By Leyla Acaroglu

The Disruptive Design Method (DDM) is a holistic approach to creative problem solving for complex issues. It combines sociological inquiry methods with systems and design thinking approaches. The Method involves a three-phase process of Mining, Landscaping, and Building, and together, these phases create a tactical approach to creative problem solving for positive impact outcomes. In this week’s journal article, I explain the what, why, and how of the DDM, along with ways it can help create non-conventional approaches to complex problems.

The Disruptive Design Method

Design is an incredibly powerful tool that changes the world. Everything around us has been constructed to meet the needs of our advanced human society, and in turn, our individual experiences of the world are influenced dramatically by the designed world we inhabit. We are each citizen designers of the future through the actions we take every day, which is why I developed a systems-based creative intervention design method for exploring and actively participating in the design of a future that works better for us all.

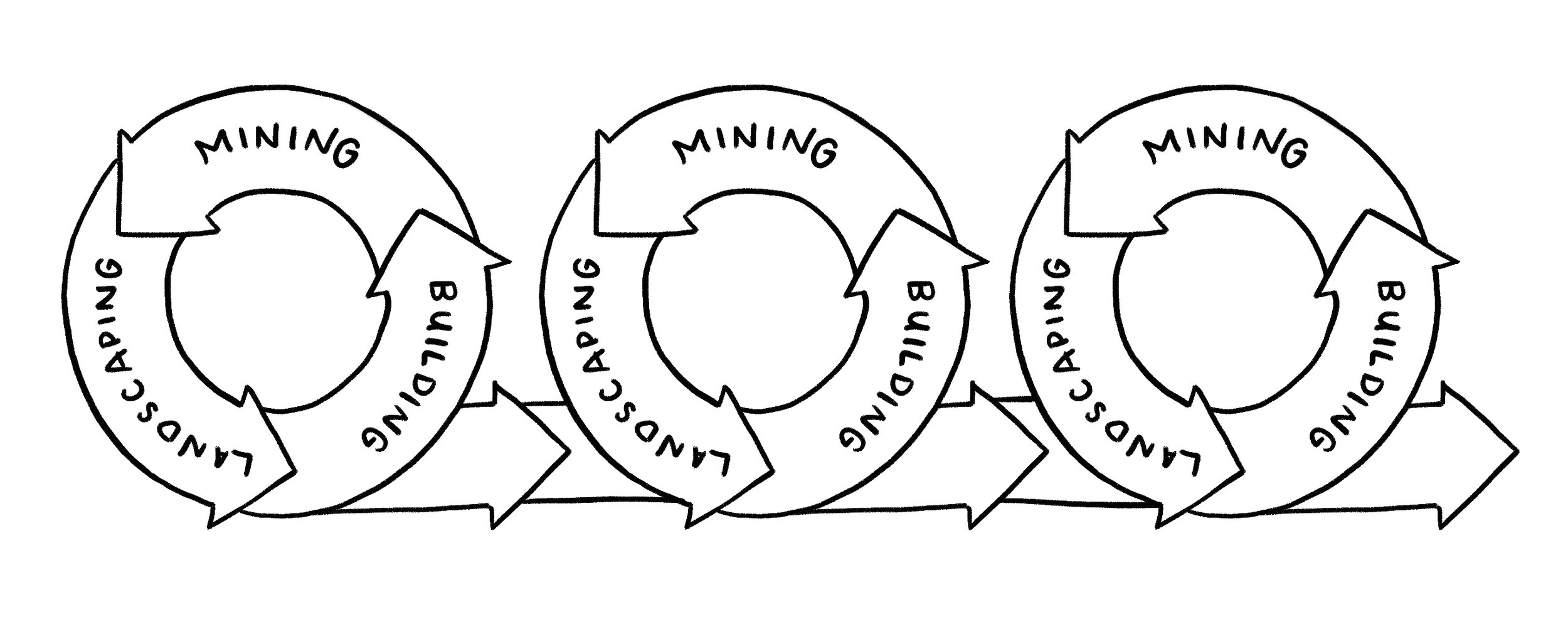

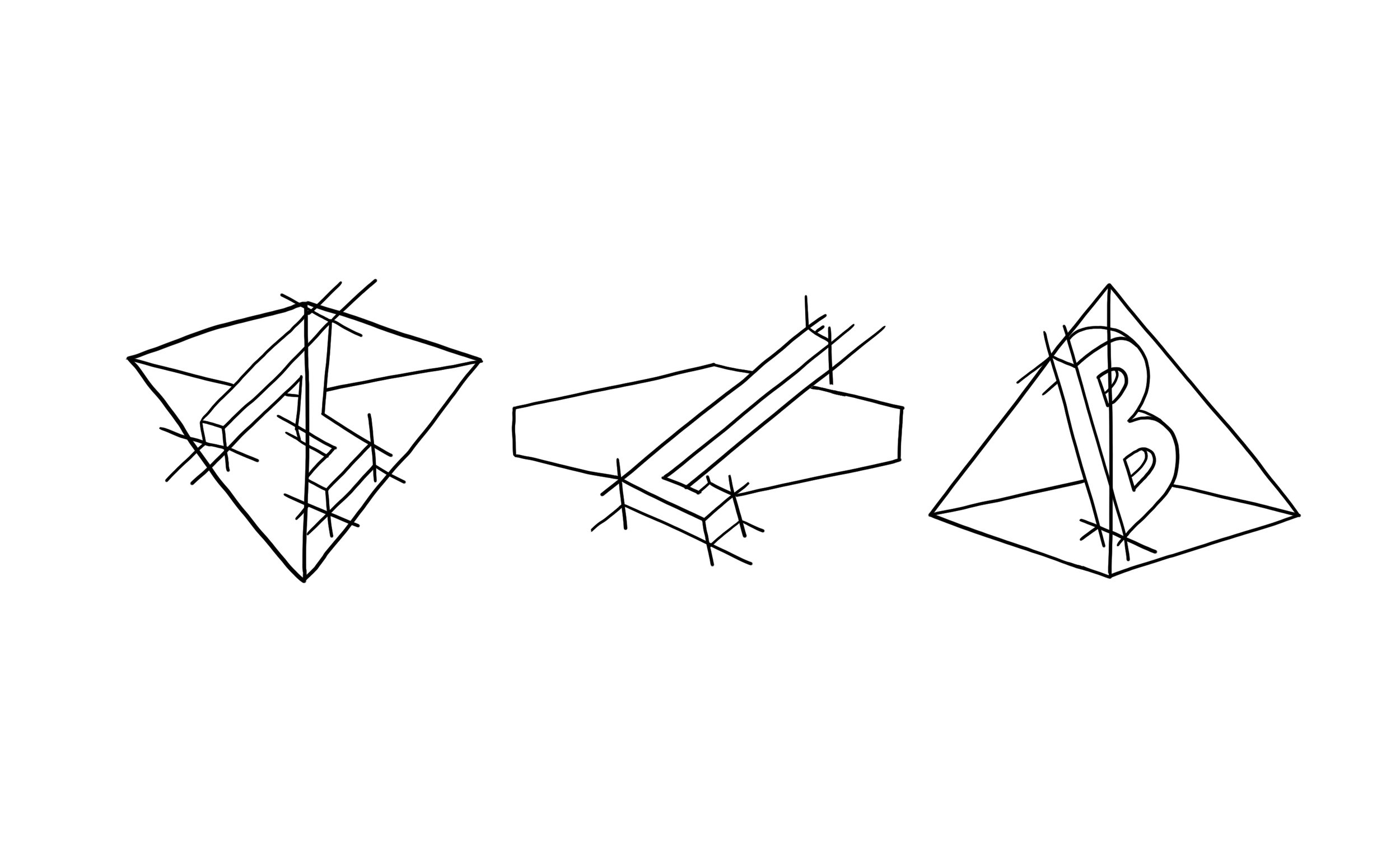

The three-part process of Mining, Landscaping and Building (MLB) is designed to offer a micro-to-macro-and-back-again perspective of the problem arena in which you wish to create positive change within.

The three phases of the Disruptive Design Method: Mining, Landscaping and Building

Created as a way for creatives and non-creatives alike to develop the mental tools needed to activate positive change, the DDM approaches creative problem solving by mining through problems and employing a divergent array of research approaches, moving through to landscaping the systems at play and identifying the connections that reinforce the elements of the system, and then ideating opportunities for systems interventions that amplify positive impact by building new ideas that shift the status quo of the problem. This is then cycled through in an iterative way until the outcome is tangible and effective at altering the state of the issue at hand. As Buckminster Fuller teaches, often the smallest part of the system has the capacity to make the biggest change — and that’s one of the fundamental approaches that the DDM enables: identify the part within the system that you have agency and ability to impact.

