minds are put to work on creating the financial and neurological dependence of the average human to be addicted to the momentary emotional benefits that consumption has on us. Just take the pure emotional joy that many of us experience the moment we get a new gadget — the bliss that a well-designed UX offers us — and compare it to the pain and frustration that we experience when something does not work according to our expectations. And then as quick as it sets in, it wears off, because — here’s where the money factor comes in — so much of what is produced is designed to break, to be undesirable as quickly as it was desired!

This is where the Disruptive Design Method differs from the rest. It means actively seeking out the production of goods, services, and expenses that challenge and change the status quo so that we have more significant contributions to the narratives of where we want to end up as a species, happening from all sides of the debate. And this means corporations must be willing to experiment and create things that go against the “business-as-usual” model of take, make, use, and dispose. This is where movements like the circular economy, regenerative business, and product-service-system models are so incredibly powerful at reimagining the economic activities that sustain many of our livelihoods, but also have significant costs to the wider social and environmental ecosystems.

Activate your Agency: Learn the Disruptive Design Methodology

The Disruptive Design Methodology is a three-part process of mining, landscaping, and building for problem solving that helps people develop a three-dimensional perspective of the way the world works and provides a unique way of exploring, identifying, and creating tactical interventions that leverage systems change for positive social and environmental outcomes.

Because intervening in the status quo requires a critical and flexible thinking framework (along with a bit of rebellious flare), the Disruptive Design approach initiates change by teaching practitioners to love a problem arena, which essentially is any arena in which you wish to create positive change. Instead of avoiding or ignoring problems, the Disruptive Design method dives right into the sticky center of the issue and then looks at the ways in which complex, dynamically-evolving systems interact in order to find the opportunities for leveraging change through creative interventions.

Once you learn to be a problem lover, you use systems boundaries to define the spaces you wish to explore, and then find connection points perfect for a tactical intervention (which is often not where you would intuitively think, based on your starting knowledge in the problem arena).

Then, because you have all this new knowledge from mining and landscaping, you can rapidly develop divergent solutions and creative approaches for change that builds on your unique individual sphere of influence, which is the space we can all curate to affect change on the people or things around us. Any problem from community concerns to massive global crises can be explored and evolved through this method; because it’s a thinking and doing practice, it can be adapted and evolved based on the problem. The core pillars of the approach are always systems, sustainability, and design.

Disruptive Design is a way for creatives and non-creatives alike to develop the mental tools to activate positive change by mining through problems, employing a divergent array of research approaches, moving through systems analysis, and then ideating opportunities for systems interventions that amplify positive impact through a given micro or macro problem arena. It enables you to gain an empowered perspective of your role in the world and get the tools to take on a proactive approach to designing change in everyday local environments and socially-motivated practices.

The entire knowledge set equips you to be a more aware and intentional agent for change. You can dive into a comprehensive overview of the Disruptive Design Methodology in this online introductory class, or you can also download this FREE toolkit for creative facilitation using the Disruptive Design Method!

Quick Guide to the Disruptive Design Method

By Leyla Acaroglu, Originally published on Medium

The Disruptive Design Method (DDM) is a systems-based approach to creative problem solving for tackling complex social and environmental issues. It combines sociological inquiry methods (mining) with systems explorations (landscaping) and design and creativity (building) approaches. The method is built on systems, sustainability and design, allowing for a three-dimensional perspective shift of a problem arena to ensure that interventions create positive change. Here we cover a quick guide to the DDM.

We live in a complex interconnected world riddled with dynamic and often chaotic problems that requires a mindset and skillset shift in order for us to address them at a systemic level.

The Disruptive Design Method is an approach to problem-solving that helps develop a three-dimensional perspective of the way the world works, and provides a unique way of exploring, identifying, and creating tactical interventions that leverage systems change for positive social and environmental outcomes.

