By Leyla Acaroglu

At the UnSchool, we have three core pillars that make up the foundation of all that we do: systems, sustainability, and design. The systems component is the ability to see the world for its dynamic, interconnected, interdependent, and constantly changing set of relationships that make up the complex whole. I recently shared just why systems thinking is such a powerful tool for effecting change, but a concept stuck in theory does little for the greater good. Understanding that everything is interconnected and being able to apply this knowledge as a tool for effecting change are two different things, and what’s most important is the practical experience plus the applied tools to turn theories into action. To move from ideas in the brain to practice in the real world, it helps to be equipped with the distilled and applicable knowledge about which tools can be used and how to apply these in ways that achieve the desired outcome — in our case, this is always positive social and environmental change. We have developed many simple applied systems tools, such as the systems mapping approaches, and to get you started on thinking in systems, let’s dive into the foundations of systems thinking!

How we See the World

The status quo of how we are all taught is to think in linear and often reductionist ways. We learn to break the world down into manageable chunks and see issues in isolation of their systemic roots. This dominant way of approaching the world is a product of industrialized educational norms – in one way or another, we have learned, through our 15 to 20+ years of mainstream education, and/or through socialization, that the most effective way to solve a problem is to treat the symptoms, not the causes.

Yet, when we look at the world through a systems lens, we see that everything is interconnected, and problems are connected to many other elements within dynamic systems. If we just treat one symptom, the flow-on effects lead to burden shifting and often unintended consequences. Not only does systems thinking oppose the mainstream reductionist view, but it also replaces it with expansionism, or the view that everything is part of a larger whole and that the connections between all elements are critical. Being able to identify relationships over obvious parts, seeking to decipher the dynamics of these relationships, and then being able to interpret the underlying models that created the relationships is the foundation of thinking in systems.

The Iceberg Model

Learning to Name and Define Systems

If you had to, what words would you use to define a system? Funnily enough, many important systems are easily identified by the word ‘system’ after them, such as respiratory, education, legal or mechanical systems. Systems are absolutely everywhere, of all manners, shapes, and sizes; from the intricate workings of your body (nervous, neurological, digestive, cardiovascular etc) to the infinite possibilities of space, our world is made up of interconnected and interdependent systems. We interact with many of these which helps us understand them intuitively, but so often is the case that we are unable to identify a system that is not obvious to us — like many of the indirect natural systems that keep us alive. This can explain a lot about how we have created so many of the environmental issues we face today!