The DDM is an iterative process

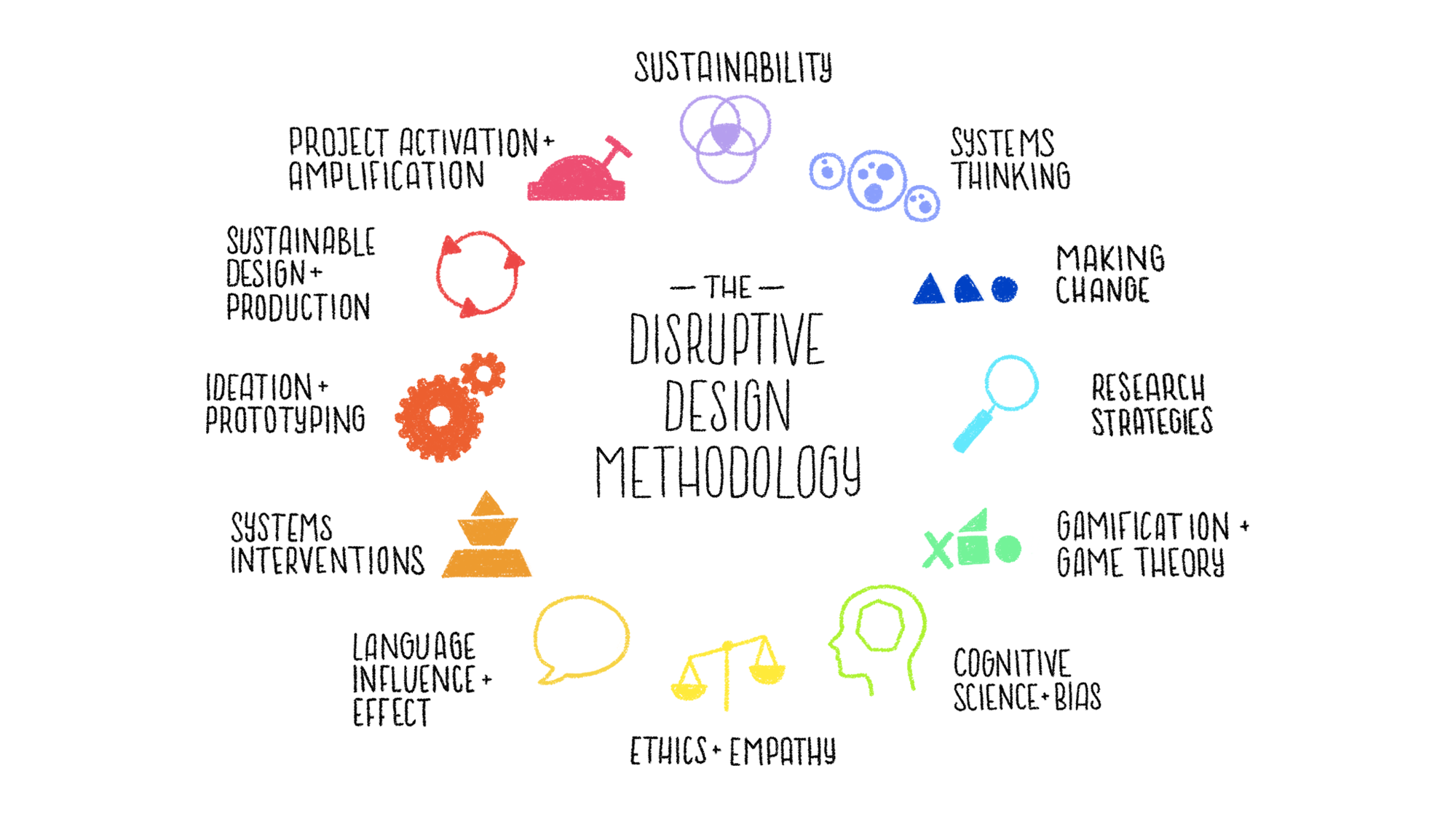

Additionally, the DDM includes a 12-part knowledge set that, when explored as a whole, equips anyone with the thinking and doing tools to be a more aware and intentional agent for change. It also has the tools to cycle through the issues and seek out the non-obvious opportunities, designing divergent solutions that build on your unique individual sphere of influence.