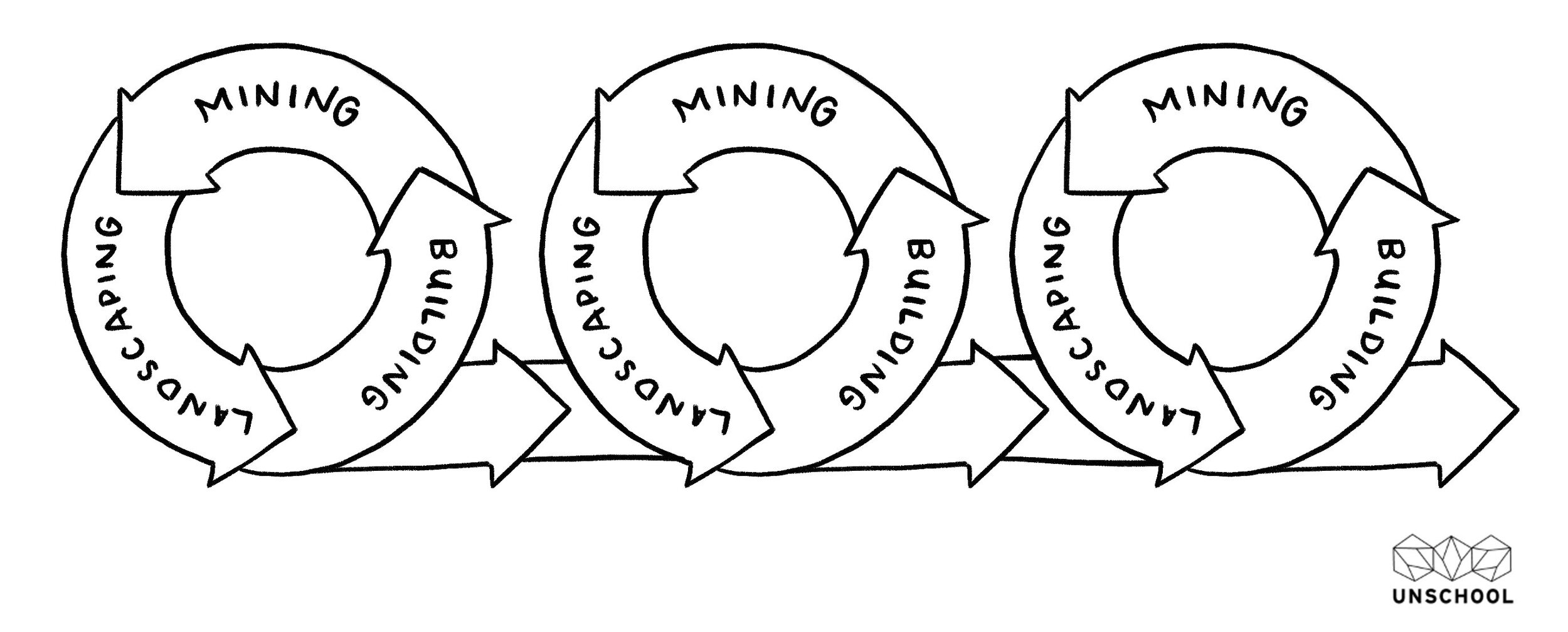

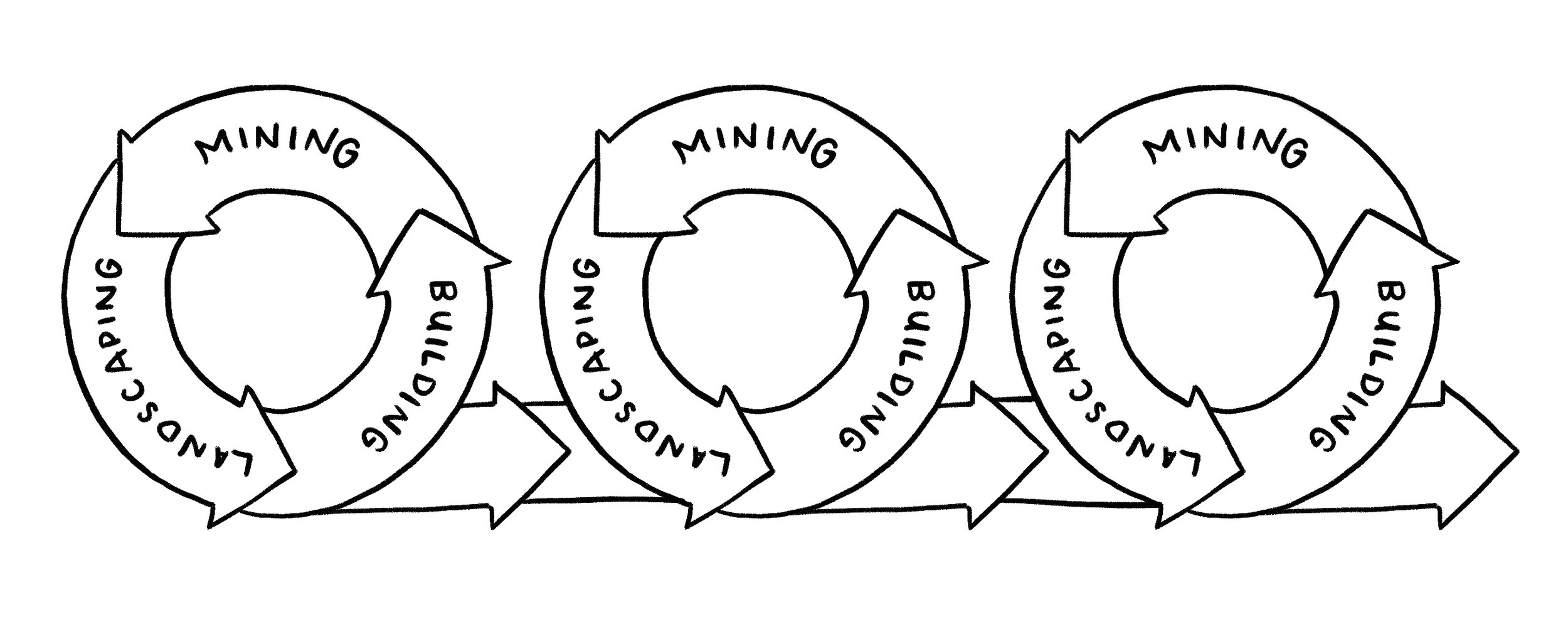

The three-phase process of Mining, Landscaping, and Building (MLB) is cycled through to create outcomes that are creative and sustainability-focused. This approach offers a micro-to-macro-and-back-again perspective of the problem arena in which you wish to create positive change within and supports the development of a more three-dimensional worldview.

The three phases of the Disruptive Design Method: Mining, Landscaping and Building

In this quick guide, I explain the what, why, and how of the DDM, along with ways it can help create non-conventional approaches to addressing complex problems, such as those presented by the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

We use systems boundaries to define the spaces we wish to explore, and then find connection points perfect for a tactical intervene (which is often not where you would intuitively think, based on your starting knowledge in the problems arena). Then, because we have all this new knowledge from mining and landscaping, we can rapidly develop divergent and creative approaches to intervening in the systems the create change.

Any problem from small, hyper-local concerns to massive global issues can be explored and evolved through this method, and because it’s a thinking and doing practice, it can be adapted and evolved based on the problem. The core of the approach is always systems, sustainability, and design.

POSITIVELY DISRUPTIVE BY DESIGN

Design is an incredibly powerful tool that changes the world. Everything around us has been constructed to meet the needs of our advanced human society, and in turn, our individual experiences of the world are influenced dramatically by the designed world we inhabit.

We are each citizen designers of the future through the actions we take every day, which is why I developed the DDM as a systems-based creative intervention design method for exploring and actively participating in the design of a future that works better for us all.

Intended as a way for creatives and non-creatives alike to develop the mental tools needed to activate positive change, the DDM approaches creative problem solving by mining through problems and employing a divergent array of research approaches, moving through to landscaping the systems at play and identifying the connections and relationship dynamics that reinforce the elements of the system, and then ideating opportunities for systems interventions that amplify positive impact by building new ideas that shift the status quo of the problem at a systems level. This is then cycled through in an iterative way until the outcome is tangible and effective at altering the state of the issue at hand.

The DDM is an iterative process

As Buckminster Fuller teaches, often the smallest part of the system has the capacity to make the biggest change — and that’s one of the fundamental approaches that the DDM enables: identify the part within the system that you have agency and ability to impact.

Instead of avoiding or ignoring problems, we teach you how to be problem lovers who dive right into the sticky center of the issue; then, you will get busy designing divergent solutions that build on your unique individual sphere of influence, which is the space we can all curate to affect change on the people or things around us. Your personal sphere of influence will grow and ebb and flow over time.

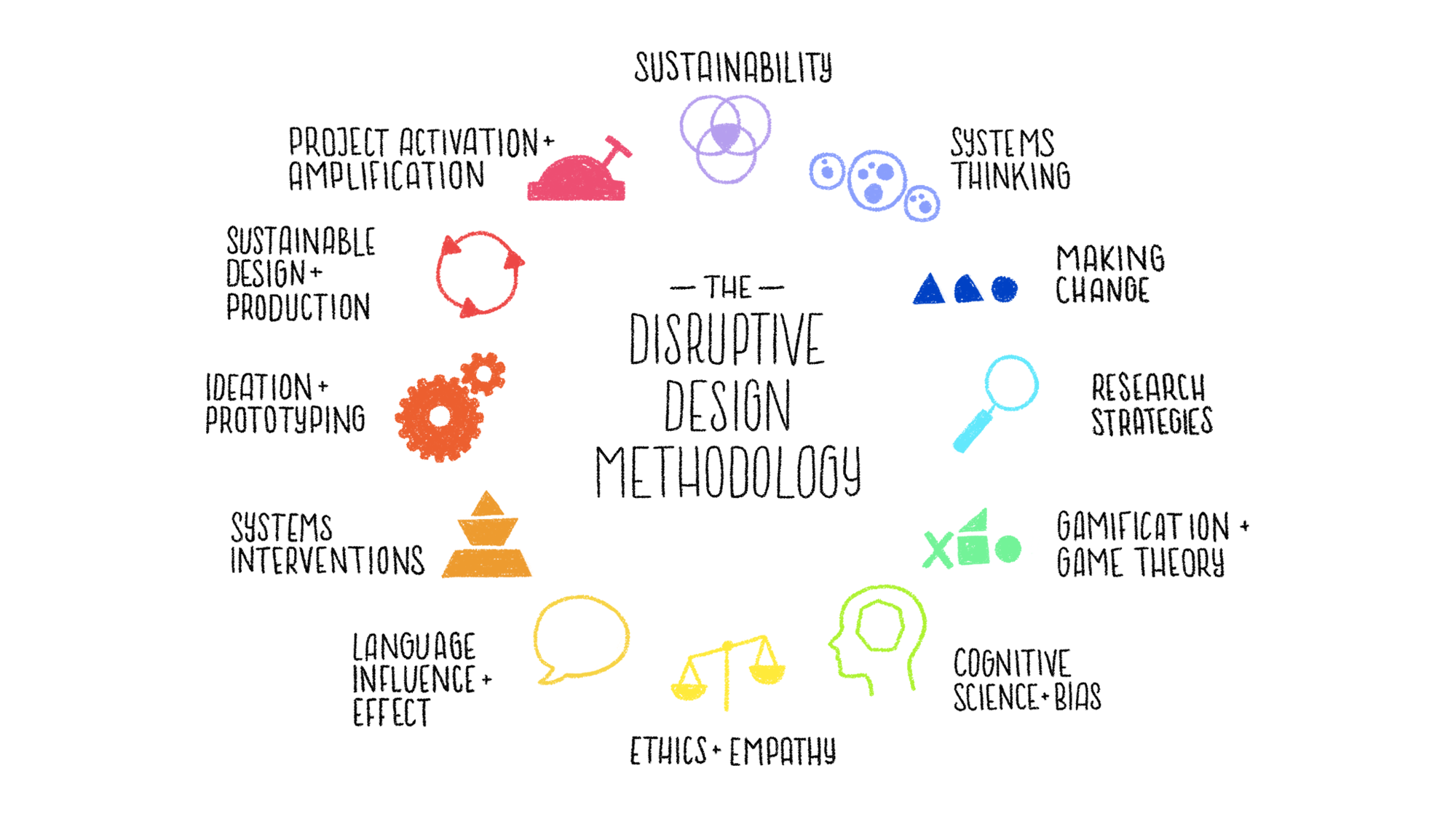

Additionally, the DDM includes a 12-part knowledge set that, when explored as a whole, equips anyone with the thinking and doing tools to be a more aware and intentional agent for positive change. It also has the tools to cycle through the issues and seek out the non-obvious opportunities, designing divergent interventions and solutions that build on your unique individual sphere of influence. These are topics of self-development explored in my latest handbook Design Systems Change and through my 30-day Challenge.