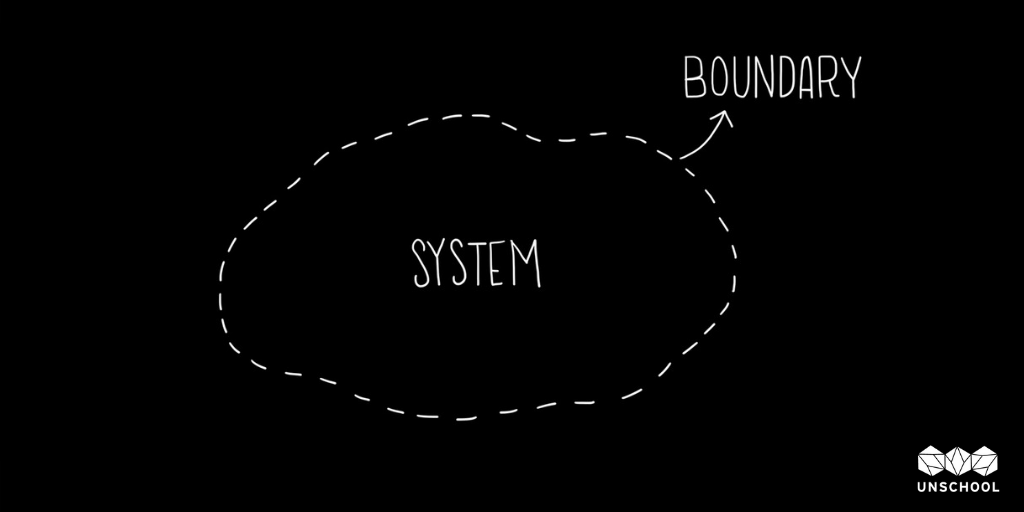

A simple way to define a system is it will: be dynamic (constantly changing), be evolving (having emergent properties), and have a boundary (a definable limit to its internal components and processes). Systems are essentially networks made up of nodes or agents that are linked in varied and diverse ways. By using systems thinking, we identify and understand these relationships as part of the exploration of the larger systems at play. Everything is interconnected, every system is made up of many subsystems (of which even smaller systems make these up too), and then these are also all part of much larger systems. Just as we are made up of atoms with molecules and quantum particles, problems are made up of problems within problems! Every system is like a Matryoshka doll, made up of smaller and smaller parts within a larger whole. Seeing things in this way helps to create a more flexible view of the world and the way it works, and it illuminates opportunities for addressing some of its existing and evolving problem arenas. When teaching systems thinking, I like to explain this as the ability to look through a microscope at the tiny world that makes up all matter, as well as being able to shift to the telescope and see the infinite possibilities of space and the universe. In between these two opposite perspectives, you get a more three-dimensional perspective of how the world works.

Three Key Systems at Play

Although the world is made up of endless large and small interconnected systems, I define three key systems that make up the fundamental relationships between humans, the things we create, and our reliance on nature. These are the social systems, which are the intangible human-created relationships and culturally governing aspects such as education, government, and legal systems; the industrial systems, which include the physical infrastructure of roads, buildings, manufacturing systems, and products that allow us to function as a society and meet our human needs, and the natural systems that are the ecosystem services which allow for the other two systems to sustain themselves, providing all the resources for humans to survive and all the raw materials for our industrial needs. These three major systems keep the economy churning along, the world functioning for us humans, and our society operating in order (sort of, anyway!). This is, of course, a very anthropocentric point of view, one I define in order to enable people to see the deep reliance and misalignment we have with the natural systems at play. Whenever I run a workshop and we create a map of these, people often get stuck on naming all the ecosystems, but have no problem identifying social and industrial systems that they interact and rely on.

The fascinating thing is that the social systems are the rules and structures that make up our societies — the things that we humans have created to manage ourselves — and thus, can be reconfigured within generations. They are the often unspoken rules that maintain societal norms, rituals, and behaviors, all of which reinforce the unsustainability that we have created for ourselves. The same applies to the industrial systems — they are the outcome of our collective desires for speed, access, convenience, connectivity, success, status, cleanliness, and all manners of human desires and needs. The manufactured world is just that: created, and intentionally designed to facilitate the ever-expanding suite of human needs. However, the biggest and most important system of all, the ecosystem, cannot be redesigned or restricted without it impacting all the rest, yet we treat all natural services as though they are infinite and degradable. But clean air, food, fresh water, minerals, and natural resources need to be respected and shared with all species for the collective success of the planet.

6 Key Tools for Systems Thinking

Words have power, and in systems thinking, we use some very specific words that intentionally define a different set of actions to mainstream thinking. Words like ‘synthesis,’ ‘emergence,’ ‘interconnectedness,’ and ‘feedback loops’ can be overwhelming for some people. Since they have very specific meanings in relation to systems, allow me to start off with the exploration of six* key themes.

*There are way more than six, but I picked the most important ones that you definitely need to know. To dive deeper, check out my 'Tools for Systems Thinkers’ series on Medium.

1. Interconnectedness

Systems thinking requires a shift in mindset, away from linear to circular. The fundamental principle of this shift is that everything is interconnected. We talk about interconnectedness not in a spiritual way, but in a biological sciences way.

Essentially, everything is reliant upon something else for survival. Humans need food, air, and water to sustain our bodies, and trees need carbon dioxide and sunlight to thrive. Everything needs something else, often a complex array of other things, to survive. Inanimate objects are also reliant on other things: a chair needs a tree to grow to provide its wood, and a cell phone needs electricity distribution to power it. So, when we say ‘everything is interconnected’ from a systems thinking perspective, we are defining a fundamental principle of life. From this, we can shift the way we see the world, from a linear, structured “mechanical worldview’ to a dynamic, chaotic, interconnected array of relationships and feedback loops. A systems thinker uses this mindset to untangle and work within the complexity of life on Earth.

2. Synthesis

In general, synthesis refers to the combining of two or more things to create something new. When it comes to systems thinking, the goal is synthesis, as opposed to analysis, which is the dissection of complexity into manageable components. Analysis fits into the mechanical and reductionist worldview, where the world is broken down into parts.