But perhaps most importantly, instead of avoiding or ignoring problems, this method offers up tools for shifting perspectives that enable one to become more of a problem lover with the ability to dive right under the obvious parts of the issue at hand, avoid laying blame, and instead, identify and uncover the parts of the system that reinforce the issue. In a world where many people see and feel problematic impacts with intensity — the social, environmental, and political issues especially — and then become overwhelmed or disabled by the complexity, we see good-intentioned people disengage from taking action. Thus, I can not understate how powerful seeing problems through the lens of opportunity, optimism, and yes, even a bit of love can be for someone. I want to provide an agentizing effect, a set of tools that enable people to move from overwhelming problems to possible actions; after all, the world is made up of the accumulation of individual actions of many, you and me included.

The Origins of the DDM

When I first started to develop the Disruptive Design Method, it was in part a reaction to the one-dimensional problem solving techniques that I had been taught through my years of traditional education. Back in 2014, as I was finishing my PhD and preparing to launch the UnSchool of Disruptive Design, I knew that there needed to be a scaffolding that would support all the content I wanted to fill this experimental knowledge lab with. Drawing on the years of work experience and research I had to date, I went about iteratively developing and refining the modules from 20+ down to 12 core components of the Disruptive Design Methodology set, a learning system that, once fully engaged with, fits together to create the DDM.