Perhaps most importantly though, instead of avoiding or ignoring problems, this method offers up tools for shifting perspectives that enable one to become a problem lover with the ability to dive right under the obvious parts of the issue at hand, avoid laying blame, and instead, identify and uncover the parts of the system that reinforce the issue so that change can be created.

In a world where many people see and feel problematic impacts with intensity — the social, environmental, and political issues especially — and then become overwhelmed or disabled by this complexity, we see good-intentioned people disengage from taking action. Thus, I can not understate how powerful seeing problems through the lens of opportunity, optimism, and yes, even a bit of love can be for someone. I want to provide an agentizing effect, a set of tools that enable people to move from overwhelming problems to possible actions; after all, the world is made up of the accumulation of individual actions of many, you and me included.

Problem loving is the DDM mindset

THE ORIGINS OF THE DDM

When I first started to develop the Disruptive Design Method, it was in part a reaction to the one-dimensional problem-solving techniques that I had been taught through my years of traditional education. Back in 2014, as I was finishing my PhD and preparing to launch the UnSchool of Disruptive Design, I knew that there needed to be a scaffolding that would support all the content I wanted to fill this experimental knowledge lab with. Drawing on the years of professional experience and research I had to date, I went about iteratively developing and refining the modules from 20+ down to 12 core components of the Disruptive Design Methodology set, a learning system that, once fully engaged with, fits together to create the DDM.

The 12 core modules of the Disruptive Design Methodology

It’s a ‘scaffolding’ because it’s not intended to be rigid and formulaic, but instead, it offers the support that one needs as they start to develop a more three-dimensional view of the world and adopt the skills of systems thinking, problem exploration, and creative intervention design. I personally use this approach in all the commissions and collaborations I do, like in designing learning systems for Finland and Thailand, and in creating sustainable living initiatives, like the Anatomy of Action with the UNEP.

A scaffolding is often used to create support around a building as it is going up — it’s the skeleton structure that enables the progression up into the air. This is the intention with the DDM, to offer support as a 3D worldview and mindset is developed to overcome reductive thinking and create a more robust set of tools that enable a problem-loving approach to solving complex real-world problems.

I, along with my team, have taught the DDM and the core approaches of systems and life cycle thinking to thousands of people all over the world, from teenagers to CEOs, with hundreds of alumni completing our in-person programs and thousands enrolled in our online school. We have seen many different incarnations of the DDM and its tools in action throughout our five years of running the UnSchool and its various programs.

The world needs more pioneers of positively disruptive change — people equipped with the thinking and doing skills that will enable them to understand and love complex systems and then be able to translate that into actual change. There are, of course, many tools and approaches for designing change, and the DDM is just one of a wide suite of tools out there. I am an appreciator of many of them, but for me, the reason why anyone should gain an overview of this approach is that it combines the three pillars of systems, sustainability, and design, of which I have not seen an approach yet to do the same.

What this all boils down to is having a unique method on hand to positively intervene and disrupt the status quo of any problem arena to ensure that the outcome is more effective, equitable, circular and sustainable. That’s why we always offer equity access scholarships and ensure that people from all walks of life can gain access to these valuable perspective-shifting tools we offer at the UnSchool.

THE 3-PARTS OF DISRUPTIVE DESIGN METHOD

There are three distinct parts of the Disruptive Design Method — Mining, Landscaping, and Building (MLB) — each is enacted and cycled through in order to gain a granulated, refined outcome through iterative feedback loops.

The first part is Mining, where the mindset is one of curiosity and exploration. In this phase, we do deep participatory research, suspend the need to solve, avoid trying to impose order, and embrace the chaos of any complex system we are seeking to understand. The tools of this phase are: research, observation, exploration, curiosity, wonderment, participatory action, questioning, data collection, and insights. This can be described as diving under the iceberg and observing the divergent parts that enable us to understand a problem arena in more detail.

The second stage is Landscaping. This is where we take all the parts that we uncovered during the Mining phase and start to piece them together to form a landscaped view through systems mapping and exploration. Landscaping is the mindset of connection, where you see the world as a giant jigsaw puzzle that you are putting back together and creating a different perspective that enables a bird’s eye view of the problem arena. Insights are gathered, and locations of where to intervene in the system to leverage change are identified. The tools for this phase are: systems mapping (cluster, interconnected circles, etc.), dynamic systems exploration, synthesis, emergence, identification, insight gathering, and intervention identification.

The third part of is Building. This is the creative ideation phase that allows for the development of divergent design ideas that build on potential intervention points to leverage change within the system. The goal is not to solve but to evolve the problem arena you are working within so that the status quo is shifted. Here we use a diversity of ideation and prototyping tools to move through a design process to get to the best-fit outcome for your intervention.

The key to this entire approach is iteration and ‘cycling through’ the stages to get to a refined and ‘best-fit’ outcome. Why do we do this? Because problems are complex, knowledge builds over time, and experience gives us the tools to make change that sticks and grows. This cycling through approach draws upon the Action Research Cycle to create an iterative approach to exploring, understanding, and evolving the problem arena.

The three applied parts of the MLB Method are based on a more complex Methodology set. This set combines 12 divergent theory arenas to form the foundation of identifying, solving, and evolving complex problems, as well as helps develop a three-dimensional perspective of the way the world works. From cognitive sciences to gamification and systems interventions, the 12 units of the Disruptive Design Methodology are designed to fit together to form the foundations of a practice in creative change-making.

THE FOUNDATIONS: SYSTEMS, SUSTAINABILITY, AND DESIGN

The UnSchool is deeply rooted in a foundation of applied systems, sustainability, and design, forming three knowledge pillars that hold up all we do — including leveraging the Disruptive Design Method.

The three pillars of the UnSchool and DDM

Whenever we teach a program, we always begin with systems thinking as the foundation, as it is one of the most powerful tools that we can use to address complex problems. It enables any practitioner to see how everything is interconnected, and systems can be viewed from multiple perspectives, allowing a shift from rigid to flexible mindsets. We also engage with the principles of sustainability through each phase, which for us, means doing more with less, understanding how the planet works so that we can work within its means, and evolving from an extraction-based society to a circular and regenerative one.

Through the Mining phase, systems boundaries are used to define the problem arenas that one wants to explore. Through systems mapping, research techniques, observation and reflection, all the parts that make up a system and their connections are explored through the landscaping phase, laying the groundwork for exposing unique places to intervene (which is often not where you would intuitively think, based on your starting knowledge in the problem arena).

From this, new knowledge is built from the Mining and Landscaping phases, which forms the foundation for the Building phase — rapidly designing divergent and creative ideas to intervening in the problem arena. Any problem from small, hyper-local concerns to massive global issues can be explored and evolved through this MLB Method. And, because it’s equally a thinking and doing practice, it can be adapted and evolved based on any problem. The core of the approach is always systems, sustainability, and design.