But all systems are dynamic and often complex; thus, we need a more holistic approach to understanding phenomena. Synthesis is about understanding the whole and the parts at the same time, along with the relationships and the connections that make up the dynamics of the whole.

Essentially, synthesis is the ability to see interconnectedness.

3. Emergence

From a systems perspective, we know that larger things emerge from smaller parts: emergence is the natural outcome of things coming together. In the most abstract sense, emergence describes the universal concept of how life emerges from individual biological elements in diverse and unique ways. Emergence is the outcome of the synergies of the parts; it is about non-linearity and self-organization and we often use the term ‘emergence’ to describe the outcome of things interacting together.

A simple example of emergence is a snowflake. It forms out of environmental factors and biological elements. When the temperature is right, freezing water particles form in beautiful fractal patterns around a single molecule of matter, such as a speck of pollution, a spore, or even dead skin cells. Conceptually, people often find emergence a bit tricky to get their head around, but when you get it, your brain starts to form emergent outcomes from the disparate and often odd things you encounter in the world.

There is nothing in a caterpillar that tells you it will be a butterfly — R. Buckminster Fuller

4. Feedback Loops

Since everything is interconnected, there are constant feedback loops and flows between elements of a system. We can observe, understand, and intervene in feedback loops once we understand their type and dynamics.

The two main types of feedback loops are reinforcing and balancing. What can be confusing is a reinforcing feedback loop is not usually a good thing. This happens when elements in a system reinforce more of the same, such as population growth or algae growing exponentially in a pond. In reinforcing loops, an abundance of one element can continually refine itself, which often leads to it taking over.

A balancing feedback loop, however, is where elements within the system balance things out. Nature basically got this down to a tee with the predator/prey situation — but if you take out too much of one animal from an ecosystem, the next thing you know, you have a population explosion of another, which is the other type of feedback — reinforcing.

5. Causality

Understanding feedback loops is about gaining perspective of causality: how one thing results in another thing in a dynamic and constantly evolving system (all systems are dynamic and constantly changing in some way; that is the essence of life).

Cause and effect are pretty common concepts in many professions and life in general — parents try to teach this type of critical life lesson to their young ones, and I’m sure you can remember a recent time you were at the mercy of an impact from an unintentional action. Causality as a concept in systems thinking is really about being able to decipher the way things influence each other in a system. Understanding causality leads to a deeper perspective on agency, feedback loops, connections, and relationships, which are all fundamental parts of systems mapping.

6. Systems Mapping

Systems mapping is one of the key tools of the systems thinker. There are many ways to map, from analog cluster mapping to complex digital feedback analysis. However, the fundamental principles and practices of systems mapping are universal. Identify and map the elements of ‘things’ within a system to understand how they interconnect, relate, and act in a complex system, and from here, unique insights and discoveries can be used to develop interventions, shifts, or policy decisions that will dramatically change the system in the most effective way.

Although this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to systems thinking, the key takeaway is that ultimately, approaching life from a systems perspective is about tackling big, messy, real world problems rather than isolating cause and effect down to a single point. In the latter case, “solutions” are often just band-aids that may cause unintended consequences, as opposed to real and holistic systemic solutions. Looking for the links and relationships within the bigger picture helps identify the systemic causes and lends itself to innovative, more holistic ideas and solutions, for a more sustainable future that works better for us all.

——————————————————

If you are ready to dive deeper into the world of systems thinking, then you should take our Systems Thinking course online, or if you are a bit more advanced, then continue to leverage that knowledge in learning to design systems interventions in this course.

You can also explore the Circular Classroom, which is a free, multilingual educational resource accessible to anyone but designed specifically for students and teachers alike to integrate circular thinking into high school and upper secondary classrooms, all packaged up in a fun, beautiful format. It offers the opportunity to think differently about how we design products, how the economy works, how we meet our needs as humans, and how to support the development of more creative professional roles that help to design a future that is about social, economic, and environmental benefits — and of course, this all begins with a systems mindset.

I explain in detail how to do many applied systems thinking practices in my Circular Systems Design handbook, and we run in-person programs at the UnSchool that equip people to become applied systems thinkers for enacting positive change in the world.