The 12 core modals of the Disruptive Design Methodology

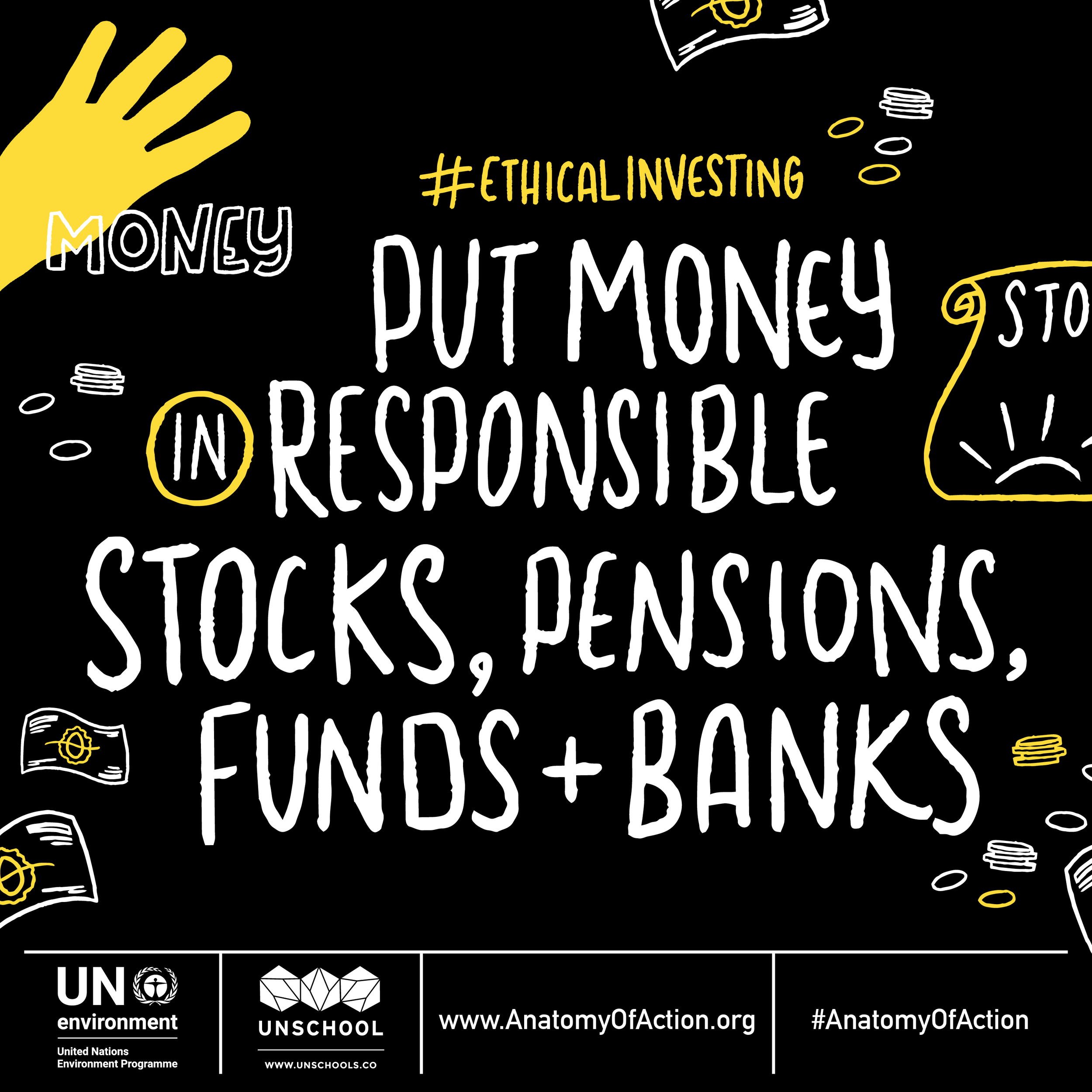

It’s a ‘scaffolding’ because it's not intended to be rigid and formulaic, but instead it is the support that one needs as they start to develop a more three-dimensional view of the world and adopt the skills of systems thinking, problem exploration, and creative intervention design. I personally use this approach in all the commissions and collaborations we do, like in designing learning systems for Finland and Thailand, and in creating sustainable living initiatives, like the Anatomy of Action with the UNEP.

I, along with my team, have taught the DDM and the core approaches of systems and life cycle thinking to thousands of people all over the world, from teenagers to CEOs, with hundreds of alumni completing our in-person programs and thousands enrolled in our online school. We have seen many different incarnations of the DDM and its tools in action throughout our five years of running the UnSchool and its various programs, and this February, we’re adding another option, a live online training course in the DDM.