HOW THE DISRUPTIVE DESIGN METHOD HELPS MAKE POSITIVE CHANGE

LOVING THE PROBLEM

Many people avoid problems, which means that they never truly understand them. By learning to love problems and see them as opportunities in disguise, you will develop an open mind that thinks differently. This is all about being curious and trying to understand something before you attempt to solve it! The more curiosity you can foster, the more things you will uncover about the world around you.

SEEING RELATIONSHIPS

Everything is interconnected, and actions create reactions. Being able to see the relationships that make up cause and effect are part of any good problem solvers tool belt. The content of the DDM is designed to foster systems perspectives as well as deep identification with cause and effect relationships.

PERSPECTIVE SHIFTING

The ability to see the world through other people’s eyes is critical to building resilience, empathy, and leadership skills. You will uncover how to constantly reflect and explore the world from diverse perspectives, overcome biases and be able to put yourself in the shoes of others to understand why people think or behave differently to you based on their own life and learning experiences.

COLLABORATION

Respectfully and successfully working with others, despite differences, is critical to creativity and leadership skills. The goal is to encourage people to see that diversity in collaboration is just as important as agreement, and that coming to a consensus can be achieved in many different ways. Many of the tools we teach, such as systems mapping, can be used as brilliant collaboration tools, so you gain incredible opportunities to foster effective collaboration.

At the UnSchool, we approach making change as a state of being; we believe that being change-centric is a way of defining a life agenda, finding purpose, and setting the tone for how you live and contribute through your life and work. We all have the power to affect positive social and environmental change in and through everything we do, from the things we buy to the conversations we have and the kind of work we do. This change-centric approach is by all means a cultivated one in which you have to work at wanting to make change. Because truly, it’s not always easy; in fact, trying to make change can definitely hurt sometimes — and frankly, it often requires some measure of failure along the way. How would we have evolved as a species had we not experienced millions of years of failure and accidents? Allowing the space for failing early on creates better, stronger results later. In saying this, it should also be noted that change is one of the easiest things to make happen… if you have the right tools and resources, which are built into the DDM.

You can take the full program at your own pace via our online school here, or if you do a certification track, you get access to the full 12 modules, plus loads of extra content on activating and facilitating change.

A Quick Guide to Sustainable Design Strategies

By Leyla Acaroglu, Originally published on Medium

Sustainable design is the approach to creating products and services that have considered the environmental, social, and economic impacts from the initial phase through to the end of life. EcoDesign is a core tool in the matrix of approaches that enables the Circular Economy.

There is a well-quoted statistic that says around 80% of the ecological impacts of a product are locked in at the design phase. If you look at the full life cycle of a product and the potential impacts it may have, be it in the manufacturing or at the end of life stage, the impacts are inadvertently decided and thus embedded in the product by the designers, at the design decision-making stage.

This makes some uncomfortable, but design and product development teams are responsible for the decisions that they make when contemplating, prototyping, and ultimately producing a product into existence. And thus, they are implicated in the environmental and social impacts that their creations have on the world. The design stage is a perfect and necessary opportunity to find unique and creative ways to get sustainable and circular goods and services out into the economy to replace the polluting and disposable ones that flood the market today. The challenge is which designers will pick up the call to action and start to change the status quo of an industry addicted to mass-produced, fast-moving, disposable goods?

For those that are ready to make positive change and be apart of the transition to a circular and sustainable economy by design, the good news is there is a well-established range of tools and techniques that a designer or product development decision-maker can employ to ensure that a created product is meeting its functional and market needs in ways that dramatically reduce negative impacts on people and the planet. These are known as ecodesign or sustainable design strategies, and whilst they have been around for a while, the demand for such considerations is even more prominent as the movement toward a sustainable, circular economy increases.

Sustainability, at its core, is simply about making sure that what we use and how we use it today, doesn’t have negative impacts on current and future generations' ability to live prosperously on this planet. Its also about ensuring we are meeting our needs in socially just, environmentally positive and economically viable ways, so its very much a design challenge. Consumption is a major driver of unsustainability, and all consumer goods are designed in some way.

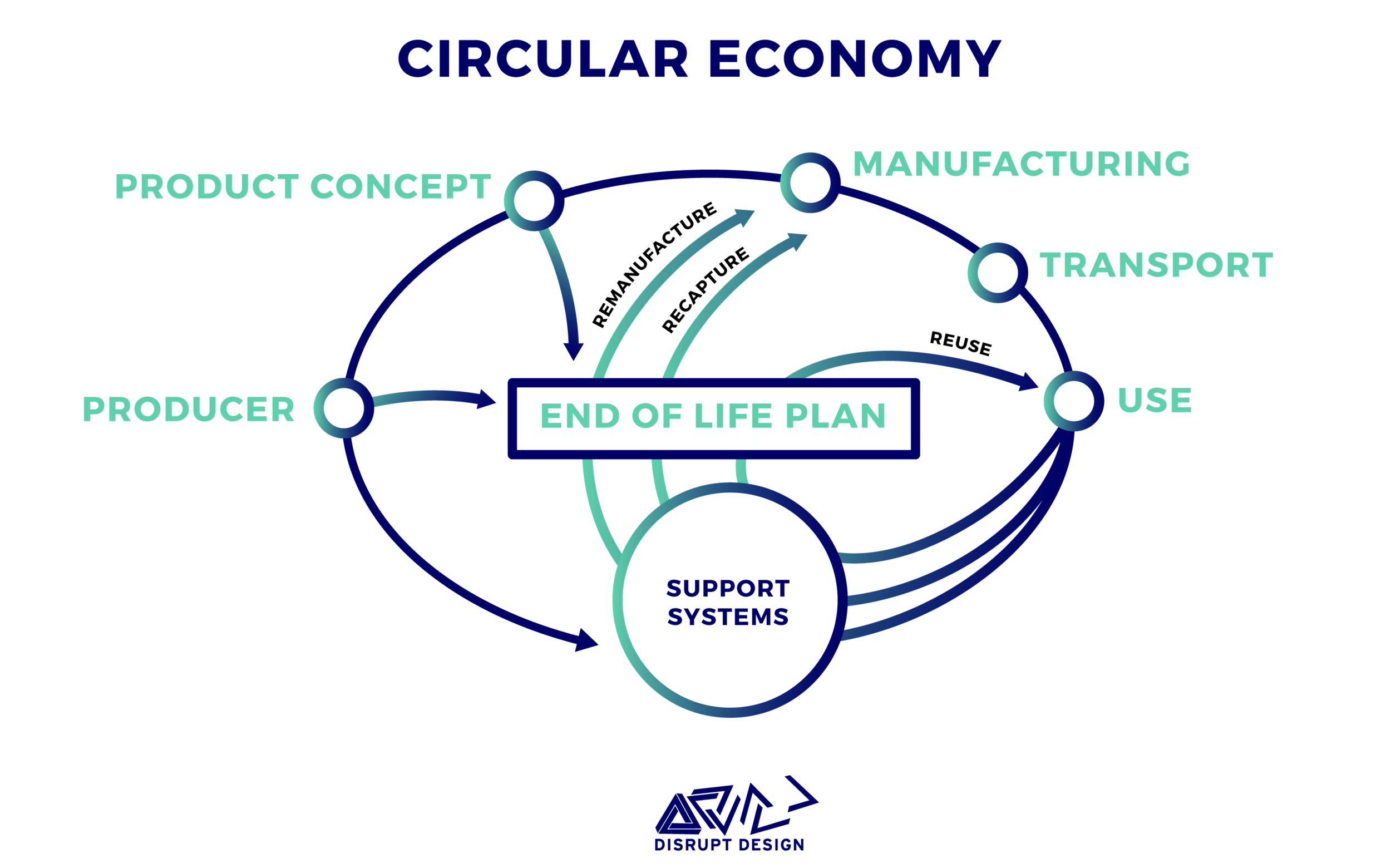

When sustainability is applied to design, it enlightens us to the impacts that the product will have across its full life cycle, enabling the creator to ensure that all efforts have been made to produce a product that fits within the system it will exist within in a sustainable way, that it offers a higher value than what was lost in its making, and that it does not intentionally break or be designed to be discarded when it is no longer useful. Provisions should have been made so that there are options for how to maximize its value across its full life cycle and keep materiality in a value flow. This is otherwise known now as the circular economy and the practice of enabling this is circular systems design.

Long before there was a Twitter hashtag devoted to all things sustainability, sustainable design pioneers like Buckminster Fuller and Victor Papanek were figuring out how to reduce the impact of produced goods and services through design. As the sustainability concept has evolved, so has the framework for the thinking and doing tools that we now can routinely integrate into our practices to help understand and design out impacts and design in higher value. I see sustainable design as one of the tools that we each need to employ in order to make things better, its the practical side of considering sustainability, connected to considerations around life cycle thinking, systems thinking, circular thinking and regenerative design. By understanding these approaches, a toolbox for change can be created by any practitioner to advance their ability to create incredible things that offer back more than they take. This should be the goal of any creative development.

The ecodesign strategy set for sustainable design includes techniques like Design for Disassembly, Design for Longevity, Design for Reusability, Design for Dematerialization, and Design for Modularity, among many other approaches that we will run through in this quick guide. Basically, the ecodesign strategy toolset helps us think through the way something will exist and how to design for value increases whilst also maintaining functionality, aesthetics, and practicality of products, systems, and services. It’s especially effective when applying materiality to any of the creative interventions you are pursuing in your changemaking practice, be it a designer or not. We have a free toolkit for redesigning products to be circular that also details all of these strategies, and more.

For decades, much progressive experimentation and exploration of ecodesign, cleaner production, industrial ecology, product stewardship, life cycle thinking, and sustainable production and consumption has occurred, which all led up to the current framing of a new approach to humans meeting their needs in ways that don’t destroy the systems needed to sustain us. Right now the framing is around creating a sustainable, regenerative, and circular economy, whereby the things we create to meet our needs are designed to fit with the systems of the planet and maintain materials in benign or beneficial flows within the economy, which requires businesses to change the way they deliver value and consumers to adjust their expectations around hyper-consumerism. Central to this success is the design of goods and services and that's where these strategies and designers' creativity fit in.

There have been thousands of academic articles and business case studies on a multitude of different approaches to sustainable and ethical business practices, demonstrating the strong and clear need for systems-level change. Contributions from biomimicry, cradle to cradle, product service systems (PSS) models, eco-design strategies, life cycle assessment, eco-efficiency and the waste hierarchy all fit together to support this approach to sustainable design.

The Circular Economy

Within the last 20 or so years, we have really started to feel the negative impacts of what's called the linear economy, where raw materials are extracted from nature, turned into usable goods, purchased and then quickly discarded usually due to poor design choices, inferior materials or trend changes (or the more insidious practice of planned obsolescence). Recently, there has been a great framing around the shift from linear to circular systems called The Circular Economy Framework, which combines a range of pre-existing theories and approaches. Moving to a circular economy (which embraces closed-loop and sustainable production systems) means that the end of life of products is considered at the start, and the entire life cycle impacts are designed to offer new opportunities, not wasteful outcomes.

Our interpretation of the value flows within the circular economy from the Circular Systems Design handbook.

You may be wondering — especially if you aren’t a designer — how can we integrate this into a creative practice to make a positive change? Well, here’s the thing, the approaches to understanding and reducing the impacts of material processes are really important to reduce the use of global materials and the ecological impacts of our production and consumption choices. This is what the circular economy movement is seeking to achieve: a transformation in the way we meet our material needs.

On top of that, these approaches are very empowering for non-material decisions — you start to see the ways in which the world works and can apply this thinking to different problem sets. Sustainable design and production techniques allow for reducing the material impact by maximizing systems in service design — thus, providing sustainability during both production and consumption.

From our free educational project, The Circular Classroom. Find out more here

EcoDesign Strategies

These sustainable design strategies are best known as starting off with Victor Papanek in the 1970’s and have been contributed to over the years by many different people and approaches. This curated life of ‘design for x’ strategies takes into consideration the circular economy and how they relate to closing the loop and dramatically changing economic models.

In this list I have curated, I have also included a few “negative” design approaches at the end to remind you what not to do, and how easy it is to accidentally do the wrong thing right, rather than the right thing a little bit wrong.

In order to achieve circular and sustainable design, some, or many, of these design considerations need to be employed in combination throughout the design process in order to ensure that the outcome is not just a reinterpretation of the status quo, but something that actually challenges and changes the way we meet our needs.

These approaches are lenses you apply to the creative process in order to challenge and allow for the emergence of new ways to deliver functionality and value within the economy. There are also separate considerations of the circularization process outlined in the next section.

Product Service Systems (PSS) Models

One of the main ideas of the circular economy is moving from single-use products to products that fit within a beautifully designed and integrated closed-loop system which is enabled through this approach. Think of alternatives to purchasable products such as leasable items that exist as part of a company-owned system or services that enable reuse. Leasing a product out — rather than selling it directly — allows the company to manage the product across its entire life cycle, so it can be designed to easily fit back into a pre-designed recycling or re-manufacturer system, all whilst reducing waste.

By transitioning away from single end-consumer product design to these PSS models, the relationship shifts and the responsibility for the packaging and product itself is shared between the producer and the consumer. This incentivizes each agent to maintain the value of the product and to design it so that it’s long-lasting and durable. PSS requires the conceptualization of meeting functional needs within a closed system that the producer manages in order to minimize waste and maximize value gains after each cycling of the product. Many of the circular economy business models are either based on this concept or create services that enable the ownership of the product to be maintained by the company and leased to the customer. But it’s critical that this is done within a strong ethical framework and not used to manipulate or coerce people, as this could also easily be the outcome of a more explorative version of this design approach.

Product Stewardship

In a traditional linear system, producers of goods are not required to take responsibility of their products or packaging once they have sold the product into the market. Some companies offer limited warranties to guarantee a certain term of service, but many producers avoid being involved in the full life of what they create. This means that there are limited incentives for them to design products with closed-loop end of life options. In a circular economy, producers actively take responsibility for the full life of the things they create starting from the business model through to the design and end of life management of their products.

Product stewardship and extended producer responsibility are two strong initiatives that encourage companies to be more involved in the full life of what they produce in the world. There are several ways that this can occur; in a voluntary scenario, companies work to circularize their business models (such as a PSS model) or governments issue policies that require companies to take back, recapture, recycle or re-manufacture their products at the end of their usable life. For example, the European Union has many product stewardship policies in place to incentivize better product design and full life management such as the Ecodesign directive, WEEE, Product Stewardship and now the circular economy directives.

The key here is that the design of both the products and the business case is created to have full life-cycle responsibility and is managed as an integrated approach to product service delivery so that the product doesn't get lost from the value system. Partnerships between organizations can enable a rapid introduction of product stewardship, such as a bottling company leasing the service of beverage containers to the drinks company. One key element of this is a take-back program, whereby the producing company offers to take back and reconfigure, repair, remanufacture or recycling the products they produced. This incentivizes them to design them to be easily fixed, upgraded or pulled apart for high-value material recycling.

Dematerialization

Reducing the overall size, weight and number of materials incorporated into a design is a simple way of keeping down the environmental impact. As a general rule, more materials result in greater impacts, so it’s important to use fewer types of materials and reduce the overall weight of the ones that you do use without compromising on the quality of the product.

You don’t want to dematerialize to the point where the life of the product is reduced or the value is perceived as being less; you want to find the balance between functional service delivery, longevity, value and optimal material use.

Modularity

Products that can be reconfigured in different ways to adapt to different spaces and uses have an increased ability to function well. Modularity can increase resale value and offer multiple options in one material form. Just like you can build anything with little Lego blocks, modularity as a sustainable design approach implicates the end owner in the design so they can reconfigure the product to fit their changing life needs.