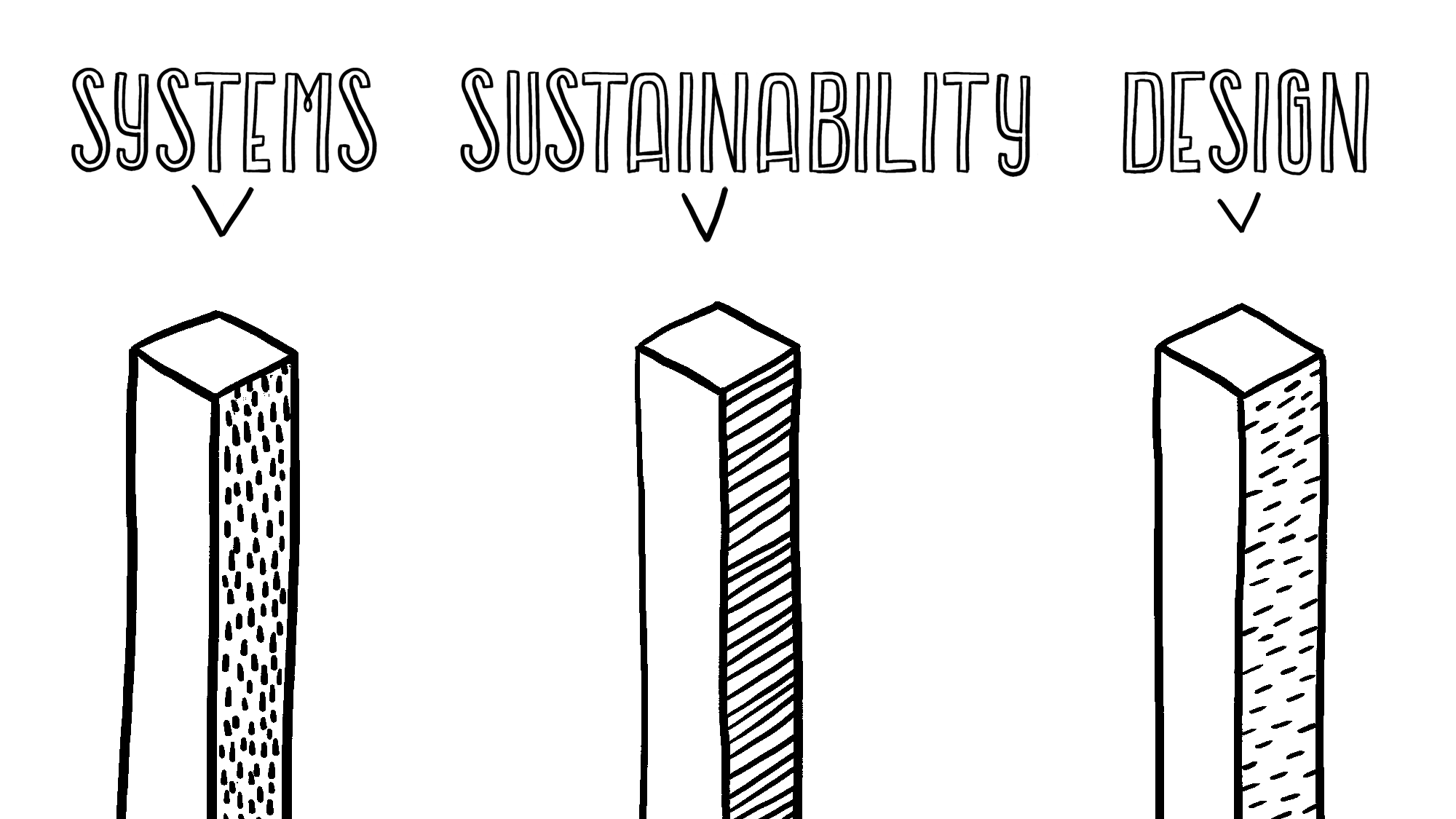

The world needs more pioneers of positively disruptive change — people equipped with the thinking and doing skills that will enable them to understand and love complex systems and then be able to translate that into actual change. There are, of course, many tools and approaches for designing change, and the DDM is just one of a wide suite of tools out there. I am an appreciator of many of them, but for me, the reason why anyone should gain an overview of this approach is that it combines the three pillars of systems, sustainability, and design, of which I have not seen an approach yet to do the same. What this all boils down to is having a unique method on hand to positively intervene and disrupt the status quo of any problem arena to ensure that the outcome is more effective, equitable, circular and sustainable. That’s why we always offer equity access scholarships and ensure that people from all walks of life can gain access to these valuable perspective shifting tools.

Exploring the 3-Parts of Disruptive Design Method

There are three distinct parts of the Disruptive Design Method — Mining, Landscaping, and Building (MLB) — each is enacted and cycled through in order to gain a granulated, refined outcome through iterative feedback loops.

The first part is Mining, where the mindset is one of curiosity and exploration. In this phase, we do deep participatory research, suspend the need to solve, avoid trying to impose order, and embrace the chaos of any complex system we are seeking to understand. The tools of this phase are: research, observation, exploration, curiosity, wonderment, participatory action, questioning, data collection, and insights. This can be described as diving under the iceberg and observing the divergent parts that enable us to understand a problem arena in more detail.

The second stage is Landscaping. This is where we take all the parts that we uncovered during the Mining phase and start to piece them together to form a landscaped view through systems mapping and exploration. Landscaping is the mindset of connection, where you see the world as a giant jigsaw puzzle that you are putting back together and creating a different perspective that enables a bird’s eye view of the problem arena. Insights are gathered, and locations of where to intervene in the system to leverage change are identified. The tools for this phase are: systems mapping (cluster, interconnected circles, etc.), dynamic systems exploration, synthesis, emergence, identification, insight gathering, and intervention identification.

The third part of is Building. This is the creative ideation phase that allows for the development of divergent design ideas that build on potential intervention points to leverage change within the system. The goal is not to solve but to evolve the problem arena you are working within so that the status quo is shifted. Here we use a diversity of ideation and prototyping tools to move through a design process to get to the best-fit outcome for your intervention.

The key to this entire approach is iteration and ‘cycling through’ the stages to get to a refined and ‘best-fit’ outcome. Why do we do this? Because problems are complex, knowledge builds over time, and experience gives us the tools to make change that sticks and grows. This cycling through approach draws upon the Action Research Cycle to create an iterative approach to exploring, understanding, and evolving the problem arena.