As a design approach for non-physical outcomes, modularity enables creatives to consider how the things they create can be used in different configurations. This is all about making this adaptable to different scenarios and thus increase value over time. It’s important to ensure designs are durable enough to withstand being taken apart and reconfigured, as well as making it easy to do and the style timeless so it increases its duration of use. Modularity should also increase recycling and repairability by offering replacement parts and a service model.

Longevity

Longevity is about creating products that are aesthetically timeless, highly durable and will retain their value over time so people can resell them or pass them on. Products that last longer aren’t replaced as frequently and can be repaired or upgraded during their life as long as their style and functionality have durability as well.

Ensure that the materials you select enable a long life, and be sure to consider multiple use case scenarios such as repair options and resale encouragement.

Disassembly

Design for disassembly requires a product to be designed so that it can be very easily taken apart for recycling at the end of its life. How it is put together, the types of materials that are used and the connection methods all need to be designed to increase the speed and ease of taking it apart for repair, remanufacturing and recycling. Often the case with technology, the norm is to design products that lock the end owner out, discouraging any form of repairability during the use phase while also reducing the likelihood of recapturing the materials at the end of life.

This design strategy is particularly relevant to technology, requiring the design of the sub and primary components to be just as easily disassembled as it is to manufacture them. For maximum recapture, we need to reduce the number of different types of materials, the connection mechanisms, and the ease of extraction. This is a super critical strategy for monitoring technical materials inflow to reduce negative impacts at end of life.

Recyclability

Making a recyclable product goes beyond simply selecting a material that can be so. You have to consider the recyclability of all the materials, the way they are put together and the use case, along with the ease of recycling at end of life. Relying on something being “technically recyclable” as a sustainable design solution to your product is just lazy and often does not result in environmental benefits, as recycling is very much broken. So, you need to ensure that it is being designed to maximize the likelihood that it will be recaptured and recycled in the system it will exist within.

Assembly methods will impact how easily disassembled for recycling products will be. Also, make sure that there are systems in place so that the product can actually be recycled in the location it will end up! For it to be circular, the product has to fit within a closed-loop system, and recycling often is the least beneficial outcome since we lose materials and increase waste through this system.

Connected to disassembly is the ability to easily and cost-effectively recapture the material at end of life. Just making something recyclable does not guarantee that it will be recycled, as it’s often costly and time-consuming. Additionally, many technology items are shredded to get the valuable parts (like gold) instead of getting all the different parts back. What is crucial about this strategy is that it must be used in a system that has the appropriate and functioning recycling market, or a take-back and recapture system must be in place, as well as design features that maximize the behavioral outcomes of the end owners so that the product is actually reacquired and recycled. The Scandinavian bottle recycling system is a perfect example of this. Drink bottles are made of thick and durable materials that can be washed and re-manufactured, and the system is set up with an easy-to-use deposit program and financial incentive to maintain a high level of recapture.

Repairability

Repair is a fundamental aspect of the circular economy. Things wear out, break, get damaged, and need to be designed to allow for easy repair, upgrading, and fixability. Along with the extra parts and instructions on how to do this, we need systems that support, rather than discourage, repair in society. For example, many Apple products are intentionally designed to be difficult to repair, with patented screws and legal implications for opening products up.

Sweden recently opened the world’s first department store dedicated to repair, but any product producer can put mechanisms into place for ease of repair so that the owner has more autonomy over the product and will be encouraged to do so. The Fair Phone is a great example of this.

Reusability

Repair allows the end owner to maintain its value over time, or sell it more easily to then increase its lifespan. But there is also the option of designing so that the product can be reused in a different way from its intended original purpose, without much extra material or energy inputs. An example of this is a condiment jar designed to be used as a water glass.

There are many ways a product can serve a second or even third life after its core original purpose. This approach is useful when you have limited options for designing out disposability.

Re-manufacture

For this strategy, the producer takes into consideration how the parts or entire product can be re-manufactured into new usable goods in a closed-loop system; it’s critical to the technology sector but fits perfectly for many products.

Re-manufacturing is when a product is not completely disassembled and recycled or reused, but instead, some parts are designed to be reused and other parts recycled, depending on what wears out and what maintains its usefulness over time.

Efficiency

During the use phase, many products require constant inputs, such as energy, in the form of charging or water in the form of washing. When a product requires lifetime inputs, it’s called an “active product”, meaning it is constantly tapping into other active systems in order to achieve its function. That’s when design for efficiency comes in, designing to dramatically reduce the input requirements of the product during its use phase.

This will increase the environmental performance and also reduce wear of the product, increasing lifetime use. This approach can also be taken as an overarching one — design to maximize the efficiency of materials, processes, and human labor. As a general rule, “Weight equals impact,” and the more efficient you can be with materials, the lower the overall impact per product unit (this rule has many exceptions, as it is always related to what the alternatives are).

Influence

Things we use influence our lives. This is why social media applications are designed to act like slot machines with continuous scroll, and why airport security lines make you feel like a farm animal. The things we design in turn design us, and thus there is a huge scope for creating products, services, and systems that influence society in more positive ways.

There is still a lot of resistance to sustainability, often because it seems confusing. So, imagine how you can design things that give people an alternative experience to this mainstream perspective. Designing in positive feedback loops to the owner helps change behaviors, just as designing in less options to limit confusion can help direct the more preferable use.

Equity

Accidentally or intentionally, many goods are designed to reinforce stereotypes. Pink toys for girls, dainty watches for women, and chunky glasses for men are a few examples. Reinforcing stereotypes subtly maintains negative and inequitable status quos in society. There are entire labs dedicated to first researching an established trend, and then designing to reinforce it. Design for equity requires the reflection and disruption of the mainstream references that reinforce inequitable access to resources, be it based on gender or outdated stereotypes.

Oppression and inequality exist everywhere, from toilet seat designs to office buildings. Considering the potential impact of your designs on all sorts of humans is critical to creating things that are ethical and equitable. This also applies to the supply chain, ensuring that people along the full chain of materials and manufacturing are valued, paid fairly and respected.

Systems Change

Perhaps the most important of the design strategy tools is the ability to design interventions that actively shift the status quo of an unsustainable or inequitable system. The world is made up of systems, and everything we do will have an impact in some way of the systems around us. So instead of seeing your product as an individual unit, see it as an animated agent in a system, interacting with other agents and thus having impacts.

All systems are dynamic, constantly changing and interconnected. Materials come from nature, and everything we produce will have to return in some way. So, designing from a systems perspective with the objective of intervening will allow for more positively disruptive outcomes to the status quo (see my handbook on the Disruptive Design Method for more on this approach).

Other things to consider

Where is the energy being sourced? Shift from fossil to renewables.

What are the hidden impacts embedded within the supply chain? Remove embodied fossil fuel energy.

How can you recover and put to good use all wasted resources across the supply chain? Look for industrial symbiosis or by-product reuse opportunities.

How can you design in life extension on your products? Design repair and rescue options as a service for your products.

Are there ways of partnering to create industrial symbiosis where your product’s by-products are used as raw materials for another process? Reduce waste to landfill by encouraging secondary industries to use industrial by-products.

How can you design your product to be a service instead? Embrace full product stewardship.

Do you need to produce a product to deliver the functional need? Look for alternative business models to deliver your customer’s functional desires.

What is the energy mix in the manufacturing and use phase? The types of energy used will increase or decrease environmental impacts.

Does a product need to exist or can we deliver value and function in a different format?

The UnSustainable Design Approaches!

There are many insidious techniques used by designers to manipulate and coerce consumers into behaviors and practices that are unsustainable and inequitable. Here are three types you should avoid! There are also many accidental actions that may have good intentions that result in greenwashing, so be careful not to invest more in marketing green credentials than in R&D to ensure your product truly is what you claim it to be.

Design for Obsolescence

Planned obsolescence is one of the critically negative ramifications of the GDP-fueled hyper-consumer economy. This is where things are designed to intentionally break, or the customer is locked out through designs that limit repair or software upgrades that slow down processes. This approach tries to constantly turn a profit by manipulating a usable good so its functionality is restricted or reduced and the customer is forced to constantly purchase new goods. It’s in everything from toothbrushes to technology. The habit has led to massive growth, but at the expense of durability and sustainability. How it is used as a positive strategy is when it is part of a well-designed closed-loop system that enables the product to naturally “die” at the right time so it can be reintegrated into the system it is designed within.

Design for Disposability

Designing for things to break is due to the cultural normalization of disposability as a result of increased use of disposability in the design of everyday goods. From coffee cups to technological items, it is a race to the bottom of our economy, where many reusable things have become hyper-disposable. Single-use items plague our oceans with plastic waste and increase the end cost for small businesses and everyday people, as the more addictive the cycle of disposability is, the more costly it becomes to deliver basic service offerings. I have written extensively about this; read more here.

Dark Patterning

A term coined by designer Harry Brignull, the idea of dark patterns are intentional tricks used by designers to manipulate and lure customers into taking actions they don’t necessarily make the choice to do or may otherwise not agree to. Dark patterning includes often exploiting cognitive weaknesses and biases to get people to do things like purchasing extra items they did not need when checking out online, or creating a sense of urgency to increase purchasing — leveraging single-click buy now for impulse buys, using particular colors to evoke emotions and sharing outright misleading information to increase purchases. This website has many great examples.

LOOKING FOR MORE?

Much of this content is from my handbook on Circular Systems Design, and over at the UnSchool Online, I have a short course on sustainable design strategies and a more extensive one on sustainable design and production. You may also like to find out about the Disruptive Design Method that I created to support deeper design decisions that works to help solve complex problems. I also created the Design Play Cards which include all the eco-design strategies and fun challenges to solve.

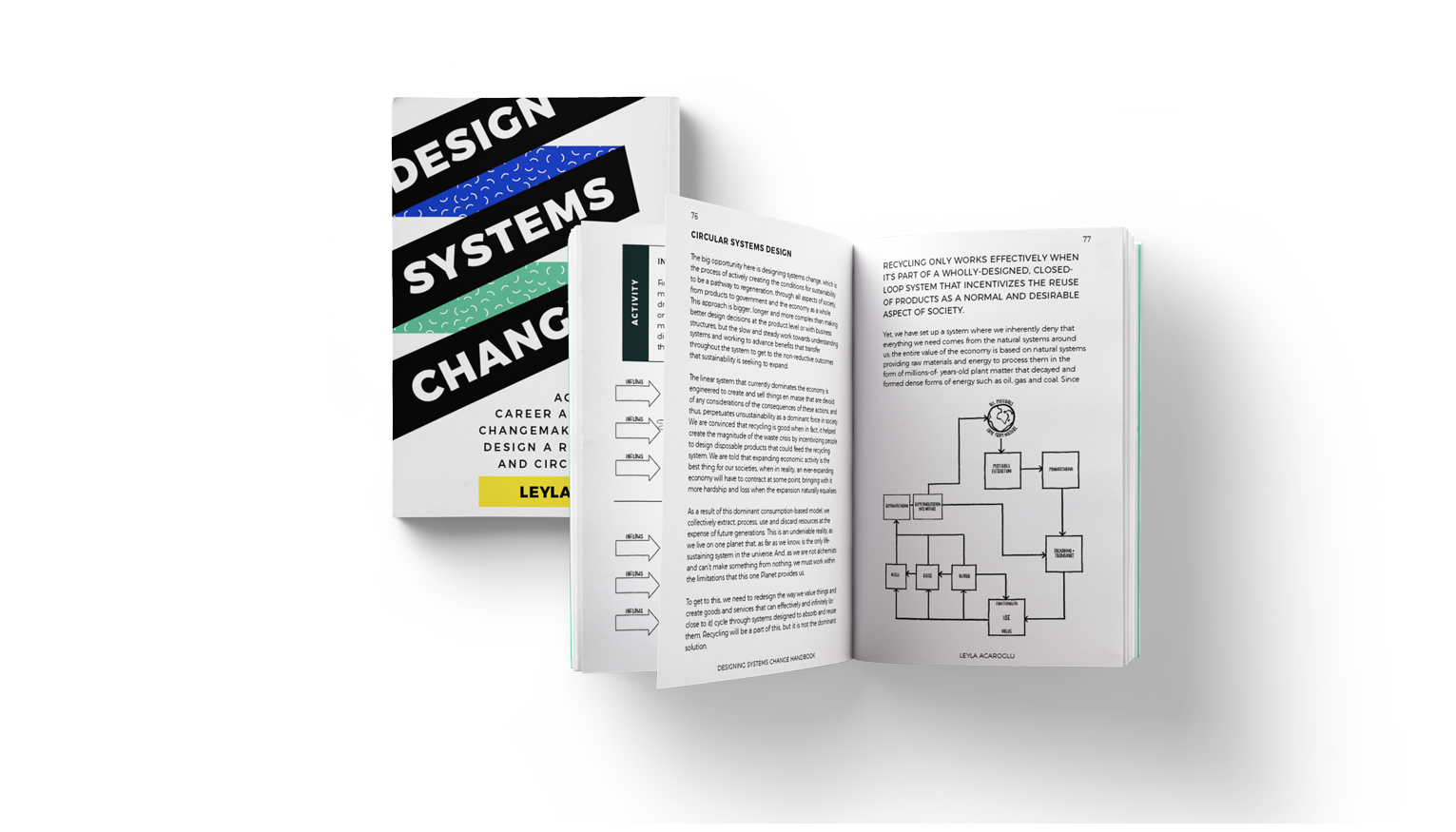

Sneak Peek at the NEW Design Systems Change Handbook by Leyla Acaroglu

Have you read any of our handbooks on making change? Leyla has written one each year since she started the UnSchool in 2014. The series titles include Make Change: A Handbook for Creative Rebels and Change Agents, Tips & Tricks to Facilitating Change, Disruptive Design: A Method for Activating Positive Social Change by Design, Circular Systems Design: A Toolkit for the Circular Economy, and now the fifth one in the series, Design Systems Change: How to activate your career as a creative changemaker and help design a regenerative, circular future.

The new handbook will be released on March 16, 2020 and includes an in-depth exploration of agency-building tools for activating a career of creative changemaking. Packed with new insights and ideas on how to expand your sphere of influence and contribute to the transition to a circular, regenerative future, this handbook is also a workbook, complete with interactive reflections and actions to help expand your capacity to make change.

The new Design Systems Change Handbook is out in March!

In the next few journal articles, we will share excerpts from the upcoming handbook from each of the three main sections (Design, Systems and Change), along with an extensive introduction to Taking Action.

This week, we dive into the introductory section on how to activate your agency by sharing with you one of our favorite parts. If you want to be one of the first to read the full 190+ pages, then you can pre-order it now, and it will be sent to your inbox in a digital format as soon as it's launched on March 16th!

Expert from, Design Systems Change, By Leyla Acaroglu

Introduction

Design is a powerful social influencer that shapes and scripts our experience of the world; we now live in a time where each and every day we interact with a world entirely designed by humans, for humans. Scientists now argue that we have entered into a new geological epoch called the Anthropocene. One of the main drivers of this shift to a world where humans influence every other living thing on the planet is design — the design of technology, of consumer goods, of scientific discoveries, of our lives. Design is everywhere.

The broader concept of design encompasses our planning and intent to dictate and control the way the world works. Humans have been doing this now for eons, but before the Industrial Revolution, where we unlocked the power of fossil fuels, change was confined to the slower changes that nature does organically.

For example, the plants we eat today were adapted each generation by farmers selecting the best-performing ones and changing the way they bear fruit for us; these changes were painstakingly slow. But now we have accelerated the rate of change thanks to technological development, and in doing so, we have greatly accelerated the changes to the systems that sustain life on Earth. We have designed a world exclusively for human needs, and unless we design it better so that we work within the systems that nature provides all that we need to live, then we will end up designing ourselves out of here!