The 12-Part Methodology Set

The three applied parts of the MLB Method are based on a more complex Methodology set. This set combines 12 divergent theory arenas to form the foundation of identifying, solving, and evolving complex problems, as well as helps develop a three-dimensional perspective of the way the world works. From cognitive sciences to gamification and systems interventions, the 12 units of the Disruptive Design Methodology are designed to fit together to form the foundations of a practice in creative changemaking.

You can take the full program at your own pace via our online school here, or if you were to do a certification track, you would get access to the full 12 modules, plus loads of extra content on activating and facilitating change. For the live online program taught by me in February 2020, participants will be learning the core approaches and tools, as well as getting live feedback on the application of it in real time. This makes the program perfect for people with real world projects that they want to activate right now.

The Foundation: Systems, Sustainability, and Design

The UnSchool is deeply rooted in a foundation of applied systems, sustainability, and design, forming three knowledge pillars that hold up all we do — including leveraging the Disruptive Design Method. Whenever we teach a program, we always begin with systems thinking as the foundation, as it is one of the most powerful tools that we can use address complex problems. It enables any practitioner to see how everything is interconnected, and systems can be viewed from multiple perspectives, allowing a shift from rigid to flexible mindsets. We also engage with the principles of sustainability through each phase, which for us, means doing more with less, understanding how the planet works so that we can work within its means, and evolving from an extraction-based society to a circular and regenerative one.

Through the Mining phase, systems boundaries are used to define the problem arenas that one wants to explore. Through systems mapping, research techniques, observation and reflection, all the parts that make up a system and their connections are explored through the landscaping phase, laying the groundwork for exposing unique places to intervene (which is often not where you would intuitively think, based on your starting knowledge in the problem arena).

From this, new knowledge is built from the Mining and Landscaping phases, which forms the foundation for the Building phase — rapidly designing divergent and creative ideas to intervening in the problem arena. Any problem from small, hyper-local concerns to massive global issues can be explored and evolved through this MLB Method. And, because it’s equally a thinking and doing practice, it can be adapted and evolved based on any problem. The core of the approach is always systems, sustainability, and design.

Activating change

At the UnSchool, we approach making change as a state of being; we believe that being change-centric is a way of defining a life agenda, finding purpose, and setting the tone for how you live and contribute through your life and work. We all have the power to affect positive social and environmental change in and through everything we do, from the things we buy to the conversations we have and the kind of work we do. This change-centric approach is by all means a cultivated one in which you have to work at wanting to make change. Because truly, it’s not always easy; in fact, trying to make change can definitely hurt sometimes — and frankly, it often requires some measure of failure along the way. How would we have evolved as a species had we not experienced millions of years of failure and accidents? Allowing the space for failing early on creates better, stronger results later. In saying this, it should also be noted that change is one of the easiest things to make happen... if you have the right tools and resources, which are built into the DDM.

What you will learn from taking a Disruptive Design Workshop

LOVING THE PROBLEM

Many people avoid problems, which means that they never truly understand them. By learning to love problems and see them as opportunities in disguise, you will develop an open mind that thinks differently. This is all about being curious and trying to understand something before you attempt to solve it! The more curiosity you can foster, the more things you will uncover about the world around you.

SEEING RELATIONSHIPS

Everything is interconnected, and actions create reactions. Being able to see the relationships that make up cause and effect are part of any good problem solvers tool belt. The content of the DDM is designed to foster systems perspectives as well as deep identification with cause and effect relationships.

PERSPECTIVE SHIFTING

The ability to see the world through other people's eyes is critical to building resilience, empathy, and leadership skills. We will uncover how to constantly reflect and explore the world from diverse perspectives, overcome biases and be able to put yourself in the shoes of others to understand why people think or behave differently to you based on their own life and learning experiences.

COLLABORATION

Respectfully and successfully working with others, despite differences, is critical to creativity and leadership skills. The goal is to encourage people to see that diversity in collaboration is just as important as agreement, and that coming to a consensus can be achieved in many different ways. Many of the tools we teach, such as systems mapping can be used as brilliant collaboration tools, so you gain incredible opportunities to foster effective collaboration.

Held online over 4 weeks in Feb 2020, with 2 classes per week, we have designed this small group live online training program to ensure you can fit this into your regular life and maximize your learning experience. This live online training is perfect for anyone wanting to gain valuable insights into activating systems change through the Disruptive Design Method, as well as learning tools of problem loving, circular systems design, systems interventions, and creative problem solving.