Just as it can accidentally make a mess, design can also be a catalyst for positive and significant change. This is because, at its core, design is about creative problem solving and forming something new that works better than the past version.

Currently, so much of what is created is done so without the understanding of the impacts or the intent to create outcomes that are mutually positive for us and the planet. As a result, we end up living with impacts in which the externalities are ignored and the consequences are often unintended, but nonetheless momentous. So much of what we do in the economy is not accounted for in any way. These are known as externalities, and we often have no idea of how things like pollution are embedded in anything, like a pair of socks or what social costs were paid by the farmers who helped get us our morning coffee. Giant problematic systems like waste and pollution are the products of poorly-designed human systems.

There is no waste in nature; instead, the waste product from one system is the food and fuel for another. Everything is interconnected and optimized to thrive.

It’s obvious to most that we live in a complex and chaotic world with constant technological and social changes. Humans have done an incredible job at creating an array of design and technology solutions to work around the chaos, make our lives more comfortable, increase convenience and ease of living and prolong our lives. Yet many of these designed solutions come with entangled, complicated consequences, most of which are invisible to the human mind.

We consume things ignorant of the impacts their creation causes and are selectively blind to the impacts their subsequent waste will create. Design helps to sell us things that reinforce many of the problems that currently exist. We have created a linear production system with cheap efficient manufacturing where waste is a normal part of our lives now. This is what we need to redesign — the way we meet our needs so that we get beautiful, elegant solutions that are regenerative rather than destructive. We need to design out waste as we know it.

Collectively, we also rely on a linear thought process that fits within a linear world. This system of simplification allows for exploitation as the fundamental components of a successful economy. This is increasingly creating alarming and catastrophic outcomes, allowing us to see how we have designed ourselves into the current status quo, and thus providing a pathway for us to design ourselves out. Design can transcend linear function and provide an interwoven systems approach fundamental to inspiring and enacting change.

Paradoxical to the environmental crises at hand, we live in one of the safest times in all of human history. By many metrics, we are better off as a species now than any generation before us, due to food security, global diplomacy, advances in medicine, mass agriculture and efforts to alleviate poverty.

Yet despite this incredible progress, it comes at a significant cost to the future, as many people now maintain a stressed-out, negative perspective of the world, much of which the media reinforces that society and the planet as a whole are destined for a bleak future. Indeed, our fears will become a reflection of what we do today unless we all work to design a different trajectory.

Ask yourself — if not you, then who?

The future is undefined; it is made up of all our actions today.

And, yes, there are many complex problems at play in the world around us. And, yes, all of these complex problems need creative solutions from skilled people. And, yes, you are one of these people.

Why is it that some will take action, contribute to activating change, question the status quo, be willing to be different and rebel against the things that they know to be wrong, and others will not? Why do some humans passively accept what is and blame others for the things they don’t like?

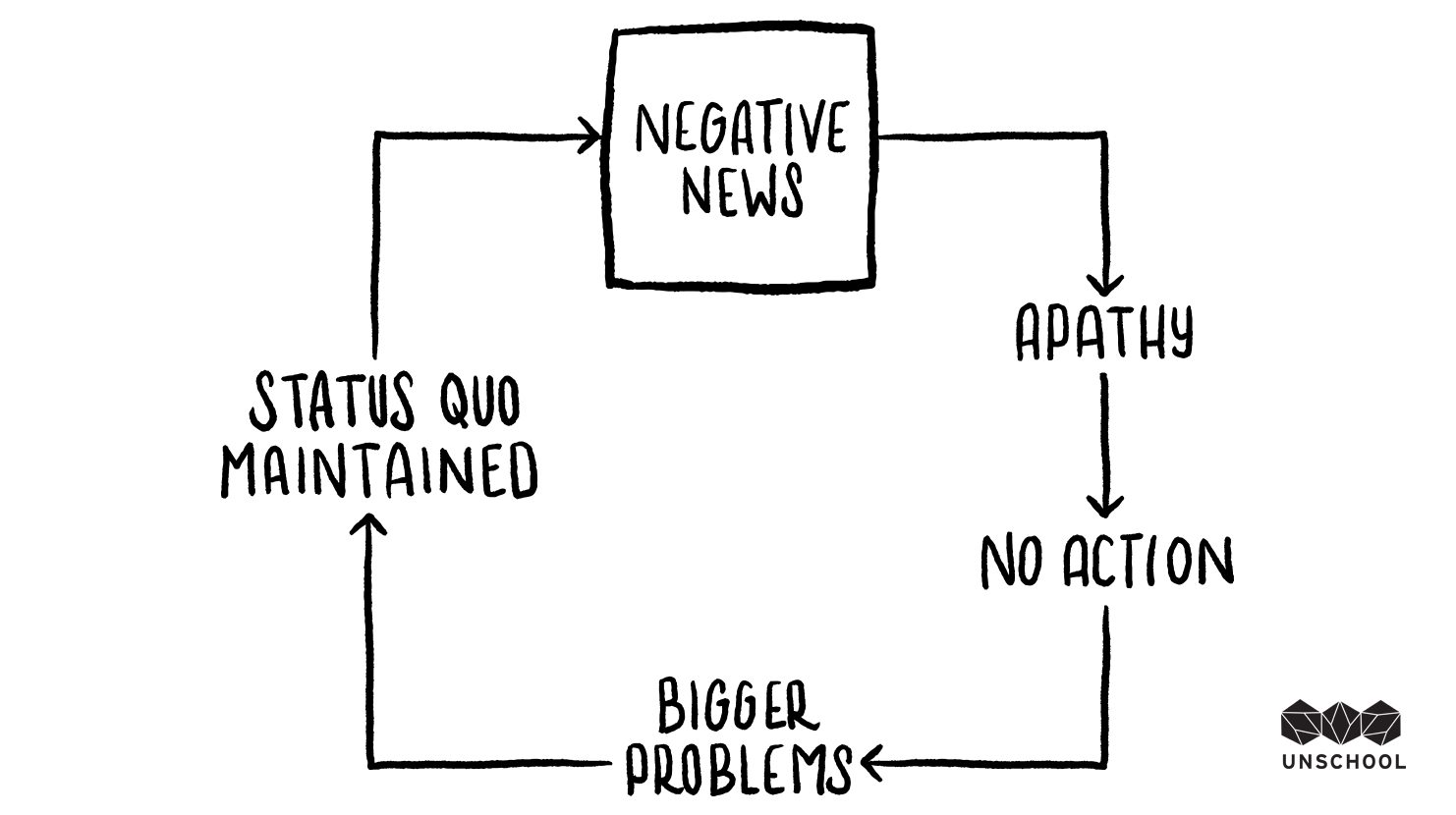

There are many possible answers to these rhetorical questions. One is the cycle of inaction, whereby apathy leads to inaction. But courage, convocation, compassion, curiosity and sheer tenacity are some skills that we can all foster to overcome the apathy and activate our agency to participate in creating a future that overcomes the challenges of the past and ensure that the solutions we put in place today are not the problems of tomorrow.

The Cycle of Inaction

From the climate catastrophe to homelessness, the plastic waste crisis, the opioid epidemic, the Sixth Great Extinction, deforestation, childhood obesity, and the Anthropocene, there are many significant challenges awaiting creative minds to contribute to changing them. We can live in a post-disposable world if we design out waste; we can break the cycle of addiction by creating social systems that enable support. Plastic can play a part in our lives and not pollute the planetary systems if we design higher value products and create closed-loop systems to capture them. These are endless systems change solutions just waiting to be uncovered and emerge new ideas.

The reality and the magnitude of the problems at play can be overwhelming, especially to a mind unequipped with the tools for understanding the systems that create and sustain the problems to begin with. We live in a time of great technological change, where we can get information instantaneously and where that information can be tailored to us very specifically, playing on our fears, convincing us to consume, making it hard to escape the problem cycle.